The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

11th Circuit Divides About Whether Design of Palm Beach Mansion is Protected by the First Amendment

We "affirm on the First Amendment claim because there was no great likelihood that some sort of message would be understood by those who viewed Burns's new beachfront mansion"

Yesterday, a divided 11th Circuit panel decided Burns v.Town of Palm Beach. This case presented an ongoing issue at the intersection of property law and constitutional law: is architectural design protected by the First Amendment.

Judge Luck's majority opinion summarizes the facts:

Donald Burns wants to knock down his "traditional" beachfront mansion and build a new one, almost twice its size, in the midcentury modern style. The new mansion, Burns says, will reflect his evolved philosophy of simplicity in lifestyle and living with an emphasis on fewer personal possessions. The new two-story mansion will have a basement garage, outdoor pool and spa, cabana, and exercise room.

To build his new mansion, Burns had to get the approval of the Town of Palm Beach's architectural review commission. . . .

Applying its criteria, the architectural review commission denied Burns's building permit. The commission found that his new mansion was not in harmony with the proposed developments on land in the general area and was excessively dissimilar to other homes within 200 feet in terms of its architecture, arrangement, mass, and size.

Burns sued the town, claiming that the criteria the commission used to deny his building permit violated his First Amendment free speech rights and his Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protection.

Here is a photograph of Burns's current 10,063 square foot mansion.

But in 2013, Burns decided he wanted to knock down the "traditional home" so he could build a new mansion in the midcentury modern style to convey the evolution of his personal philosophy. He wanted his new mansion "to be a means of communication and expression of the person inside: Me." He picked a design of international or midcentury modern architecture because it emphasized simple lines, minimal decorative elements, and open spaces built of solid, quality materials. According to Burns, the midcentury modern design communicated that the new home was clean, fresh, independent, and modern—a reflection of his evolved philosophy of simplicity in lifestyle and living with an emphasis on fewer personal possessions. It also communicated Burns's message that he was unique and different from his neighbors.

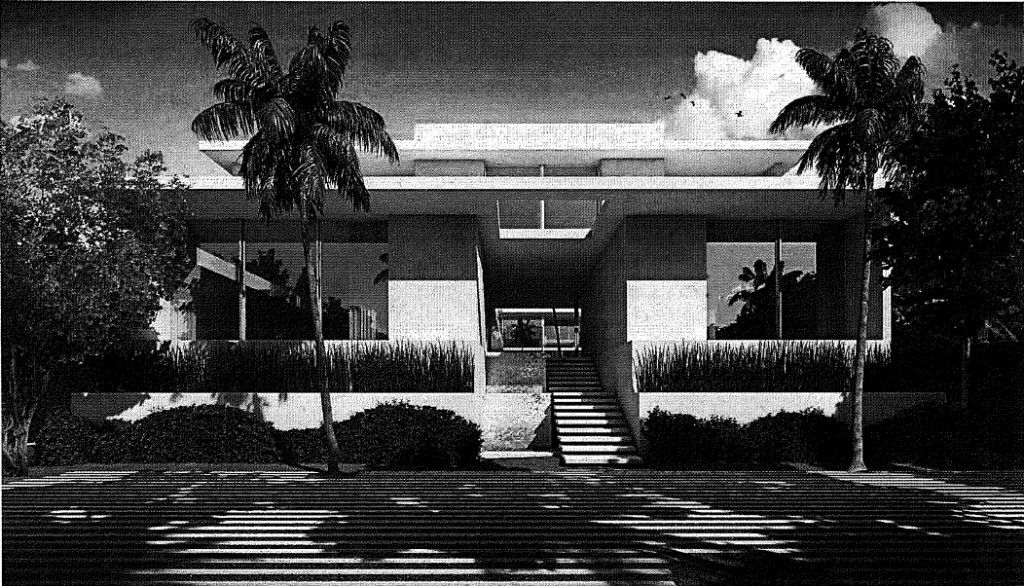

And here is the revised plan:

Burns initially submitted a plan to the town council that proposed demolishing his existing 10,063 square foot mansion and building in its place a 25,198 square foot mansion in the midcentury modern design. His emphasis on fewer personal possessions included two stories and a basement containing a five-car garage, wine storage area, and steam room. The first floor would have an open-air entry, guest rooms, dining room, kitchen, family room, powder rooms, and living room. The open-air entry would lead to the pool, spa, and cabana. The second floor would have more guest rooms, an exercise room, and the master bedroom.

The majority found that Burns's design was not protected by the First Amendment, nor were the Town's criteria unconstitutionally vague:

We conclude that summary judgment was not granted too early and affirm on the First Amendment claim because there was no great likelihood that some sort of message would be understood by those who viewed Burns's new beachfront mansion. We also affirm the summary judgment on the Fourteenth Amendment claims because the commission's criteria were not unconstitutionally vague and Burns has not presented evidence that the commission applied its criteria differently for him than for other similarly situated mansion-builders

The dissent disagreed:

In my view, the First Amendment -- the most powerful commitment to think, speak, and express in the history of the world -- does not permit the government to impose its majoritarian aesthetic whims on Burns without a substantial reason. The First Amendment's protection of the freedom of speech is not limited to the polite exchange of words or pamphlets. It is not limited -- as the majority suggests -- to public displays clearly related to the narrow issues of the day. It protects art, like architecture, and it protects artistic expression in a person's home as powerfully as in the public sphere, if not more so.

The majority and dissent even squabbled about the nature of the architectural review commission:

Judge Marcus writes:

The question in this case is whether a government commission created by the Town of Palm Beach with the Orwellian moniker "ARCOM" may prevent Burns from expressing his philosophy and taste through the architecture of his home and create a work of art on land he owns solely because a majority of the members of the Commission do not like the way it looks

The majority responds.

The dissenting opinion uses the name "ARCOM" for the architectural review commission and then calls the name it uses "Orwellian." Dissenting Op. at 72. If by Orwellian the dissenting opinion means any government agency that administers regulations impacting our lives, then the architectural review commission is as Orwellian as the state board of therapeutic massage, the local dog catcher, and every one of the alphabet soup of departments and agencies and bureaus in Washington, D.C.

Yes, Orwellian. All of the above.

This case should be included in property law casebooks.

Show Comments (33)