The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Justice Fields's Docket Book (October Term 1885)

Yick Wo v. Hopkins and Presser v. Illinois were decided that term.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, Supreme Court justices used so-called "docket books" to keep tracks of the votes cast at conference. These leather-bound volumes were printed with the names of hold-over cases. As new cases were added, the clerk would write in the new information on blank pages. The docket books were eventually phased out after the October Term 1945, and replaced with three-ring binders.

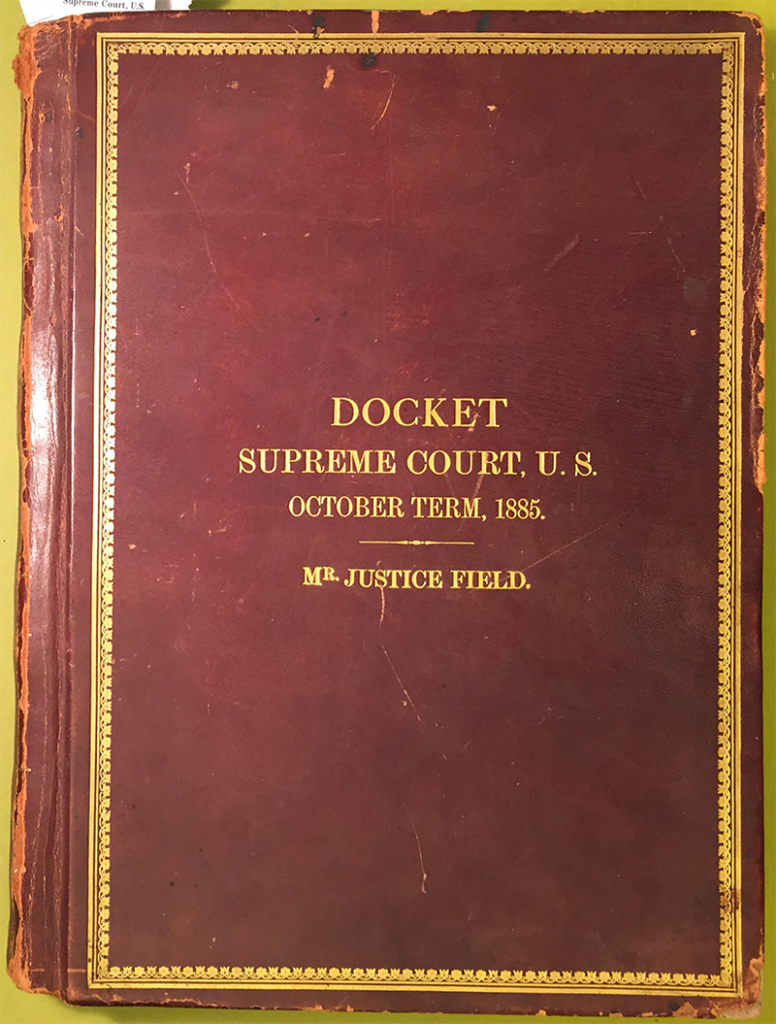

Recently, the Supreme Court acquired Justice Stephen Field's long-lost docket book from October Term 1885. Alas, the book does not contain any marks in Justice Field's handwriting. The Supreme Court Historical Society described the discovery:

