The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How Bills of Exchange Went from a Way to Bring Textile Proceeds Home to the "Foundation of Modern Commercial Banking"

Many textile merchants wound up as bankers. These useful IOUs were a major reason why.

This is my last guest post of the week, and I'd again like to thank Eugene Volokh for inviting me to share some selections from The Fabric of Civilization. These posts on "social technologies" are all taken from chapter five, "Traders."

Thomas Salmon had a problem. As a tax collector in Somerset, Salmon had amassed thousands of pounds of gold and silver that needed to get to London. But the England of 1657 had no checking accounts, wire transfers, or armored cars. Physically traveling with that much specie was difficult and dangerous. What was Salmon to do?

He took the coins to local cloth makers, known as clothiers. In return, they gave him slips of paper called bills of exchange. These bills worked like checks, but instead of drawing on a bank they told a London businessman named Richard Burt to give Salmon cash. Burt bought woolen cloth from scattered producers and sold it to London merchants, taking a commission from the sale.

When he sold their goods, Burt kept the clothiers' credits on his books, and they drew down their accounts with bills of exchange. A Somerset clothier could buy household provisions from a local merchant and pay with a bill of exchange. The merchant would cash the bill on a trip to London or, more likely, use it to pay his own suppliers who had dealings there. Accepting coins from the tax man was yet another way for clothiers to cash in their credits. Salmon would carry the bills of exchange to London, swap them for specie at Burt's, and deposit the money at the treasury. An institution created to serve the textile industry had become crucial to the finances of the British Crown.

Originating with Italian textile merchants in the 13th century, bills of exchange have been called "the most important financial innovation of the High Middle Ages." They started as a way for merchants to transfer proceeds from the fairs at Champagne back to the home office. Written in a kind of shorthand, these slips of paper were essentially form letters telling an agent, usually a bank, in another city to pay someone a certain amount; when a merchant issued a bill of exchange, his local bank sent a notice to its foreign branch, telling it to honor the bill when presented. Bills of exchange were not official, state-sanctioned documents, designed in advance but, rather, social technologies that evolved through trial and error. Their usefulness depended on connections and trust.

As merchants built up networks of offices in multiple places, bills of exchange became increasingly flexible. By the early 14th century, you could cash one in most major cities in western Europe. Whether to buy wool or pay armies, coins no longer needed to be hauled over land and sea. "Bills of exchange," historian Francesca Trivellato writes, "were the invisible currency of early modern Europe's 'international republic of money.'"

Although bills began as a way to easily transport funds and convert foreign money, they quickly evolved other uses. For starters, they addressed the shortage of currency by enabling many more transactions with the same amount of specie.

