The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Lawyers: Happier but More Prone to Alcohol Abuse Than We Thought?

The National Health Interview Survey finds that lawyers are less likely to exhibit mental illness than the general population but are more likely to abuse alcohol than similarly educated peers. [UPDATE: This is Yair Listokin & Ray Noonan's post, but I inadvertently failed to include their bylines at first -- sorry about that.]

In our last post, we explained how previous ad hoc studies of lawyer mental health are flawed and how the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the "trusted gold standard" of public health data, measures prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse more accurately. In this post and our article, we explore what the NHIS sample tells us about lawyers' mental health and alcohol abuse.

Mental Health

The NHIS measures mental health with the Kessler 6 screening scale (K6). The K6 score has been extensively validated as a reliable indicator of acute mental illness. Participants are asked six questions about their mental health, and their responses to each question are given a value from zero to four and then summed. A total K6 score equal to or above five indicates that the respondent is suffering from moderate or serious mental illness, while a K6 score equal to or above 13 indicates serious mental illness. Here, "serious mental illness" means meeting the criteria for a DSM-IV disorder (other than a substance use disorder) within the last year and suffering serious impairment (defined using the Global Assessment of Functioning scale). Those with moderate mental illness do not meet the criteria for a DSM-IV disorder but report other worrisome characteristics, such as life impairment and increased visits to a mental health care professional.