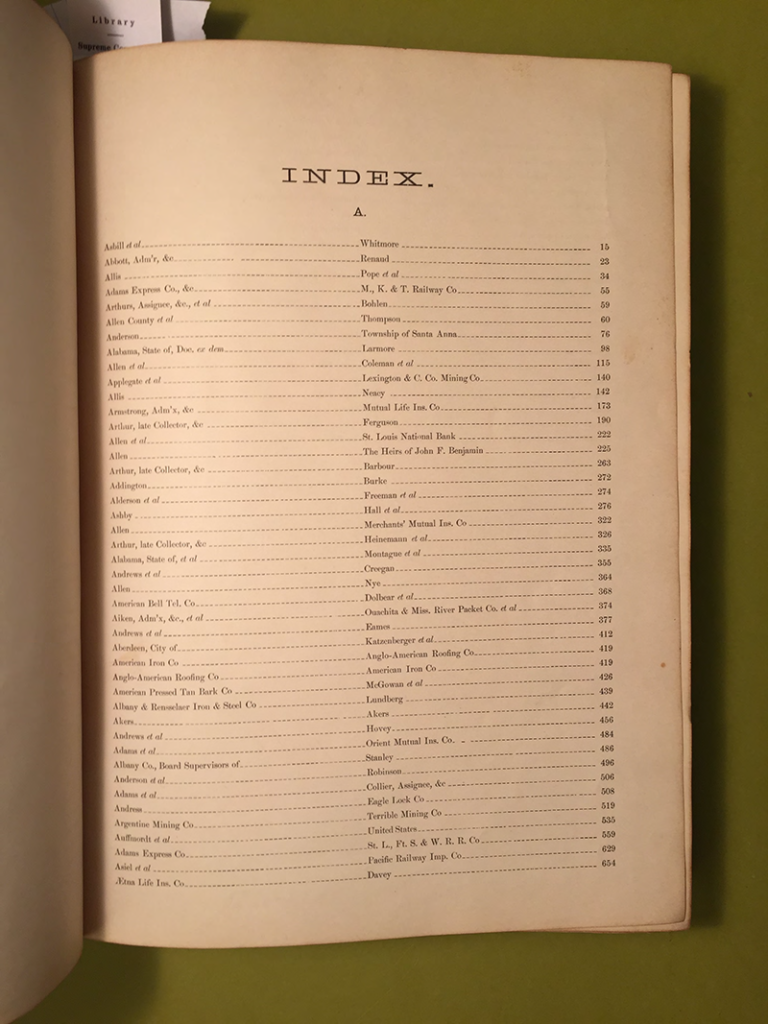

The book lists cases on the docket but also the attorneys who argued them, including Belva Lockwood who became the first woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court in 1880. Future Justices Melville W. Fuller and George Shiras, Jr. are also listed as advocates. During the 1885 Term the Court docketed 1,348 cases and disposed of 444. Field's biographer, Paul Kens, author of Justice Stephen Field: Shaping Liberty from the Gold Rush to the Gilded Age (1997), says Field wrote many opinions that Term and that the book's discovery is "really exciting."

How the book survived is still a bit of mystery, including how it ended up near Richmond. It is presumed that Field or his staff destroyed his Supreme Court papers and docket books after his retirement in 1897, because no significant collection of his papers exists today. The 1885 Docket Book must therefore have left his possession earlier. The rest of Field's personal law library was donated by his widow, Sue Field, to the Stanford University Law Library around 1900, but none of his other docket books are located there today.

Here is the cover of the volume:

Here is the index. All of the hold-over cases were printed in the volume.

