The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The Return of Anthony Comstock, Part 2: The Comeback Trail

Things have turned around for Anthony Comstock of late. The old anti-smut crusader, who defined the role of the professional censor, and whose obsessions blotted out the law of free speech for more than 40 years beginning in the 1870s, was all but forgotten by the mid-twentieth century. Now, however, more than a century after his death, a bumper crop of books have appeared attesting to the old crusader's pivotal role in the history of freedom of speech and women's rights.

Amy Werbel's 2018 book Lust on Trial meticulously detailed Comstock's rise and fall, with a particular emphasis on art history, and concludes "the story of Comstock's efforts undeniably calls into question the efficacy of trying to control morality and sexuality by statute and prosecution." In fact, the magnitude of Comstock's influence may best be measured by the strength of the opposition he created.

By setting himself up as the Bond villain of censorship, he forced writers, artists, feminists, and free thinkers to devise better arguments supporting freedom of speech at a time before courts had caught on. Werbel observes that, ironically, "Comstock can be credited almost single-handedly with instigating the foundations of a First Amendment Bar."

Drawing on Werbel's work, novelist Annalee Newitz featured Comstock as the central antagonist in her 2019 book The Future of Another Timeline, about time-traveling feminists who do battle with "Comstockers"—as well as the old moralist himself—in 1893 (and various other times). Their quest is to prevent a Handmaid's Tale-type future from being engineered by travelers inspired by Comstock.

The historical research Newitz conducted for her book was repurposed for a September 2019 New York Times op-ed piece in which she dubbed Comstock "the original anti-feminist crusader." She warned "[h]is name may be forgotten, but the age of Comstockery is not over." Comstock's tactics—"a combination of media manipulation and ruthless legal strategies—are a precursor to those used by anti-feminists on social media and in Washington today."

Another Comstock biography, Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women, dropped in mid-summer 2021, and it makes the case Comstock was "one of the most important men in the lives of nineteenth-century women" because of his crusades against contraceptives and abortion. Sohn details Comstock's crusades against "sex radicals"—those who openly advocated sexual liberation of women, access to contraceptives and abortion, and information about sexual health—and concludes the "sex radicals' legacy lies in their use of speech to fight the repression of speech."

Sohn expressly rejects "victim-oriented feminism," which she describes as "limited, inciting phobia and panic, turning sex into something that is only ugly, only dark, only violent." "Victim-oriented feminism," she writes, "robs women of their strength and robs the movement of the diversity that made way for the sex radicals." Her conception of free speech is as broad as Comstock's was narrow, and she observes that for the sex radicals, "[t]o oppose the Comstock laws was to oppose all restrictions on speech."

This was followed closely by Brett Gary's Dirty Works: Obscenity on Trial in America's First Sexual Revolution. The main focus of Gary's book is the pioneering work of ACLU attorney Morris Ernst and his free speech battles from the 1920s through the 1950s. However, in his opening chapter Gary makes clear those struggles were largely necessary to push back against the work of Comstock, whom he describes as "the most effective propagandist warning about the dangers of obscene materials," and "the nation's foremost censor and smut eradicator."

Ernst himself had a long and distinguished career that began after Comstock's death, but as Gary observes, "the key enemy was always Anthony Comstock, and the anti-intellectual, anti-modern, anti-sexual attitudes compressed into the label 'Comstockery.'" These retrograde attitudes had a "long life in the nation's laws, undergirding federal and state censorship policies and activities well into the 1950s and beyond." And Gary concludes that Comstock's influence has not vanished, and that "aspects of 'Comstockery's' patriarchal and restrictive impulses toward women remain powerful in the culture, especially in reproductive politics."