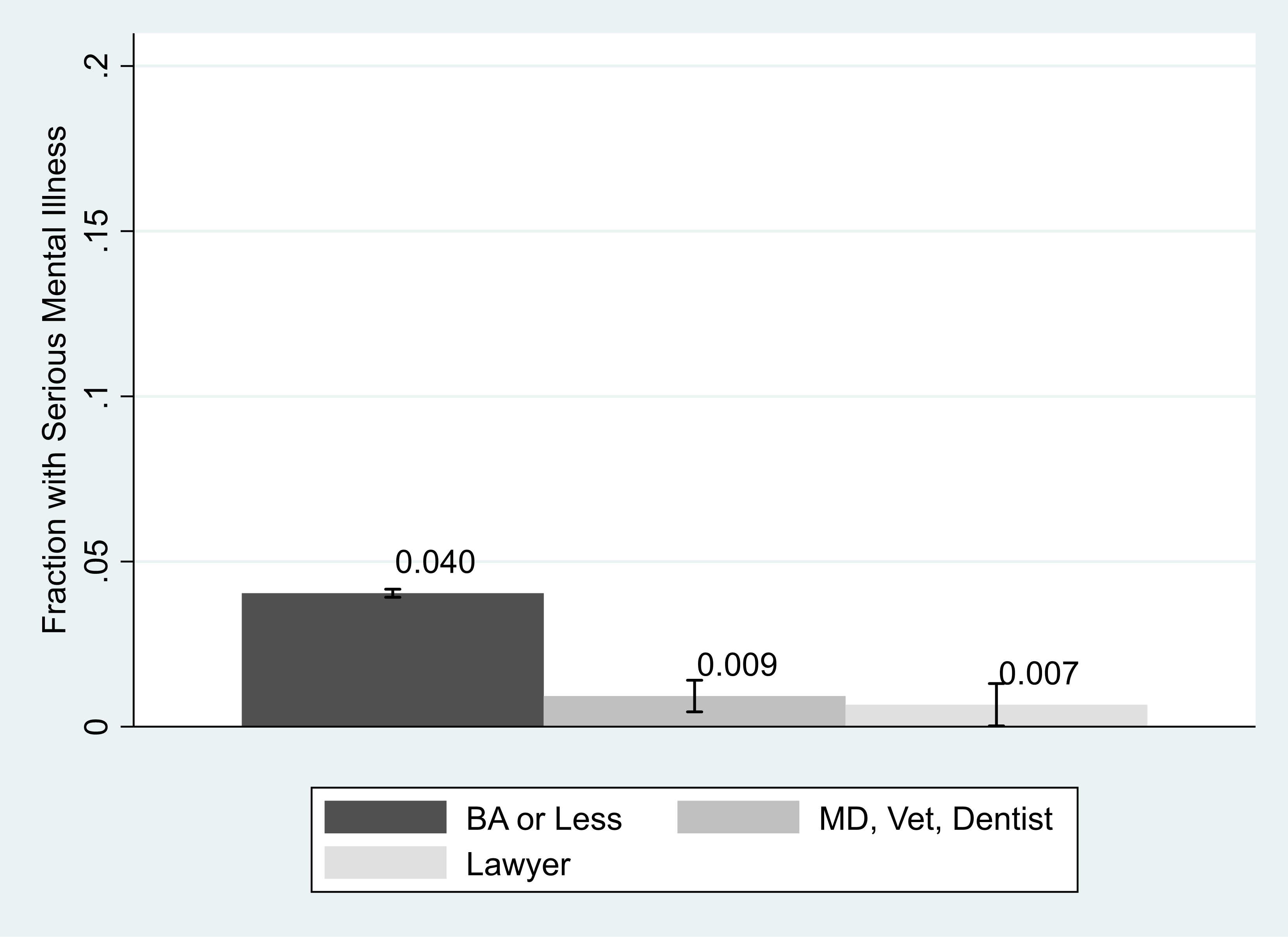

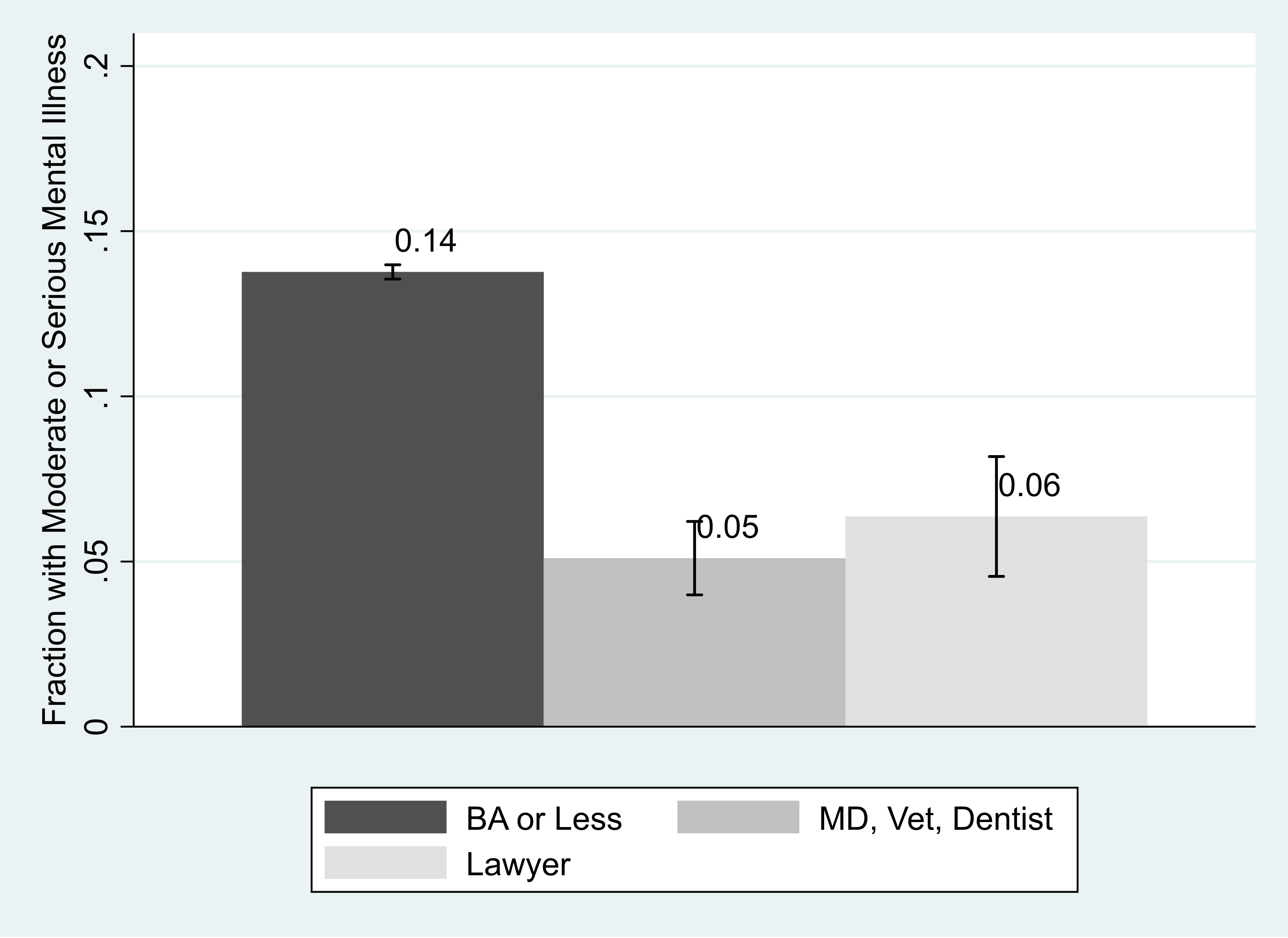

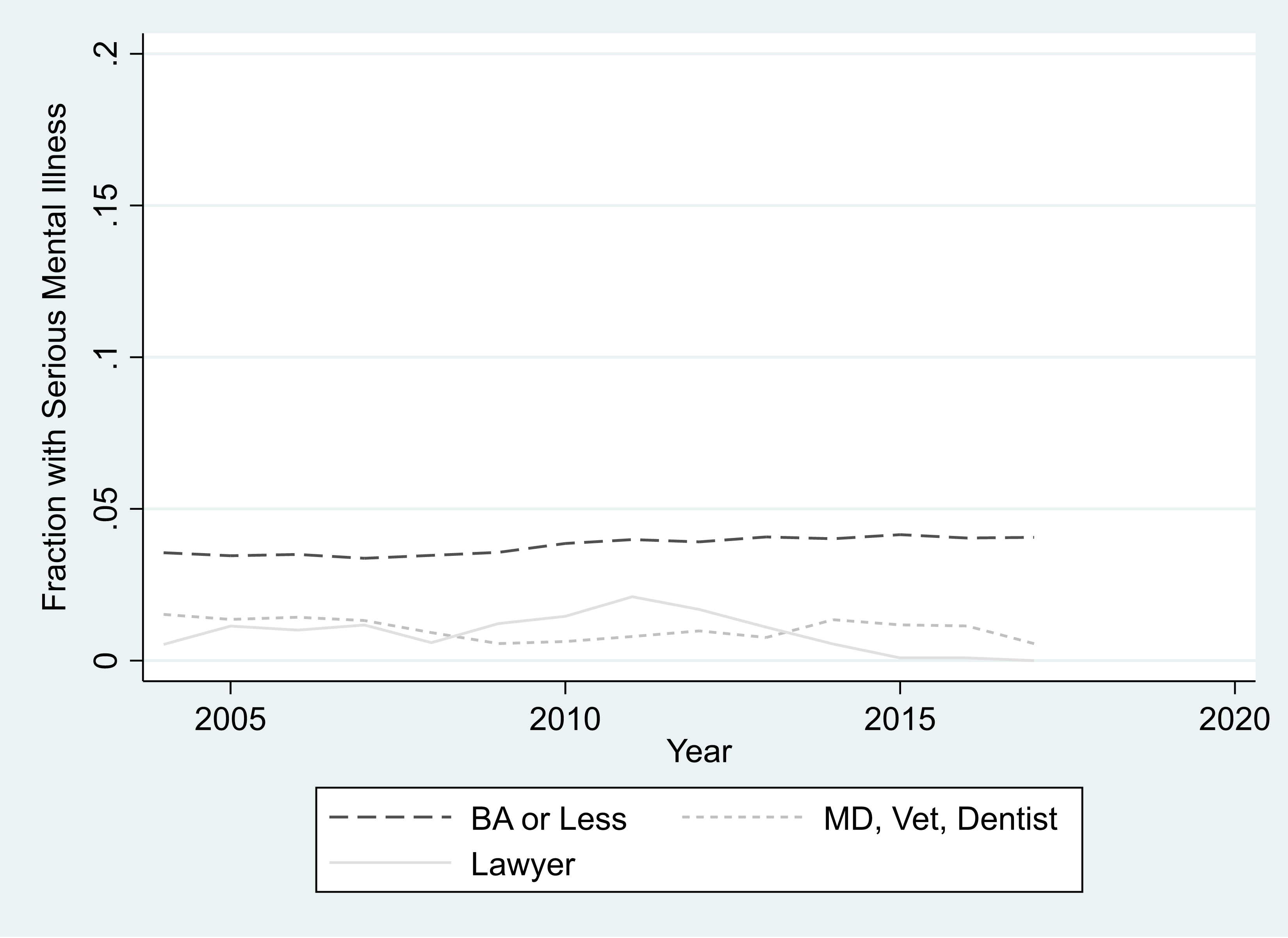

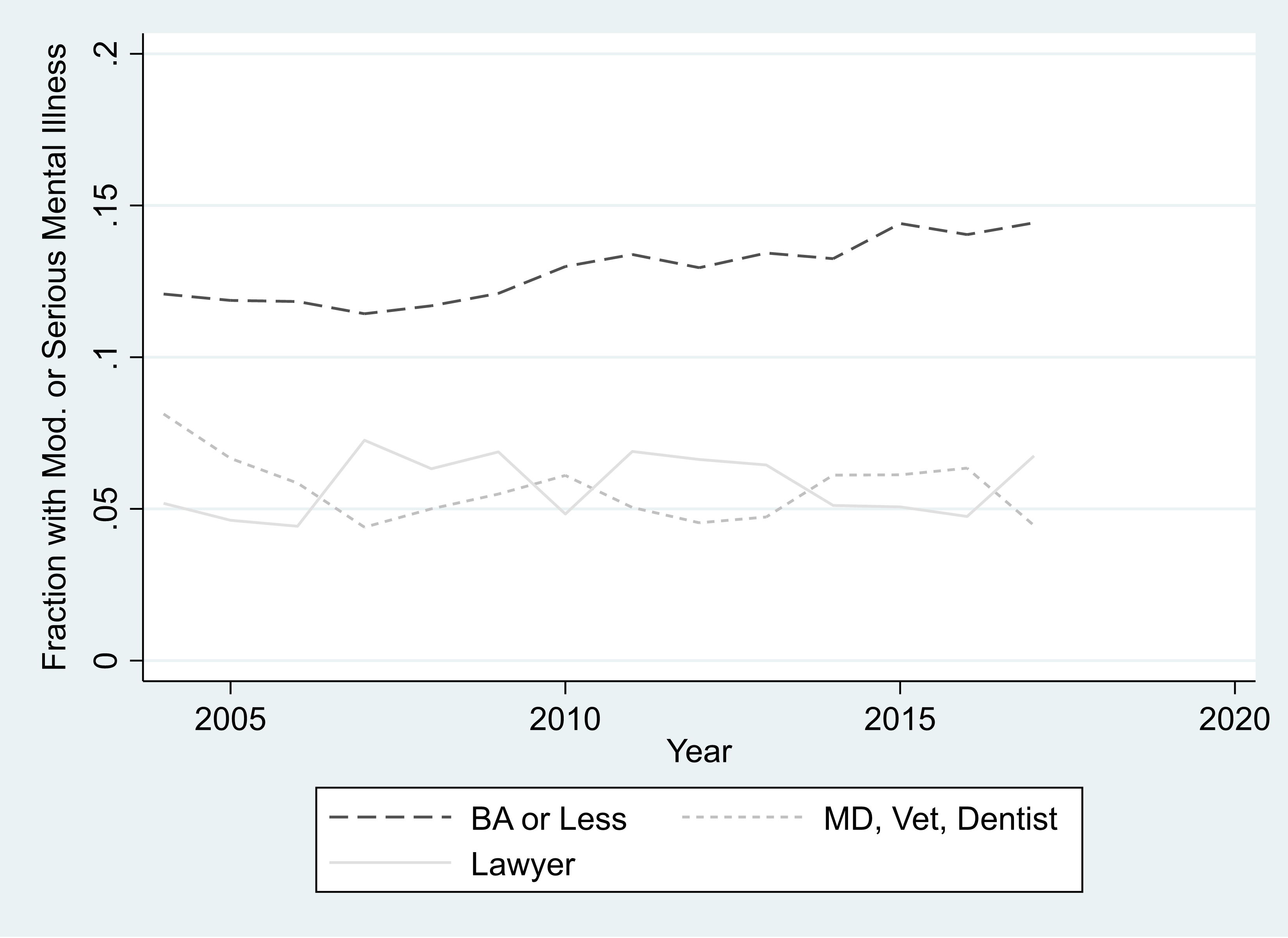

A cursory look at the NHIS sample shows that lawyers reported much lower incidences of mental illness, both moderate and serious, than the entire sample. Although 3.7 percent of the entire sample reported serious mental illness, only 0.7 percent of lawyers did so. Similarly, 12.8 percent of the entire sample reported moderate or serious mental illness, compared to 6.4 percent for lawyers. These differences are statistically significant. Further, reported mental illness among lawyers was no worse than that of medical professionals.

Figure 1. Serious mental illness among population with BA or less, medical professionals, and lawyers.

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Moderate or serious mental illness among population with BA or less, medical professionals, and lawyers.

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Other studies, including the one relied upon by the ABA National Task Force on Lawyer Well Being, "found that younger lawyers in the first ten years of practice and those working in private firms experience the highest rates of . . . depression." The NHIS data suggest otherwise: differences in mental illness between lawyers younger than 40 and their older peers were not significant, nor were differences between lawyers working in private firms and those working in-house or for the government.