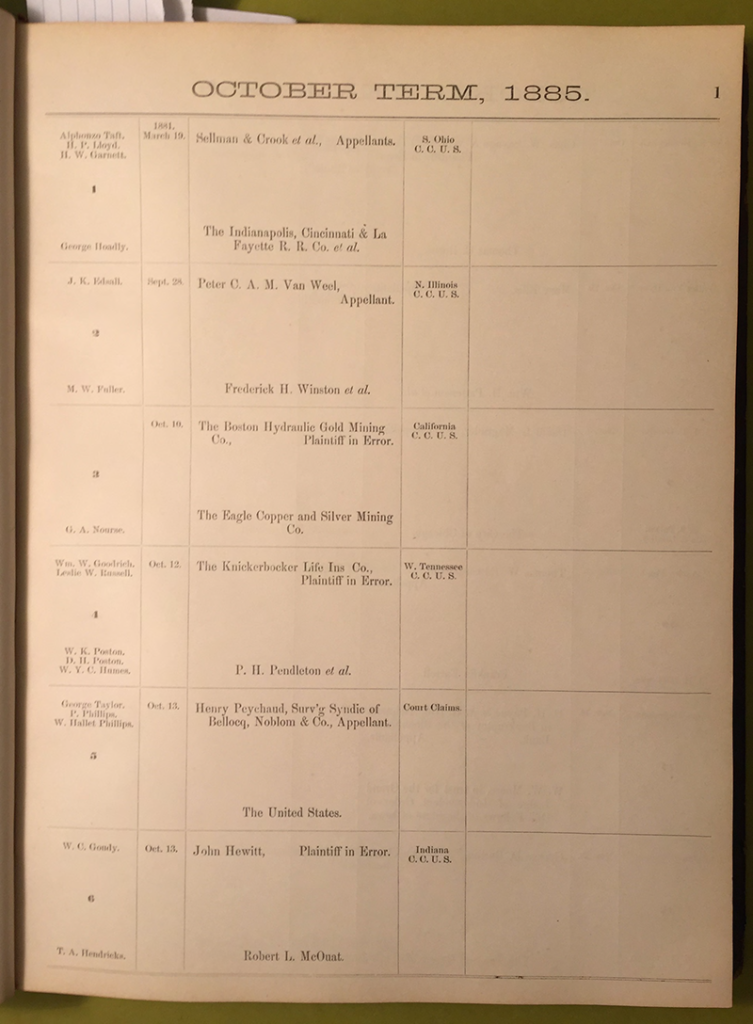

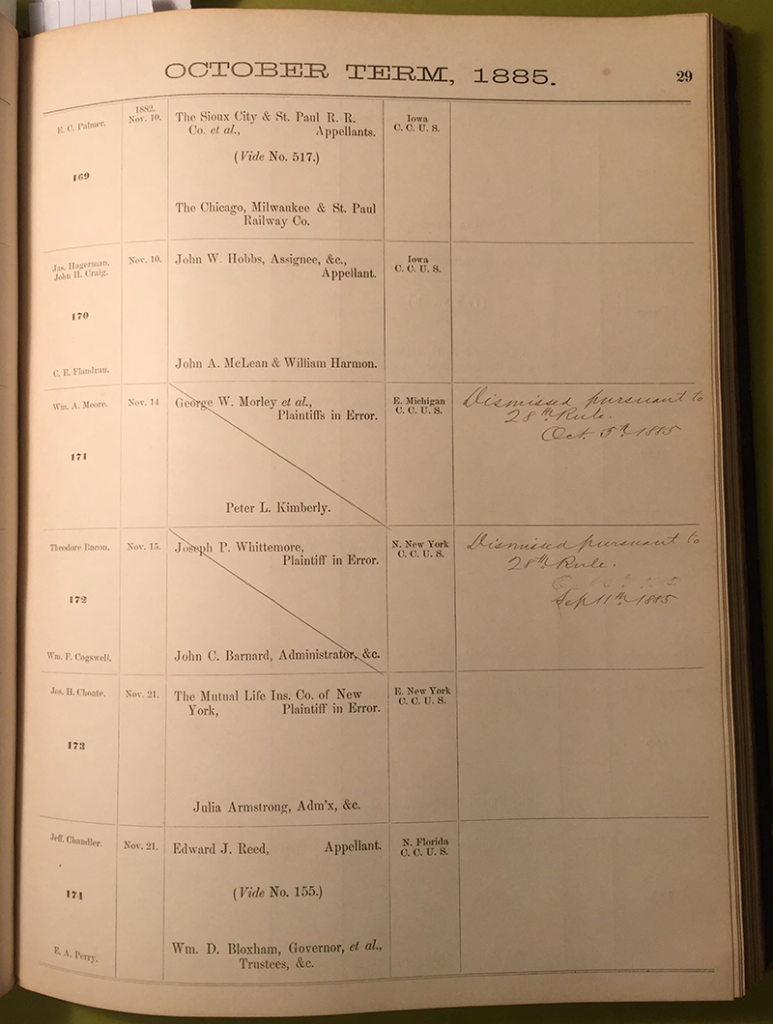

For each case, the docket book listed the arguing attorneys, the case name, as well as the lower-court.

And when a case fell of the docket, it was literally crossed out of the docket book.

And when a case fell of the docket, it was literally crossed out of the docket book.

