The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

How to Attend Oral Arguments at the Supreme Court

An in-depth look at the written and unwritten rules to attend oral argument at the Supreme Court

Last week, I attended oral argument at the Supreme Court in DHS v. Regents of the University of California (the DACA case). The experience was extremely problematic for reasons I will explain in a subsequent post. (I offered a preview on my Twitter feed.) This post will explain how to attend oral arguments the Supreme Court. The process is complicated for those not familiar with the written and unwritten rules.

Argument Days on the Court's Calendar

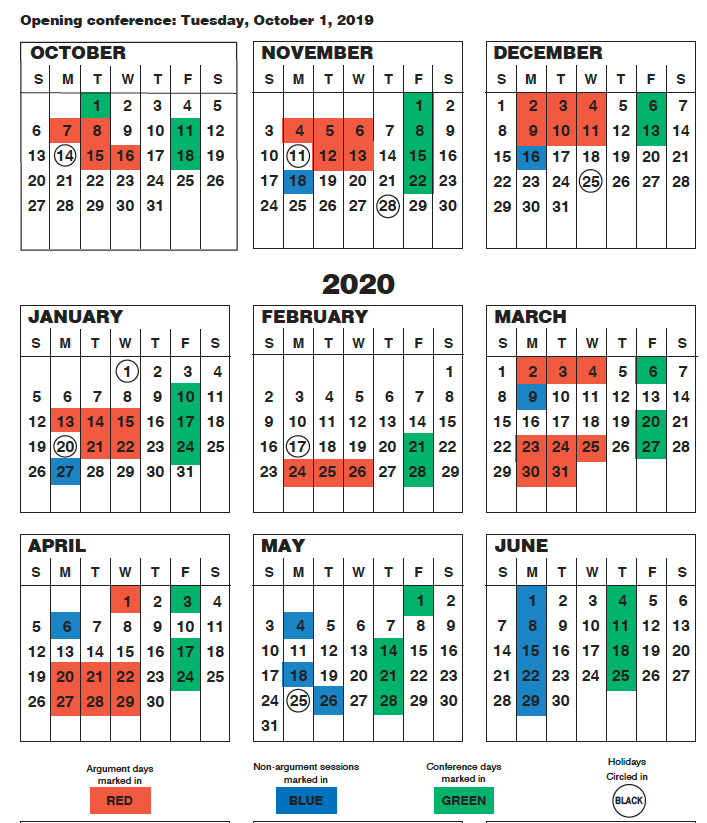

The Supreme Court's term begins on the first Monday in October. Every year, the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in approximately 80 cases. During the October 2019 term, for example, the Court scheduled 38 argument days between October and April. On most argument days, the Court hears two, one-hour argument sessions, starting at 10:00 a.m. Occasionally, the Court will hear a third case in the afternoon. The argument days are shaded in red on the Court's calendar. Non-argument days, in which the Court issues orders, hands-downs opinions, and admits people to the bar, are shaded in blue. And conference days, when the Justices privately meet, are shaded in green. Generally, the Court does not hear oral argument in May and June.

The Supreme Court's term begins on the first Monday in October. Every year, the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in approximately 80 cases. During the October 2019 term, for example, the Court scheduled 38 argument days between October and April. On most argument days, the Court hears two, one-hour argument sessions, starting at 10:00 a.m. Occasionally, the Court will hear a third case in the afternoon. The argument days are shaded in red on the Court's calendar. Non-argument days, in which the Court issues orders, hands-downs opinions, and admits people to the bar, are shaded in blue. And conference days, when the Justices privately meet, are shaded in green. Generally, the Court does not hear oral argument in May and June.

Configuration of the Supreme Court

The Court chamber is divided into several sections. (On the ground floor of the Supreme Court is a to-scale diorama that, more or less, accurately represents the current configuration of the Court.)

The Justices sit on the angled bench. The Clerk sits to the left of the bench. The Marshal sits to the right of the bench. Counsel for the parties sit at the first row of tables, right in front of the bench. Generally, each side brings three or four attorneys. The arguing attorney stands in front of the lectern. (Do not try to adjust it during argument!) The second row of tables in front of the bench is reserved for other attorneys.