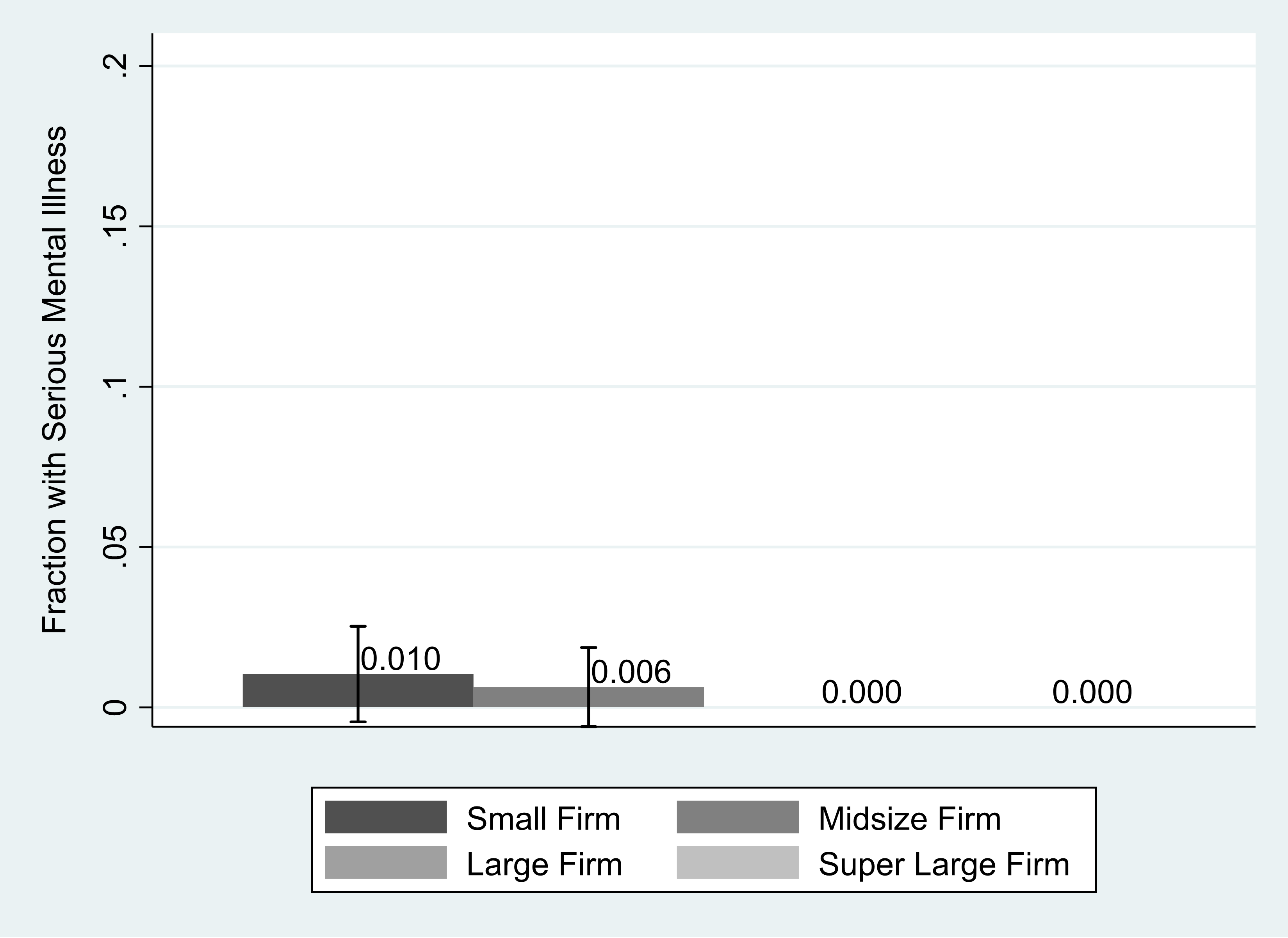

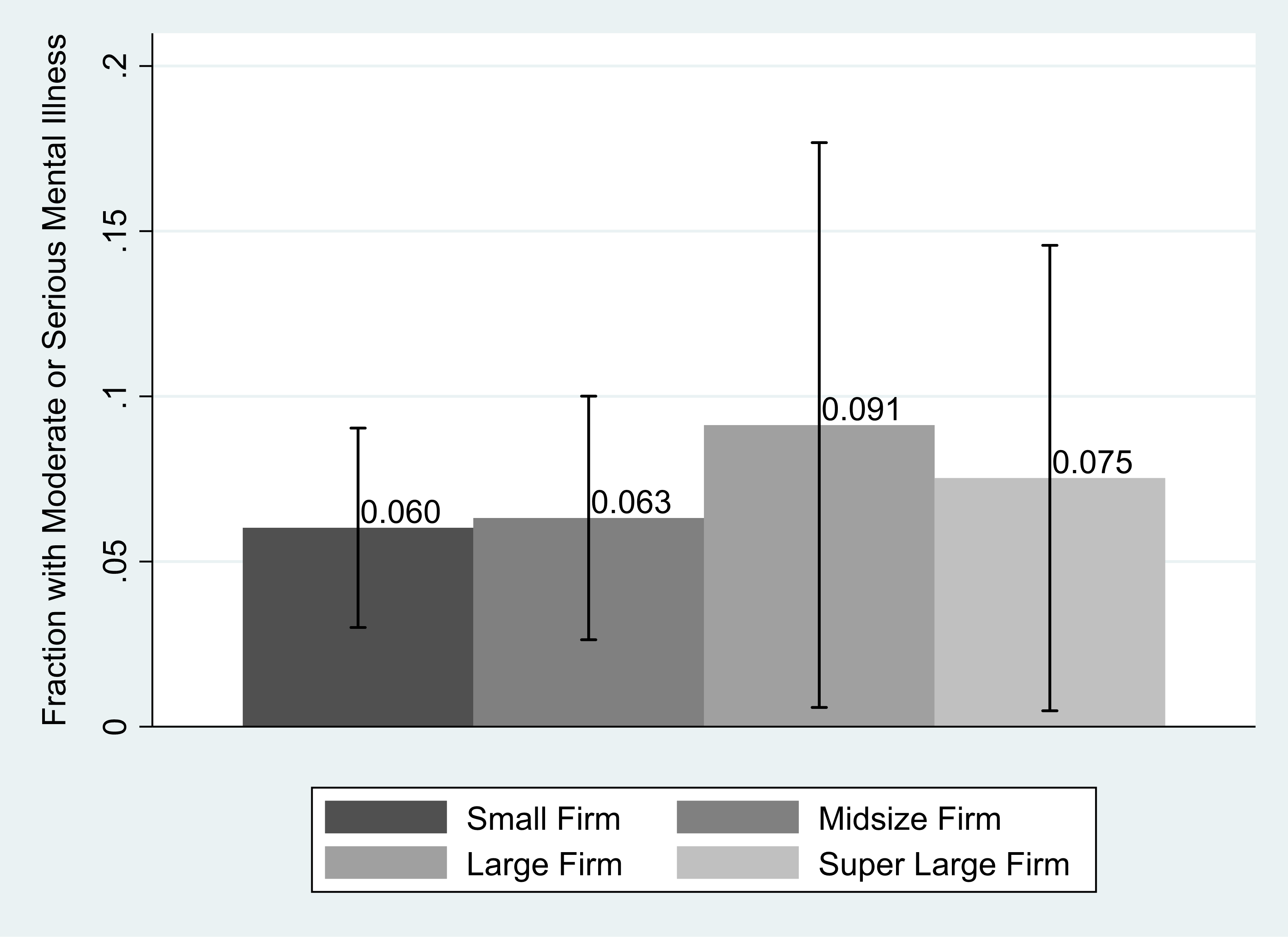

Many have argued that lawyers in large law firms are particularly prone to mental illness. To probe this hypothesis, we broke down incidences of mental illness among lawyers working at law firms of different sizes. We defined small firms as having fewer than 10 employees, mid-size firms as having between 10 and 99 employees, large firms having between 100 and 499 employees, and very-large firms having 500 or more employees. Lawyers at large or very-large firms reported a lower incidence of serious mental illness than their counterparts at smaller firms, significant at the 0.1 percent level. Differences in rates of moderate or serious illness were not significant. That said, at this level of granularity, sample sizes become so small that the results should be taken with a grain of salt. For example, no lawyers in the NHIS sample at large or very large firms reported K6 scores indicating serious mental illness.

Figure 3. Lawyers with serious mental illness by firm size

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Lawyers with moderate or serious mental illness by firm size

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Relying on surveys of volunteer respondents with low response rates renders any analysis of time-trends in lawyer well-being tenuous. If we compare very different surveys conducted in different years, then any observed trends may be attributed to genuine trends or to differences in survey methodology or response rates. It is therefore not surprising that longitudinal analysis of lawyer well-being is exceedingly rare. Relying on the NHIS data to study lawyer well-being, by contrast, allows us to study trends over time because the NHIS uses a common survey methodology over many years. Looking over time suggests that incidence of serious mental illness among lawyers declined slightly from 2004 to 2017, while the incidence of moderate or serious mental illness stayed relatively constant.

Figure 5. Fraction with serious mental illness over time

Notes: Three year moving averages, 2004-2017.

Figure 6. Fraction with moderate or serious mental illness over time

Notes: Three year moving averages, 2004-2017.

The NHIS data suggests that lawyers' mental health is actually better than the general population's, and no worse than that of medical professionals.