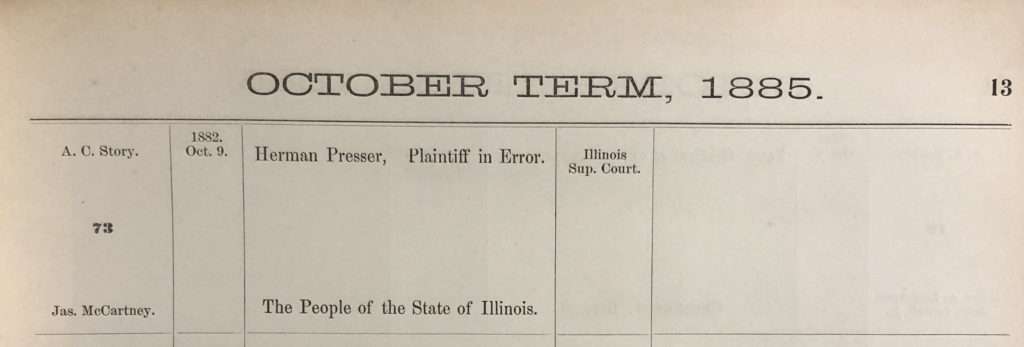

There were two prominent cases decided during OT 1885, First, Yick Wo v. Hopkins (118 U.S. 356) was argued on April 14, 1886, and May 10, 1886. Second, Presser v. Illinois (116 U.S. 252) was decided on January 4, 1886. The latter is an important Second Amendment case.

I asked Matthew Hofstedt, Associate Curator of the Supreme Court, if he would be willing to share the entries for these cases. He kindly sent the below graphics.

Presser, which had been scheduled the prior year, was printed on page 13:

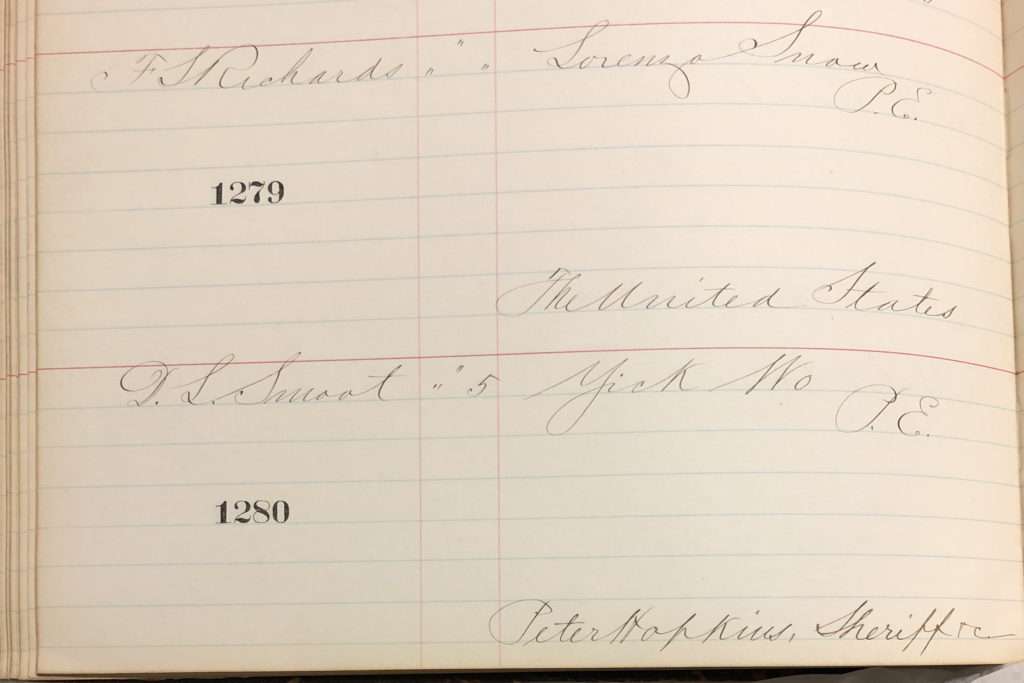

The entry for Yick Wo was hand-written because it was a new case. This section stretched across two pages.

Here is the left side of the page. The entry lists the petitioner as "Yick Wo," with the notation "P.E." (Plaintiff in Error). His attorney is D.L. Smoot. The respondent is "Peter Hopkins, Sheriff."