The press sit on the left side of the Court, in the red seats in front of the columns. Members with "hard passes" have reserved seats. Other members of the media can request access on a case-by-case basis. Reporters without reserved seats will sit behind the columns on the left side of the Court. The red seats on the right side of the Court are reserved for guests of the Justices. There are plaques installed on the seats with each Justice's name. The law clerks sit on the far right side of the Court, behind the columns.

Members of the Supreme Court bar sit in front of the brass bar in the middle of the Court. The diorama depicts ten rows of ten seats. I only observed eight rows of ten seats. There are also six chairs on the left side of the Court. I'll call it 86 seats in the bar section. (I welcome corrections if others have precise numbers).

The general public sits behind the bar. There are 15 benches, each seats 7 people. Generally, one chair is added in the aisle next to each bench. I'll call it 120 seats. (Again, I welcome corrections for precise numbers.)

The Court also allows people to sit in the back of the chamber for three minutes to watch parts of the oral argument. After the three minutes are up, other people will cycle through.

Obtaining a publicly-available seat

The Supreme Court does not sell tickets. Generally, the Court reserves at least 50 seats for each argument day for the general public. (The total number of general admission tickets will depend on how many other seats are reserved.) People who want to attend oral arguments form a line along First Street that snakes around East Capitol Street NE. For high-profile cases, the line can form several days in advance. These brave souls have to endure the elements. Before the DACA case, people huddled under tarps to stay dry during the rain. Around 7:00 a.m., the Supreme Court will issue golden tickets, numbered 1 through 50, to the first 50 people in line. Those tickets will generally guarantee admission to the argument. Those who are beyond #50 may be able to attend argument if any seats remain vacant. They may also be able to cycle through, and watch three minutes of oral arguments.

The Supreme Court does not sell tickets. Generally, the Court reserves at least 50 seats for each argument day for the general public. (The total number of general admission tickets will depend on how many other seats are reserved.) People who want to attend oral arguments form a line along First Street that snakes around East Capitol Street NE. For high-profile cases, the line can form several days in advance. These brave souls have to endure the elements. Before the DACA case, people huddled under tarps to stay dry during the rain. Around 7:00 a.m., the Supreme Court will issue golden tickets, numbered 1 through 50, to the first 50 people in line. Those tickets will generally guarantee admission to the argument. Those who are beyond #50 may be able to attend argument if any seats remain vacant. They may also be able to cycle through, and watch three minutes of oral arguments.

Before I was admitted to the Supreme Court Bar, I waited on the public line a handful of times. Perhaps my longest wait came in 2010 for McDonald v. Chicago. I arrived the night before around 9:00 p.m. When I got on the line, I was #40 or so. The following morning, however, I was #48 or so. About eight people cut in front of me by the dawn's early light. In some cases, paid line waiters would save several spaces. In other cases, people snuck in when no one was looking. The Supreme Court police refuse to monitor the line, and will not intervene if people cut. (More on cutting later.)

After clearing security, those with golden tickets can wait in the cafeteria or check out the Supreme Court's exhibits. Or (in my case) go to a friend's house nearby and grab a shower. So long as they are back to the Court around 8:30, they will be allowed to enter.

Obtaining a reserved seat

There are several ways to obtain a reserved seat.

First, each Justice has a designated number of tickets they can give away. This process is as opaque as it sounds. As they say, you have to know someone.

Second, counsel of the parties receive a certain number of seats for guests. This number will vary depending on how many empty seats there are. Guests who are members of the Supreme Court bar can sit in the bar section. Non-attorney guests can sit in the public section. In consolidated cases with several parties, counsel will have fewer tickets.

Third, parties participating in bar admissions will also receive reserved seating. Attorneys who are members of the highest court of their state for three years can apply for admission to the Supreme Court bar. Applicants have to contact the clerk well in advance. Generally, at the start of each session, the Court will hear several motions for admission. One attorney will rise, and state the names of the members he or she is seeking to admit. After all the names are called, the Chief Justice will ask the inductees to rise, and take the oath. The entire process takes a few minutes, depending on how many people are seeking admission.

On argument days, the Court hears several "small group admissions" (up to 12 applicants). Often, a few small groups are allowed to move for admission on a single day. For example, during the DACA arguments, three attorneys moved for the admission of about 25 members. On non-argument days, the Court hears "large group admissions" (up to 50 applicants). Each person seeking admission is allowed to bring one guest, who sits in the public section.