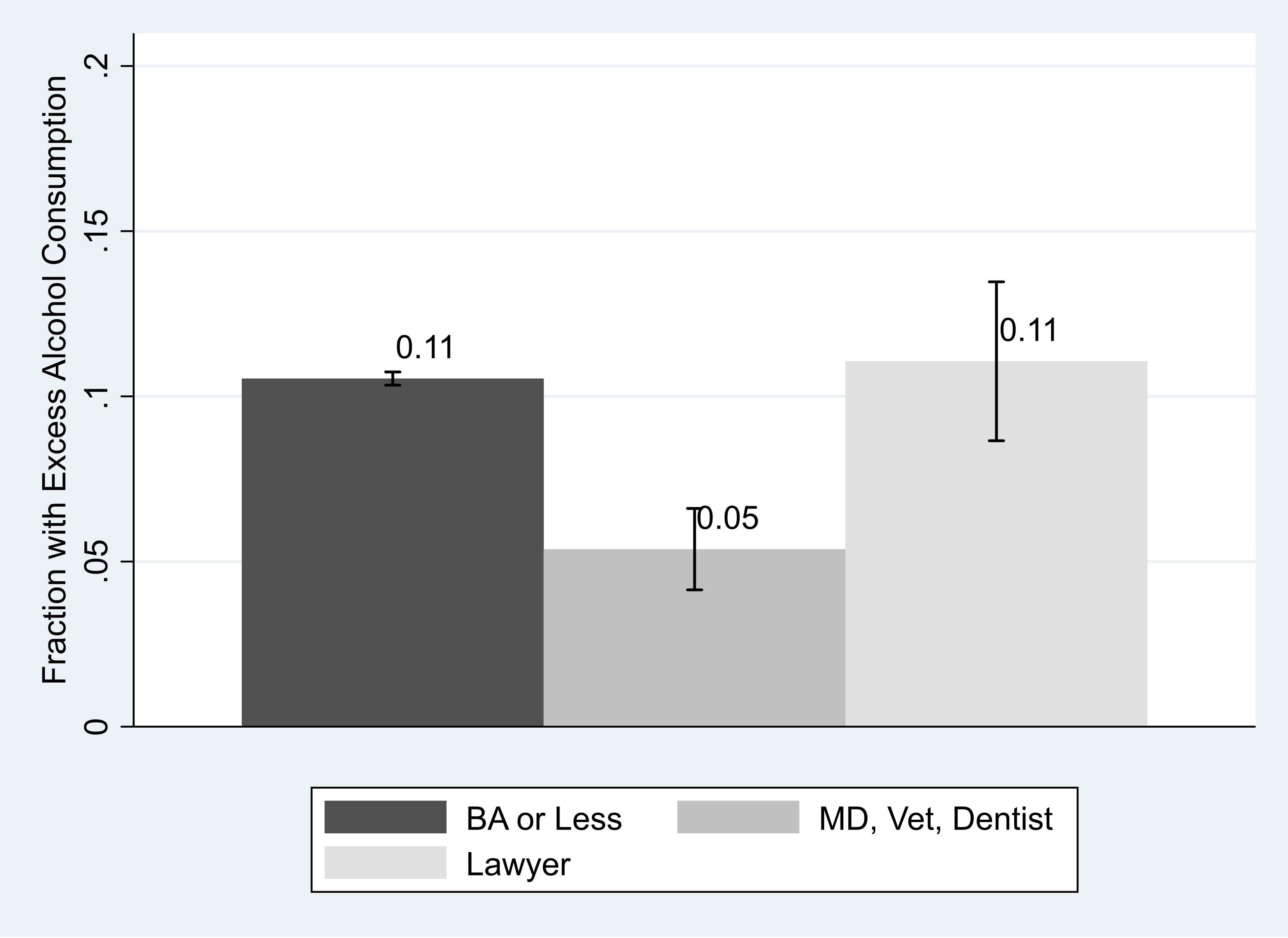

Alcohol Abuse

Problematic drinking data among lawyers presents a grimmer picture. Using a Center for Disease Control definition of excessive alcohol consumption—drinking five or more drinks on twelve or more days a year—reveals rampant alcohol abuse among lawyers in the NHIS sample compared to similarly educated professionals. Eleven percent of lawyers reported excessive alcohol consumption. Although only slightly higher than the overall NHIS population incidence, this figure is more than twice as much as the excess alcohol fraction reported by other similarly educated professionals such as doctors and dentists. This difference is significant at the 99% level.

Figure 7. Fraction Consuming Excess Alcohol

Notes: Three year moving averages, 2004-2017.