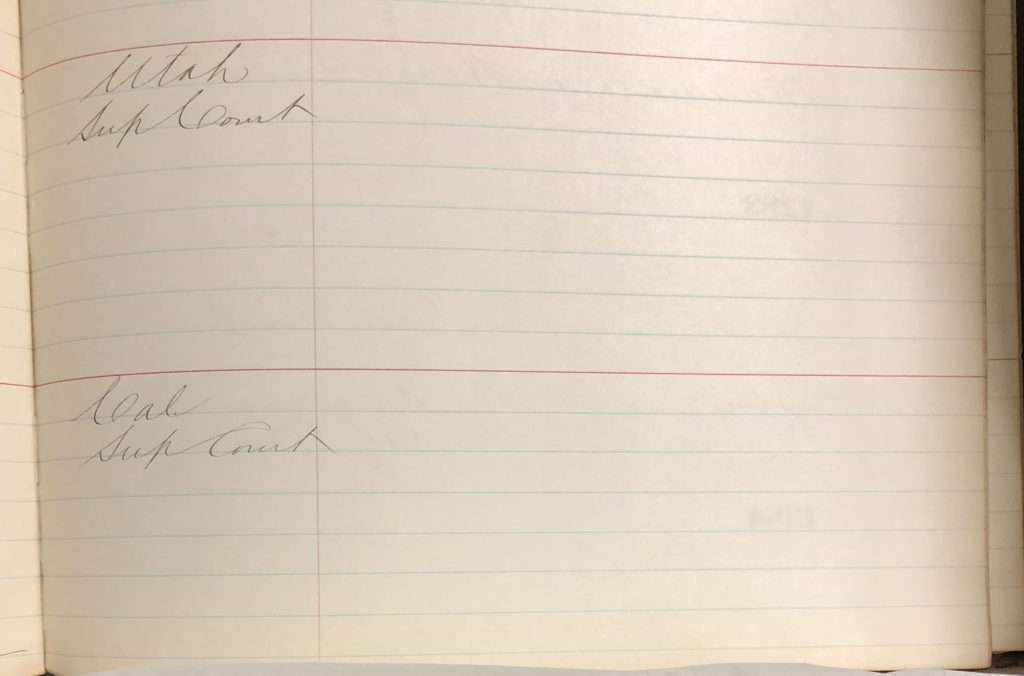

And here is the right side of the page. You can see the reference to "Cal Sup. Court."

Thanks again to Matthew for sharing these important files.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

IANAL. What is the difference between a Plaintiff in Error and an Appellant? I haven't seen the former term before.

I don't think there is one.

The docket book has some of the petitioners listed as Plaintiffs in Error and others listed as Appellants, so certainly there was a distinction at the time?

The differences arises from the way in which the case was brought to the Supreme Court from the lower court, a distinction that no longer exists. Cases at law were brought to the court by writ of error, and the parties in such a case would be the Plaintiff in error (the party that lost below and sued out the writ) and the Defendant in error (the winning party below). A writ of error was a review of the law in the case and the legal conclusions drawn by the lower court (where a jury had typically determined the facts).

For cases in equity and admiralty, which traced their roots to the civil law, a case was reviewed by the Court under an Appeal (where the term has a narrow meaning rather than the broad meaning it has today). An appeal was a review of the law and facts of the case (where the trial judge typically determined the facts in these two types of cases), as opposed to a writ of error. In a case heard on appeal the moving party (who lost below) was the Appellant and the party who prevailed below was the Appellee. As a quick shortcut then, you can generally tell whether a Supreme Court cases during this period was one at law or in equity or admiralty (although the latter introduced other labels, such as claimant and libellant) depending on the labels following the parties.

The writ of error was at some point eliminated by statute (I think either the late 19th century or the Judges Bill of 1925) and certiorari was added as a discretionary mode of review (a writ of error was a writ of right, whereas certiorari is at the discretion of the higher court). Certiorari and Appeal were then the methods of having a case heard at the Court, with the latter still applicable in equity and admiralty cases. And, Petitioner came to be used to designate the party that was petitioning the Court for to grant the writ of certiorari and hear the case (but not to be confused with the older extraordinary writ of certiorari that the Court granted in early 19th century cases).

Thank you for the comprehensive explanation!

One might even say this discovery is "interesting."

Starting in about 1892 Field's docket books had drool all over them. Or worse.

It's very interesting how little things have changed. Compare this booklet to the modern docket sheets like the one the Court released yesterday with October term 2020 arguments. The format, the contents, everything is exactly the same.