Many of the bar admissions are scheduled months in advance, to permit the inductees sufficient time to make travel arrangements. But there is another, lesser-known way to attend argument in a specific case. Attorneys can ask the Clerk to schedule a bar admission when a specific case is being argued. The moving attorney, and the attorney taking the oath, are both guaranteed seating in the bar section. I am familiar with this approach, because I employed it in 2016 to attend oral arguments in Zubik v. Burwell. (Ilya Shapiro moved for my admission; the Chief, perhaps against better judgment, granted the motion.)

Obtain a seat in the bar section

Members of the Supreme Court bar, who are not counsel in a given case, and do not have a reserved seat, can also wait on the bar line. This line generally forms on the left side of First Street, and snakes towards Maryland Ave NE. In 2015, the Court prohibited paid line waiters on the bar line. (Lawyers are still saving spots on line; more on that problem later.)

The bar line operates very differently than the public line. First, on the public line, there are 50 guaranteed seats. On the bar line, the number of reserved seats depends on how many seats are reserved for bar admission and for co-counsel. Second, on the public line, Court personnel hand out numbered tickets, so people can easily lay claim to their spot. On the bar line, no tickets are issued. Rather, members of the bar line are asked to enter the Court, go through security, and form another line on the ground floor. At that point, personnel check IDs (to make sure the lawyer is admitted to the bar), and then hands them a numbered ticket. (The process of entering the Court and clearing security creates many, many opportunities for the ordering of the line to change.)

Third, if members of the general public do not secure a seat, they are out of luck. But members of the bar are only partially out of luck. They can sit in the lawyers lounge, and listen to a live-feed of the audio. By my (rough) count, there are about 100 seats in the lawyers lounge. For the DACA case, every seat was full. I heard that during the same-sex marriage cases, there was standing room only. As a result, members of the bar will generally be able to listen, but not see a case being argued.

Summary

Unless you know someone, the only guaranteed way to attend an oral argument is to be one of the first 50 people on the line. And to be really sure, you should stand as close as possible to the front to account for line cutters. If you are a member of the bar, your position is far more uncertain, because the number of available seats depends on how many attorneys are seeking admission in a given day. But, if you are able to obtain a reserved seat, you do not have to worry about these variables.

The next post in this series will explain my experiences during the line for the DACA case. The third post in this series will offer some suggestions to improve the process.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

2nd sentence beneath the first photo needs attention.

Thanks

Thanks to you for all the great history of the Supreme Court.

Not quite right to say that the second row of seats/tables are reserved for other attorneys. On mornings when there are 2 oral arguments, the second row is where the attorneys for the second case sit. At the end of the first argument, the attorneys for the second case then move up to the first row of tables. The attorneys for the first case either leave the courtroom, or can sit at the now-empty second set of tables if they want to stay for the second argument.

It must be so incredible watching arguments before SCOTUS. I really wish they would televise them, or video-record for posterity. I know there are audiotapes, but there is something to facial expressions, or interactions between justices.

Back in the 2004-2007 I was able to go all the time. By 2010 I found paid line-sitters were arriving well before 5am.

It can be tricky as a member of the public.

But it is really cool. Breyer and Thomas passing notes and snickering were my best memories.

In my view a state does not have to find religious schools. But if it does, it cannot fund only those religions whose doctrines or membership policies it likes. Doing so would be an establishment of religion.

Town of Greece V. Galloway introduced a potential sea change in the law here. Previously, when government funded religious speech, the speech was regarded as the government‘a and courts supported monitoring it to ensure nothing inappropriate for governments was said.

Town of Greece reversed this, saying the speech is the religion’s, and government cannot interfere with it because interference would represent establishment.

Accordingly, under Town of Greece, government cannot use funding to coerce religious denominations into changing what they teach or to whom they teach it. Either it finds all religions equally, ones it likes and ones it doesn’t like, or it finds none.

Government can insure students of religious schools are taught skills like how to read, write, and do math. But it cannot dictate what kind of books they read, or what is taught in them.

Sir, this is an Arby’s.

I am very surprised that line-jumping is not policed and paid line-sitting not banned. The court seems to be putting its imprimatur behind the idea that all citizens are equal, but some citizens are more equal than others.