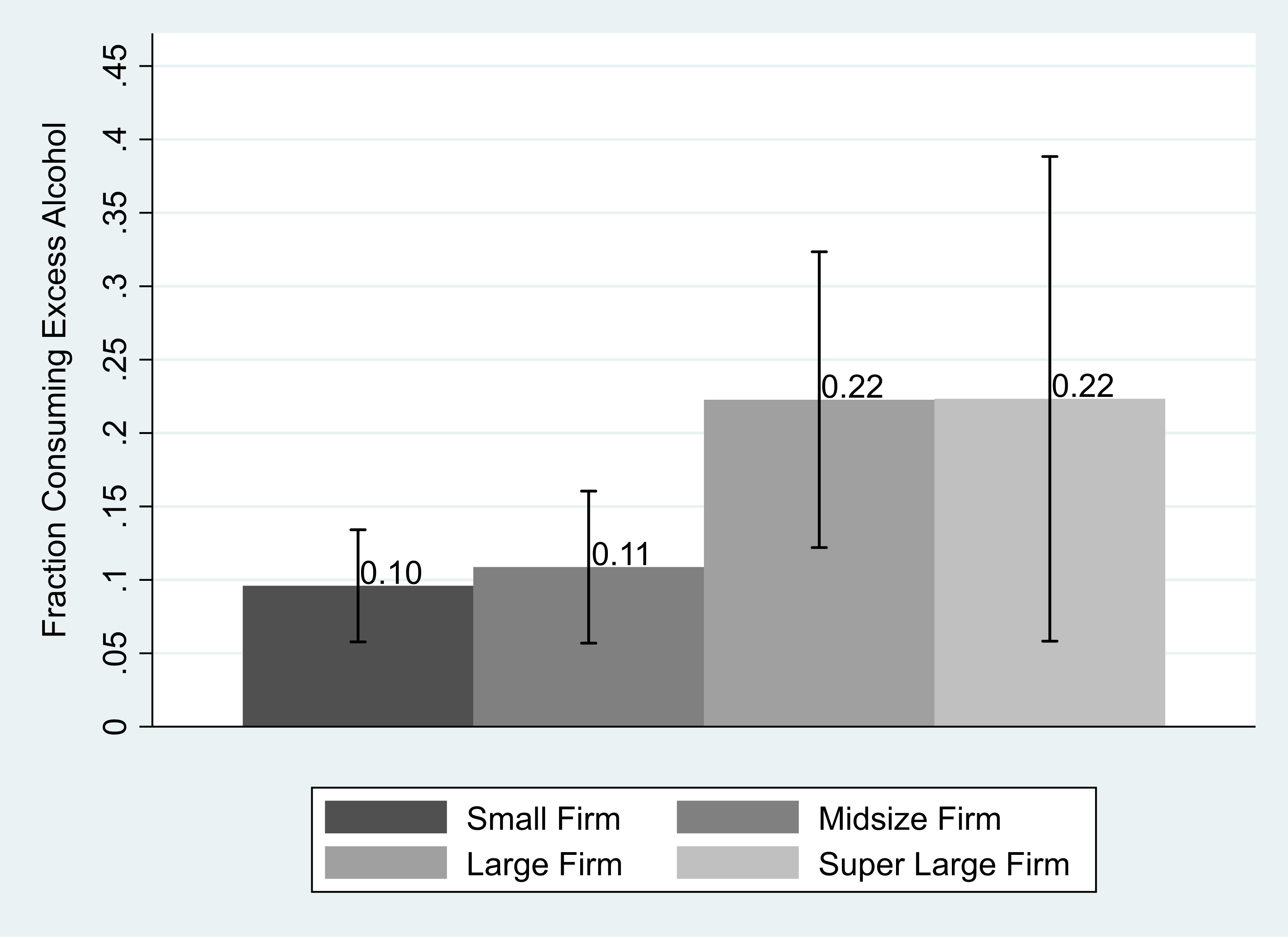

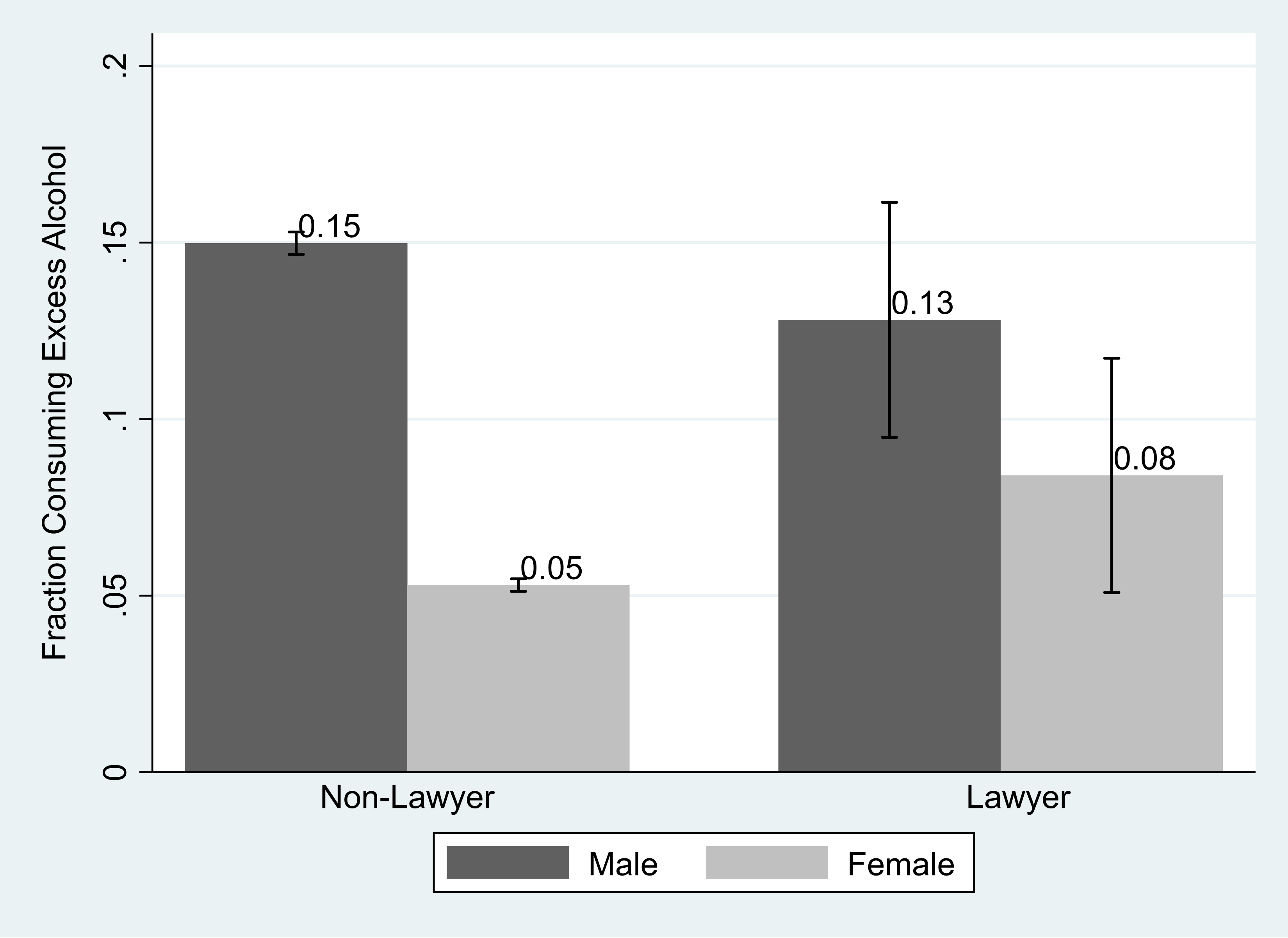

Demographic and firm data provide additional nuance. We found that lawyers at large (100-499 employee) and very large (500+ employee) firms reported much higher rates of problematic drinking than other lawyers, although the difference is not statistically significant at the 5% level due to small sample sizes. Further, male lawyers reported problematic drinking at 1.5 times the rate of their female counterparts, a difference significant at the 5 percent level.

Figure 8. Fraction of lawyers consuming excess alcohol by firm size

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 9. Population consuming excess alcohol by gender

Notes: With 95 percent confidence intervals.

Although lawyers consume excess amounts of alcohol at much greater rates than similarly educated non-lawyers, the rate reported in the NHIS (11%) falls far short of the rates derived from the ABA/Hazelden survey, which "found that between 21 and 36 percent [of lawyers] qualify as problem drinkers." That said, this may reflect the different instruments used to observe problematic drinking. The ABA/Hazelden survey used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, "a 10-item self-report instrument developed by the World Health Organization to screen for hazardous use, harmful use, and the potential for alcohol dependence."