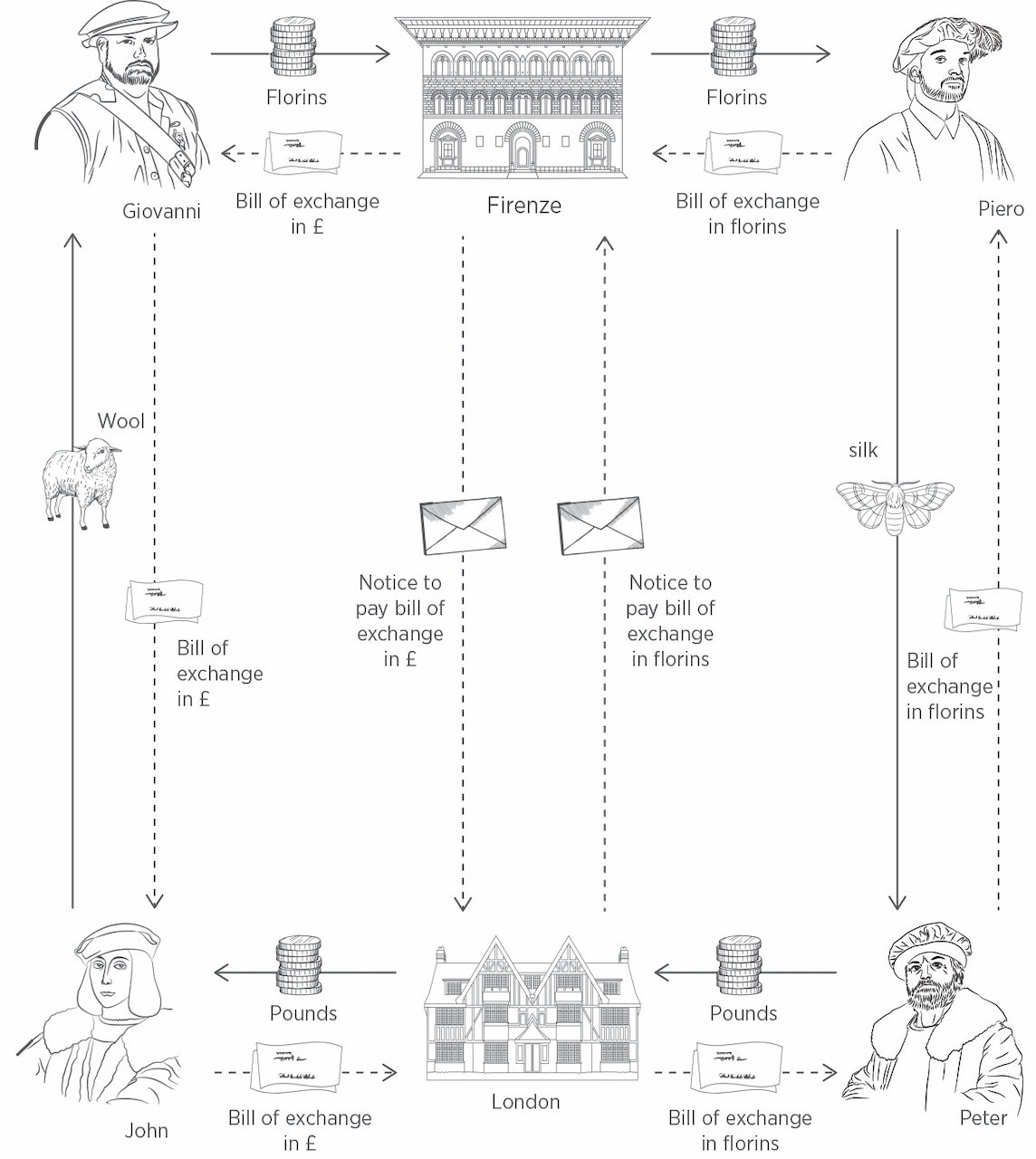

To see why, consider two hypothetical English businessmen. The first ("John") exports raw wool, selling it to a Florentine merchant ("Giovanni") for a bill of exchange payable in London. The second ("Peter") imports silk fabric, buying it (from "Piero") with a bill of exchange payable in Florence. On the banks' books, the two bills can be offset against one another, with only the difference actually changing hands as currency. A small supply of coins can enable many more exchanges. "Such a system could be incredibly efficient," writes economist Meir Kohn. "For example, between 1456 and 1459, one bank in Genoa received 160,000 lire in payments from abroad in bills of exchange, and only 7.5% of this amount was settled in cash: the remaining 92.5% was settled in bank."

Bills of exchange also provided credit. In its simplest form, they gave users a float. A bill was made payable not immediately but after a certain period, or usance, from its date of issue. The usance was somewhat longer than the usual travel time between the two cities, ensuring that notice to honor the bill could reach the payer. The cushion added an extra grace period to the short-term loan.

Over time, merchants figured out ways to turn bills of exchange into overt loans. In a common but oft-condemned practice known as dry exchange, the first bill of exchange was paid not in cash (or an account offset) but with a new bill of exchange that simply reversed the original one. This paper swap created an interest-free loan twice as long as the usance. Lenders could extend the terms by adding multiple round-trip exchanges.

With a slight variation, dry exchange could dodge bans on charging interest. The trick was to alter the exchange rate on the return bill. If, for instance, a merchant in Bordeaux exchanged 100 livres for an original bill payable for 140 guilders in Amsterdam, the return bill might repay the 140 guilders with 105 livres in Bordeaux.

Over time, bills of exchange became negotiable. You could transfer a bill originally made out to you simply by signing the back. The signature conveyed the legal obligation for you to make good on the underlying debt if the bill couldn't be cashed. Once bills of exchange were negotiable, they became more liquid. If you needed cash, you could sell your bills at a discount off their face value, just as bonds change hands today. Or you could issue a new bill of exchange and sell it at a discount to a money broker to redeem later. At least in theory, there was no limit to the number of times a bill could be endorsed, passing from one owner to the next.

"The product of this evolutionary process—the discounting of negotiable bills of exchange—was a financial invention of enormous economic importance," writes Kohn. "Indeed, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was to become the foundation of modern commercial banking."

Negotiability made bills increasingly useful in everyday commerce, outside of specialized money markets. Although no one had to accept them as payment—bills of exchange were not legal tender—if people trusted the signatories, they were nearly as good as cash.

Despite risks of default, bills of exchange endured, fading from everyday commerce only when superseded by currencies from central banks. As late as 1826, a Manchester banker testified to their continuing popularity, telling a parliamentary inquiry that he'd seen £10 bills of exchange circulating with a hundred or more signatures. "I have seen slips of paper attached to a bill as long as a sheet of paper could go," he said, "and when that was filled another attached to that."

Show Comments (21)