The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Lakefront and the Origins of the American Public Trust Doctrine

A new book begins by explaining the real origin story of the American public trust doctrine.

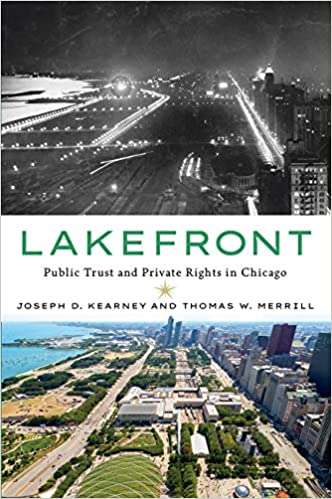

Resources in the United States are generally held as private property, which gives the owner the right to exclude others. There is one glaring anomaly: certain resources are subject to a "public trust," prohibiting the authorization of private exclusion rights. Where did this doctrine come from, and how has it played out over time? We explore this issue in depth in our new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press). We are most grateful for the opportunity, as guest-bloggers this week, to present some highlights from the book or reflections based on it.

Resources in the United States are generally held as private property, which gives the owner the right to exclude others. There is one glaring anomaly: certain resources are subject to a "public trust," prohibiting the authorization of private exclusion rights. Where did this doctrine come from, and how has it played out over time? We explore this issue in depth in our new book, Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago (Cornell University Press). We are most grateful for the opportunity, as guest-bloggers this week, to present some highlights from the book or reflections based on it.

The public trust doctrine's conventional origin story goes something like this: In 1869, a corrupt Illinois legislature granted 1,000 acres of submerged land in Lake Michigan, east of downtown Chicago, to the Illinois Central Railroad, including the right to build a new outer harbor in the lake. Four years later, a new legislature, voted in by an outraged citizenry in the midst of the Granger Movement, repealed this "Lake Front Steal." The U.S. Supreme Court, in a landmark decision in 1892, upheld the repeal, on the ground that the submerged land under a body of navigable water is held in trust for all the people, to ensure they always and forever have access to such waters.

The Court's decision became a model for various states to recognize this "trust" in certain resources that are "inherently public" (Professor Carol Rose's helpful term from 1986). The doctrine functions as a kind of anti-privatization rule: although most resources are subject to a right to exclude, public trust resources come with an inalienable right of the general public not to be excluded. Unsurprisingly, the public trust doctrine has become a favorite of environmentalists and other activists who would like to see public control extended over a variety of resources, ranging from wilderness areas to wildlife, cyberspace, and the climate or atmosphere itself.

Lakefront's in-depth research into the origin story and the monumental 1892 decision reveals a couple of surprising points. One is that the Illinois Central's 1869 manipulation of the state legislature was triggered by a change in the law: a most surprising 180-degree turn in property rights. Up to about 1860, the conventional view, following the common law of England, had been that the bed of Lake Michigan, like other submerged land in Illinois, was owned by whoever happened to be the riparian owner of the land bordering the water.

After 1860, the view shifted—not yet authoritatively but perceptibly—toward the State of Illinois as the owner of the bed of Lake Michigan. Since the state at that time had no capacity to develop this newly discovered right, a variety of machinations broke out to secure a grant from the legislature, transferring the rights to some private or local-government group. This was deeply threatening to the Illinois Central, which over a decade and a half (beginning in 1852) had made very significant investments in railroad and terminal facilities on landfill in the lake. So, having survived threats in the 1867 legislative session, the railroad in 1869 basically out-hustled, with some bribery likely involved, rival groups to secure a grant of the land for itself. The railroad's motivation, in other words, was largely defensive.

The second point concerns the odd fact that nearly twenty years passed between the repeal of the grant to the railroad (1873) and the Supreme Court decision upholding the repeal under the public trust doctrine—and even a decade between the repeal and the beginning of the lawsuit in 1883. The basic reason for this was that the Illinois Central had been convinced by its lawyers that the repeal was unconstitutional. After all, the Supreme Court had held in Fletcher v. Peck in 1810 that a completed grant of land by a state legislature is protected against repeal by the Contract Clause of the Constitution—even in the face of plausible allegations that the original grant was corrupt. The Court in its post-Civil War incarnation had reaffirmed this principle of vested rights. So the Illinois Central refused to compromise with the city of Chicago over whether the railroad had the right to construct an outer harbor protecting (and augmenting) its facilities along the lakefront.

When the issue finally reached the Supreme Court, the vote was close: 4 to 3. There were two recusals, one by a stockholder in the railroad (Justice Samuel M. Blatchford) and the other by Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller, who had represented the city against the railroad in the lower court—and who, apparently unbeknownst to all save (presumably) him, had been a principal in one of the earlier (1867) schemes to obtain a grant of the submerged land for a group of private investors. The dissenters, led by the newly appointed Justice George Shiras Jr., agreed with the railroad that the repeal was unconstitutional under established doctrine.

The majority opinion, by senior-most Justice Stephen J. Field, adopted the public trust idea, scarcely mentioned or developed in the litigation, and construed it as a principle embedded in the state's title—you will recall this title to have been only recently and not yet authoritatively recognized—to the land under Lake Michigan. Field's opinion resonates with his Jacksonian-Democrat suspicion of government grants creating monopoly franchises—hence the language in the opinion disapproving of the grant to a corporation favored by other generous government land grants and created for purposes other than constructing a harbor.

To obtain a fourth vote, Field needed Justice John Marshall Harlan, who had decided the case as circuit justice in the court below on the theory that the grant could be construed as conveying only a revocable license. Accordingly (we conjecture), Field tossed in a long paragraph describing the Harlan theory, without expressly endorsing it.

In short, by the narrowest possible margin, the public trust doctrine joined the police power as an exception to the vested-rights principle of the Contract Clause. The accumulating exceptions would contribute to the gradual demise of the once-powerful Contract Clause and the rise of substantive due process during the same era. Very soon after the Illinois Central decision, the Court decided that the public trust doctrine was a matter of state law, not federal constitutional law. So the doctrine gradually developed a number of variations in different states, which limited its visibility, but also opened it up to a variety of creative extensions.

Our next post will explore some of the ambiguities that emerged with the original public trust doctrine—for example, who the trustee is, who has standing to enforce it, and what resources are covered by the trust.

Show Comments (9)