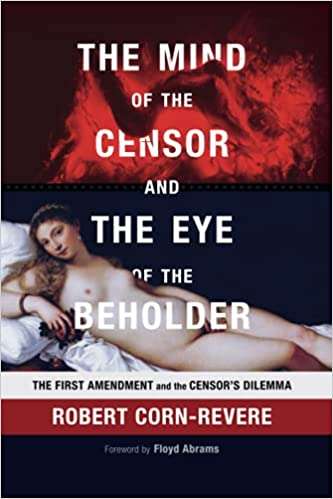

My own book, The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder—The First Amendment and the Censor's Dilemma, is not a Comstock book per se, but devotes several chapters to Comstock's career and his role in defining what it means to be a morals crusader (or, as in current parlance, an "activist"). This occupation is not limited to either side of the political spectrum, and The Mind of the Censor describes how Comstock's methods continue to be used by advocates of all political persuasions against what they see as "speech crimes." By institutionalizing censorship as an entrepreneurial endeavor, Comstock set the tone and tactics of anti-speech activists to this day.

Half a century after Comstock's death, long after his name faded from the limelight, the editor of a re-issue of one of his books described Comstock as "the beau ideal of the American reformer" and "the spiritual father of today's youthful suburbanites who have undertaken to cleanse newsstands and drugstore magazine racks of 'objectionable' material." That observation from the 1960s is even more true in the context of some of today's battles over freedom of speech.

To be sure, none of these recent books paints Comstock in a sympathetic light. Indeed, none have a single good thing to say about him. But no matter; the renewed attention means Comstock is back in the game. More importantly, as these books make clear, Comstock largely defined the game.

[This post is based on the new book, The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder: The First Amendment and the Censor's Dilemma.]

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

It’s important to remember that half a century ago, the Supreme Court upheld the Civil Rights Laws as simple morality laws, exactly like the sorts of laws Anthony Comstock advocated. They said so.

And the more direct parallel is that their opponents were absolutely certain that the only possible reason anyone could have for such laws is simple anomosoty towards Southerners. People simply hate Southerners and want to destroy them.

If the zeitgeist had gone differently, would there have been a biography of Martin Luther King called The Man Who Hates Southerners?

Even more fundamentally, John Calhoun said exactly the same thing about slavery. He talked aboug the earlier 19th century’s morality-mongers and their per issue of the day in almost exactly the same terms Corn-Revere describes Comstock. It was simply obvious to hhim that hatred was the motivator, that their couldn’t possibly be anything else behind abolitionists.

If Corn-Revere is right about Comstock, this makes it much more plausible that Calhoun was right about slavery. After all, many of the same moral-mongers who opposed slavery joined Comstock’s bandwagon once reconstruction hit. It was often the very same people. If their primary motivation was hate, as Corn-Revere claims, maybe Calhoun was also right about them.

On the other hand, if Calhoun’s characterization was wrong - if being too zealous in the Southerners’ cause inhibited him from making rational judgements about his opponents’ motivations - perhaps Corn-Revere’s judgment might have a similar problem.

After all, Calhoun and Corn Revere are not only making the same judgment. It is making them about the same people. And these people used the same justification - morality - to describe their own justification for opposing both what Calhoun supported and what Corn-Revere supports.

Perhaps they weren’t lying and their motives for both really were the same. If morality is hatred, Calhoun was right, the 13th Amendment was animosity legislation, and people ought to admit it. But if morality concerns aren’t really a form of hatred, Corn-Revere is also wrong and he should admit it.

"But if morality concerns aren’t really a form of hatred, Corn-Revere is also wrong and he should admit it."

Could if be not hatred but rather a mix of insularity, ignorance, and lack of character that drives Comstock and his like? Perhaps the censoring, scolding goobers are so twisted that they believe they "love" the "sinners?"

"the Supreme Court upheld the Civil Rights Laws as simple morality laws"

Yes.

"exactly like the sorts of laws Anthony Comstock advocated."

No, the opposite. Civil rights laws were liberal and morally right, as well as rational; Comstock's proposals were illiberal and morally wrong, as well as batshit insane and ill-conceived even accepting Comstock's premises.

That's all the difference in the world, and entirely destroys the rest of your argument.

Feminists have been campaigning to ban pornography (including things like Playboy magazine!) for decades.

(Of course, their few "successes" were overturned by the courts.)

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/20/us/pornography-ban-in-indiana-is-upset-as-unconstitutional.html

I didn’t make this argument. But the fact that many of the people opposed to pornography throughout US history were women (and many still are) does tend to cast a certain amount of doubt on the claim that it’s all about hatred of women.