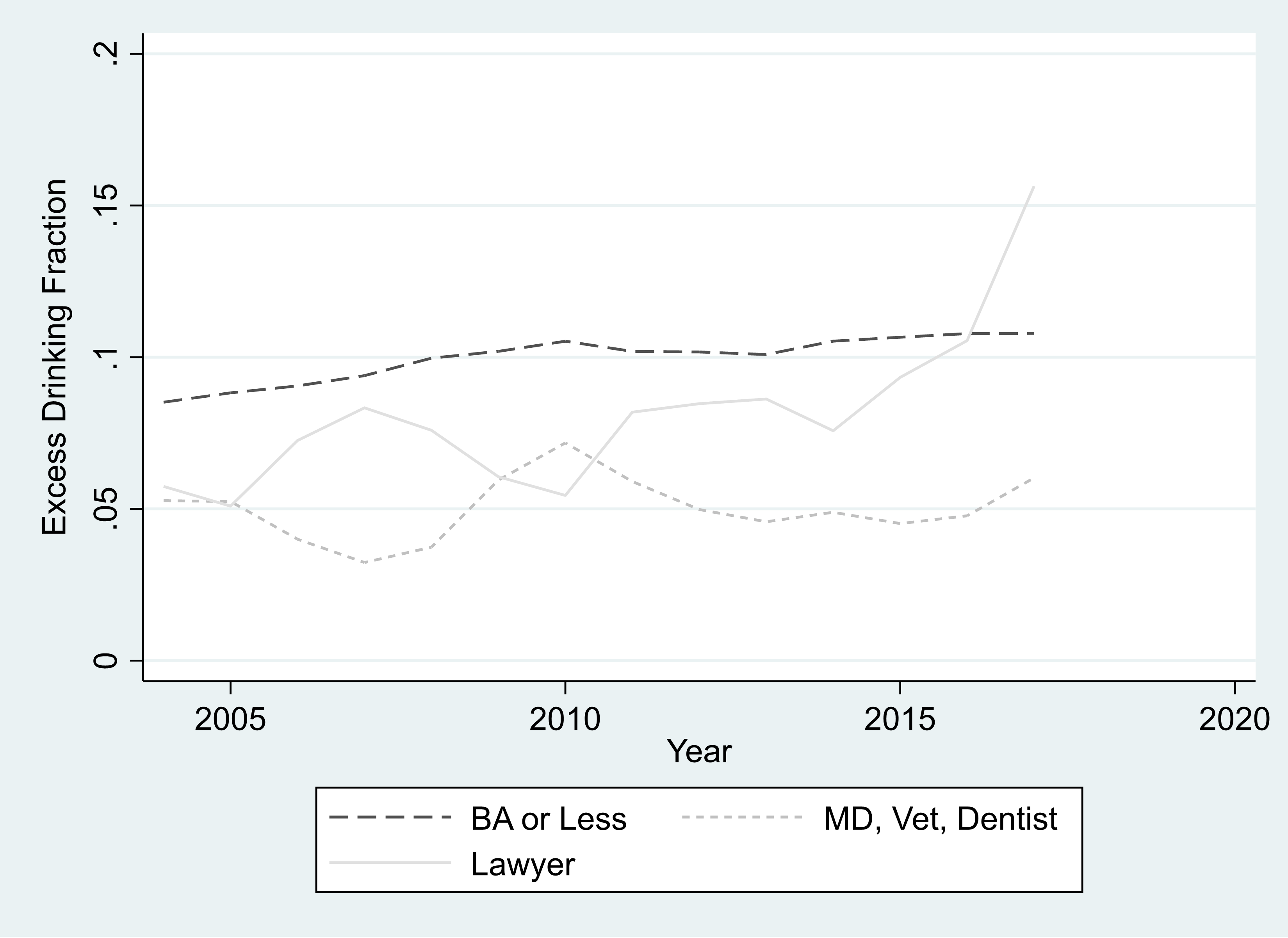

Time trends in lawyer alcohol abuse are similarly concerning. Problematic drinking rates among lawyers in the sample increased considerably from 2004 to 2017. By contrast, problematic drinking rates for other educational and professional categories show milder increases. Doctors, dentists, and veterinarians, for example, report a relatively steady problematic drinking rate throughout the period. The dramatic increase in problematic drinking rates for lawyers during this period thus represents a potentially troubling development that is particular to law, although standard errors remain high due to relatively small sample sizes. Identifying this previously unstudied trend is an excellent example of the possibilities unlocked by using annually repeated surveys such as the NHIS to study lawyer well-being in place of more ad hoc studies, even if those studies have larger sample sizes.

Figure 10. Fraction of population with excessive drinking over time

Notes: Three year moving averages, 2004-2017.

Overall, then, alcohol abuse appears to be a particular problem for lawyers, and one that has recently grown much worse. Reformers should evaluate the role of drinking within legal culture and consider ideas for reducing alcohol's role.

Even though lawyers do not report extraordinary levels of mental illness, mental health should remain a priority for the legal profession alongside limiting substance abuse. However methodologically sound and reliable, the NHIS offers a single source of data on lawyer mental illness with only nine hundred seventy-eight lawyer-observations. Moreover, the high rates of alcohol abuse reported by lawyers may indicate underlying mental health problems in the profession that are not well captured by K6 scores. To build more robust conclusions about mental health in the profession, we would ideally have more sources of data, including a large randomized survey of lawyers with high response rates. For the moment, however, the NHIS data suggests that the conventional wisdom of extraordinary rates of mental illness in the legal profession may be unwarranted.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I have at least 20 cases of beer — some mainstream, some craftier — in my garage and basement. Is that an alcohol problem?

Would it impair your judgment? Do you have any to impair?

So long as I am about to continue to prevail in the culture war against movement conservatives, I am content.

Retaining enough of my wits to continue to mock the vanquished clingers would be nice, too.

The Goths and Vandals were part of the wave of the future, too.

Prevail what?

Have you ever convinced anybody, of anything? But too be fair you’ve never even tried to make a substantive argument about anything.

He's prevailing vicariously. The actual prevailing is being done by people who'd likely shoot him in the back of the head and bury him in a mass grave if they genuinely prevailed, but he hasn't accepted that yet.

"Retaining enough of my wits...:

Half is better than none, right?

You bet it is. Unless you drink multiple bottle each day, some is bound to get skunked

I strive to put it to good use before freshness becomes a problem. Wasting beer is immoral.

1. Byline is wrong.

2. Figure 7 caption is copied from the timeline figures, not the bar charts.

perhaps the topic called for more of a "bar chart",,,

I guess I shot myself in the foot with that one!

I was already a fairly heavy drinker when I got to college, but my first year classmates and I took boozing to another level in law school.

I have a problem with the overly sophomoric nature of a psychological evaluation based on just six questions.

Hey, be grateful. That's five more than the "do you support Trump?" screening tool of late.

Drinking, at least in the private sector, was on its way out in the 2000's and by 2008 was a shadow of its former self. The comes in the recession which rolled back the last of discretional expense accounts. Add stagnant wages with increased work loads and "professional" drinking was done except for maybe higher end corporate dinners or travel.

Then comes "me too" and just more general CYA risk management at work and anyone who is mid-level or higher won't touch booze around co-workers. I'm sure that didn't sober up the workforce overnight and drove drinking to smaller, closer knit groups or just individuals doing so at home.

"Drinking, at least in the private sector, was on its way out in the 2000’s and by 2008 was a shadow of its former self."

Where in the fuck do y'all come from?

The law school dean was asked to fill out a form listing all faculty broken down by sex. He wrote "Zero, but six have been broken down by alcohol."

"drinking five or more drinks on twelve or more days a year"

Looks like I have to up my game. Can't fall behind my peers.

I get around that by drinking four bourbons before midnight and another four after.

So, the lawyers are drinking more, and less mental health problems.

Self-medicating effectively? Maybe just leave them be.

Alcohol, for all of its potential pitfalls, is a decent drug for anxiety and depression. You will never hear a mental health professional acknowledge that but as a drug it is 1) cheap, 2) works fast, 3) has minimal side effects when dosing is followed, 4) delivers desired relief for controllable and predictable periods of time, and 5) is available just about everywhere. Just like people use aspirin fine on a daily basis, many also use alcohol to "self medicate" successfully.

Of course, there are many negatives to alcohol including addiction, over consumption, etc. But as a drug, if it were not alcohol and just anything else, we would declare it to be the public health achievement of the century.

This is dead wrong. If you want to make this argument about marijuana, that would be one thing.

But alcohol is among the most dangerous drugs ever invented. It is highly addictive, leads people to be more conflict-prone and violent, impairs judgment and memory, induces over-confidence, and makes numerous ordinary human activities profoundly dangerous.

And the reality is a lot of the people who think they are using alcohol to "self medicate" successfully are actually under dangerous delusions. You see, one of those things I mentioned is "impaired judgment" and another was "induce overconfidence", and one of the ways this manifests is that people who use alcohol are often highly deluded or in denial about all the harm they are causing and all the negative effects it is having.