The sign says Equal Justice Under Law. Says nothing about Equal Chance of a Seat.

I think the simpler explanation is, the Court does some extra policing of the bar line because its members are officers of the Court and therefore can be overseen more closely, but it does not in the public line where there's no official relationship.

I think also, given people do need to leave on occasion to use the bathroom and the line, a flat-line "you cannot leave ever" is unworkable. And actively policing without that sort of bright-line rule is going to be very, very difficult.

If only someone would invent a technology that could stream LIVE images and audio! The public could actually see what is going on in the court then! But too bad that hasn't been invented yet. And I have a feeling that when it is, people would make silly arguments about how the public should be permitted to view something so important.

On another note, thanks for this article. Me and my wife are looking to attend any oral argument next year, so this is real helpful.

It has been invented - it just hasn't reached the technologically backward south. Here in Canada, Supreme Court arguments are webcast: https://www.scc-csc.ca/case-dossier/info/hear-aud-eng.aspx

If such a technology were invented, there is a grave risk of the content being very low quality and full of people who were more interested in just being seen by others than actually doing anything of real value. Therefore it would be risky to use that technology to transmit Supreme Court proceedings.

Those who can read a legal opinion should do so. Those who cannot might find it more enjoyable to view the consequences of a random group of people being left on an island or marrying someone they just met.

Video can lead to grandstanding. This is even worse than standing in line.

I don't think I see a witness stand. Where do witnesses testify? Yes, I know, there are generally no witnesses, but in cases in which the Court has original jurisdiction there is no record - do there not arise situations in which witnesses are required?

They appoint a special master to take evidence when it's necessary. That appointment does not include the use of the Supreme Court courtroom.

I guess the guys that do this get beaten up and have their heads flushed by the type that sits in line for days for the latest Star Wars.

So... The best way to attend oral argument is to show up at around 6:58, walk to the front of the line, and grab a ticket. Got it.

16 comments in, and no comments about line-cutters being an issue in the DACA case. I have to say I'm surprised.

The problem is, it's hard to say what line-cutting exists, because there's a custom of people holding each others' places in line to go use the bathroom, get snacks, etc. as needed. It's quite possible someone in the bar line had someone hold their spot while they went north to Union Station to bathrooms. But ultimately, we just don't know here.

As an additional update, if this is with respect to the public line. I was at the Court for the New York gun case a couple weeks ago (and for the Georgia case second that day). The night before, Steven Mazie briefly passed by, and we got to talking with him, and at some point he mentioned that for the DACA case, the DACA folks did a good job mobilizing. They arrived en masse, a fair bit in advance of the argument, then kept up a rotating series of folks temporarily holding positions so that the full public line was DACA recipients. If they successfully executed that strategy, line-cutting is a total non-issue that wouldn't get any discussion here.

Attending oral arguments is always worthwhile if you are in DC and a member of the Supreme Court Bar (the diploma alone is worth the cost).

I wrote an amicus brief on behalf on 18 states back in 2005 and my employer paid for me to travel to DC to watch the argument.

In any event, I watched two days worth of oral arguments. Three things stuck out:

1) Clarence Thomas actually spoke during one of the arguments;

2) Chief Justice Roberts was brand new -- and because Samuel Alito had yet to be confirmed, Sandra Day O'Connor agreed to postpone her own retirement until he was. Thus, we had the Chief Justice sitting with the Justice he was originally nominated to succeed (for those who don't remember. Roberts was tapped for O'Connor's seat. Then Rehnquist died. Consequently, his nomination was switched to Chief Justice).

3) I saw the greatest political theater ever the second day I was there. On the docket was FAIR v. Rumsfeld, which challenged the withholding of federal funds to law schools who refused to allow military recruiters on campus (because of the military's then anti-gay policy).

By pure Washington coincidence, the same day FAIR was argued, the entire left side of the attorney's section was filled with Army JAG officers being sworn into the Supreme Court Bar.

Of course it probably helped that the then Supreme Court Clerk, William Suter, was a retired Major General -- and the former acting Judge Advocate General of the United States Army.

I was visiting family in DC during Heller and my wife and I waited over night to get in. I was surprised at how small the room was.

My experience was much different when I was a plaintiff in McDonald. I did not have to camp out, but also it was very different observing someone else's case and your own. It was awe-some in the original usage of "awe".