The fact that many not only were women, not described themselves as feminists, but actually characterized pornographers as anti-women, also tends to suggest that things are not quite so open and shut as all that.

Here's some mews you can use: half the population is women. The fact that many ANYTHING were women is as meaningless as saying many drank water or ate bread.

When the claim is “supporters of Comstock were motivated by hatred of women,” the fact that many of Comstock’s supporters WERE women is relevant.

It’s not conclusive. Maybe they were self-haters. But it’s relevant.

We’ll take this a step further. The close resemblance of the critique of opposition to abortion as hatred of women to Calhoun’s critique of slavery as hatred of slaveholders suggest an analogy in the other direction. Would today’s feminists who make these sort of arguments have opposed slavery if they had been around in Calhoun’s day? After all slavery alleviates the drudgery of housework and frees women to pursue other things in the absence of modern machinery; it serves the same function.

It’s arguably essential to the liberation of women in the pre-machine age, it comes in at least as handy as abortion does.

Would the same people who are today convinced that anything opposed to their interests is necessarily based on hate really have thought differently about something similarly opposed to their interests back then? The fact that people like Professor Corn-Revere have no compunction about recycling Calhoun’s rhetoric frankly suggests otherwise.

After all, the other arguments for slavery were remarkably similar to the ones for abortion today. Science proves (Origin of Species came out in 1854 and was quickly adopted for the purpose) that only fully developed humans are fully human. Less developed humans, those who come earlier on the development path may superficially look human, but really aren’t, something more akin to apes.

Calhoun was, after all, very progressive. He joined the Unitarian Church because it was a progressive church free of superstitious, encumbering beliefs (like opposition to slavery). He made exactly the same argument our own Rev. Arthur Kirkland regularly makes, and that Professor Corn-Revere seems to be making, that he moralists opposed X because they hate those who rely on it, and because they support superstition and oppose science and progress.

Shouldn’t the fact that exactly this argument was deployed in favor of slavery at least give people who readily make the same argument regarding their preferred causes some pause?

If you’re right, why wasn’t Calhoun right? If Calhoun was wrong, why aren’t you?

It is, after all, exactly the same argument.

It isn't even close to the exact same argument unless you leave out the different bits.

It is the same. It wasn’t so long ago that, for example, wnvironmentalists were being castigated as opposed to science and progress. Eugenicists used this argument to castigate their opponents. And so on.

It isn’t so easy to use science to make what are essentially moral claims. Scientists have regularly ended up on the losing side. The eugenicists had some of the best scientists of the day boosting them. Slaveholders exploited the theory of evolution for their ends as soon as it came out. And most scientists were firmly on the side of industry and treated environmentalists as anti-progress until fairly recently. And so on.

This the basis of my argument that courts should return to rational basis jurisprudence on these matters. It isn’t so easy, in the middle of things, to see who’s right and who’s wrong. It seems obvious. But our subjective sense of certainty is often illusion.

I think I kind of understand your point if it's to say that it's generally unhelpful to assume the motivations of those we disagree with. I mean, other than as a political tactic to win over people who care about that more than they might care about the underlying merit of the person's argument.

Is that what you're saying?

I am making two separate points. One is that, as you say, it’s better not to castigate the motives of ones political opponents but focus instead on the merits. People can be well-motivated but still wrong. As I point out, many of Comstock’s supporters had been abolitionists when that was fhe issue of the day.

The second is that no political group has a monopoly on truth. Religious people have sometimes been wrong, scientists have sometimes been wrong (and science misused when applied to political ends). Everybody has sometimes been wrong in our history.

At the same time, everybody has sometimes been right. The religious right was right about slavery, it was right about eugenics. Thst means you have to treat them with a little bit of respect, even though they might well be wrong about other things. A narrative that one side has always been the good people and the other side always the bad people may help whip up the base. But it isn’t really true.

My final point is you often can’t really know who’s right and who’s wrong when in the middle of things, even though everyone has a strong opinion and is certain of their positions. A century or so later things may seem very different. That’s why I think that absent a specific warrant in the Constitution, courts should generally not take sides on many of these issues but leave them to the legislative process, where people muddle through and try to get at the truth and what’s best as best they can.