This is not accurate in the least. Every substance can be abused. Everything is life has its pluses and minuses. Declaring all the banes of alcohol like they apply to the hundreds of millions of people that consume alcohol without experiencing any of the pitfalls and then pronouncing it as the ultimate evil is not even remotely accurate.

And when you balance the negative pitfalls of alcohol with other "medicines" available they are not nearly as bad by far.

The fact that they don't "experience" all the harm is a lot different from saying no harm is done. The fact that alcohol makes its users believe it is not causing harm or impairing them when it is, is one of the most dangerous aspects of this drug.

Alcohol equaling "the devil's juice" is an old and tired trope which is not the least bit accurate and treating it as such has had detrimental effects to society.

Whereas the potheads get all that, but just don't give a shit.

Sheesh. Alcohol is highly addictive for a fairly small minority of people outside certain racial groups. For most people it isn't addictive at all.

Some people it makes more conflict prone and violent, other people the opposite. As they say, in vino veritas, and it brings out different truths in different people.

It certainly impairs judgment and memory, while you're under its influence. I would not recommend drinking while operating power machinery. Would you recommend drinking under the influence of any psychoactive compound besides maybe some weak stimulants?

I think people treat equivalent drugs differently because they are dispensed by a doctor. Benzos are exceptionally dangerous drugs, addictive, and mimic the effects of alcohol, but I have known people who pop those things like candy because their false perception is that their doctor would not prescribe them if they were not fine.

The chief advantage of alcohol from an addiction standpoint is the hangovers if you drink too much. I understand that the people who don't get hangovers are the ones at real risk of addiction, because it seems all positive and no negative until the liver damage sets in.

Paradoxical that being toxic like that actually makes alcohol less dangerous, isn't it?

Now you've taken up with hangovers?! I hate you so much.

Alcohol is highly addictive for a fairly small minority of people outside certain racial groups. For most people it isn’t addictive at all.

This is true of many "addictive" drugs. The thing is, even people who aren't alcohol "addicts" also do a bunch of destructive stuff while under its influence.

If we're trying to evaluate the net harm from alcohol, how do you propose we isolate the benefits of alcohol for people who self medicate? That is, how do you know you're considering all the harm mitigation by alcoholics who, if they didn't consume in excess, would engage in other destructive behavior?

"But alcohol is among the most dangerous drugs ever invented."

Especially if you're a bad time!

"....is that people who use alcohol are often highly deluded or in denial about all the harm they are causing and all the negative effects it is having."

Have you considered that people who do not use as much alcohol as me are highly deluded or in denial about the harm, instead?

We have extensive statistics on the harm of alcohol. This isn't some unstudied area.

I AGREE.

The California Bar (I mean the one that regulates lawyers) has been aware of this for years. Every 3 years during my over two decades of practice, I have had to take a CLE class on alcoholism in the legal profession.

This is certainly the result of the California Bar's sober, careful review of the literature, and definitely not the idiosyncratic result of an arbitrary regulation imposed due to one or two high profile lawyers suffering from serious alcohol-related harms. We all know that groups of lawyers are incredible legislators and regulators, and when they act, it is because of the facts, and not just a bunch of bar flies self-promoting and padding their resumes.

NToJ:

People's lives are ruined by alcohol. Including lawyers and their clients and family members. I think the people who run the California bar understand this, and I'm glad they are in charge of that issue and not the Drinking Caucus in this comments thread.

The California bar is not "in charge" of the issue of alcohol. They're in charge of CLE requirements for California lawyers. Is there "extensive statistics" on the effects of California's CLE requirements on alcohol use by lawyers? Even assuming I agreed with you on the scope of the problem--which I don't--you'd still have to persuade me that having you take a CLE every three years on alcoholism has any meaningful effect whatsoever on the harm. But even if you could prove a harm reduction result from the CLE (which I doubt), you'd still have to weigh that against the cost of the program on whomever pays for it. My guess is it is on Californian consumers of legal services or, just as likely, California consumers who would like to purchase legal services, but can't afford to do so because of things like mandatory CLEs for alcohol awareness.

Are you certain that the people enriched by the program aren't part of the Temperance Industrial Complex?

I took such a CLE course this year also It was quite reasonable

The graphs seem to tell the story fairly clearly that mental illness is inversely correlated to educational level. That hardly seems shocking, and is reinforced by the nearly equal degree of mental illness in two disciplines that are vastly different, but in both of which you generally have to be able to hold it together to graduate and practice in the first place.

So the point of throwing "but... lower mental illness then genpop!" in the mix isn't immediately clear to me. A skewed sample measures differently than the population as a whole. So what?

Question. How is "lawyer" defined relative to "BA or less" and "medical professionals"? If lawyer and medical professionals are defined by licensing regimes, it may be undercounting serious mental health issues with former lawyers and medical professionals. Since those licensing regimes could have the effect of weeding out (by disbarment) lawyers who succumb to serious medical health issues, the data will have a serious survivorship bias. And this will run only in one direction, since a person with "BA or less" who succumbs to serious mental illness, will not have their "BA or less" qualification taken from them by any licensing regime.

There's more than survivorship bias - it's a bar of entry into the category in the first place!

How many people with serious mental illness are capable of becoming lawyers or doctors in the first place? It seems unlikely that many alcoholics can focus enough to get the degrees to even potentially enter those categories, which makes it very easy to keep the numbers of patients down.

I agree with you re: mental health. But what the data suggests is that alcohol is not an impediment to becoming (and remaining) a lawyer, since the data shows lawyers are equal to or more likely to consume excess alcohol than BA or less category. If we assume for the sake of argument that excess consumption of alcohol does interfere with becoming or remaining a lawyer, that would imply a greater correlation between excess consumption of alcohol and becoming or remaining a lawyer.

Part of the problem is that the chart doesn't actually measure alcoholism, it measures "excessive consumption of alcohol" which is a significantly different thing - and not a mental illness, whereas alcoholism is.

So even though a common definition and measure is available, these two have instead chosen to use a different one for alcohol use (also different from the on the ABA uses).

I'd be much more interested in a chart measuring alcoholism, rather than the vague and potentially harmless "excessive use of alcohol".

Your graphs could make everyone look a lot better if you included PhD’s in at least the mental illness graph. But just limiting the cohorts to BA or less, MDs and lawyers can probably be justified because you don’t have to rescale the graphs or make the scale logarithmic to show the PhD’s.

So let me get this straight… Someone who has five glasses of wine one night every month, but abstains from alcohol every other day of the year, is a “problem drinker”? What about someone who has four drinks on 20 occasions every year? That person is OK by comparison?

Shouldn’t the definition of “problem drinker“ be tied to whether drinking adversely affects one’s‘s health, employment, family life, or other critical life functions in a significant way? Rather than some arbitrary number that appears to have been pulled out of a hat?

And about the rate of “problem drinking” at large firms: They tend to hire large number of attorneys in their 20s and early 30s, who tend to be single, childless, and persons who live in cities with restaurants, bars and clubs readily accessible. People that age can hit the “five drinks in 12 days“ standard in a single summer.