The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The Affordable Care Act Imposes A Mandate. Not a Choice.

The Structure of NFIB v. Sebelius: Parts III.A, III.B, III.C, and III.D

On July 9, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral argument in Texas v. United States. The three members on the panel were Judges Jennifer Walker Elrod, Kurt D. Engelhardt, and Carolyn Dineen King. You can listen here.

In my first post, I considered the arguments presented concerning standing. In this post, I will focus on the arguments presented concerning whether the individual mandate is constitutional.

California (represented by Samuel Siegel) and the House of Representatives (represented by Douglas Letter) did not contend that the ACA's individual mandate could be supported by Congress's powers under the Commerce and Necessary and Proper Clauses. Nor could they. That result was foreclosed by NFIB. Judge Elrod's question (at 13:36) raised this point:

"Do you agree that we are not at liberty to uphold this [mandate] based on the commerce or necessary and proper clause, given that there are five votes on the Court against those propositions?"

She's right. Five Justices in NFIB expressly rejected that position.

Rather, the intervenors argued that the ACA does not impose a requirement to buy insurance; to the contrary, the law gave covered individuals a choice between purchasing insurance and paying a modest, non-coercive tax. In other words, it is irrelevant whether Congress has the power to enact a mandate to purchase insurance, because Congress did not enact such a mandate. (Professor Marty Lederman summarizes this position in a post, aptly titled "There is no 'mandate.'") Therefore, it is completely irrelevant what Congress did with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The "choice" architecture has remained constant. Before 2018, people had a choice: buy insurance or pay a tax of approximately $700. After 2018, the alternate choice became paying a tax of $0.

Douglas Letter articulated this position during the oral arguments:

Letter: The Supreme Court majority [in NFIB] said there is a choice. You either shall maintain insurance or you shall pay this tax penalty. [Through the 2017 TCJA,] Congress has now said, we don't want there to be any tax penalty. We want the American people to continue having a choice.

Indeed, Letter argued that this reading was the only permissible reading of NFIB:

Letter: With the proper respect here, you must rule this way because the Supreme court told us in NFIB what the statute means and in 2017 Congress said what it meant in the text and we know.

His reading of NFIB is a common one. Indeed, I have encountered it numerous times over the past seven years while teaching and writing about NFIB. Respectfully, it is an incorrect reading. Chief Justice Roberts only accepted the "choice" argument as part of the saving construction in Part III.C of his controlling opinion. However, that portion of his opinion is no longer controlling because Section 5000A can no longer be reasonably read as imposing a tax. Why? The penalty, which was reduced to $0, now raises no revenue. Part III.A, which held that the "most natural" reading of Section 5000A--imposing an unconstitutional command to buy insurance--is now the controlling opinion.

To understand why Part III.C is no longer controlling, and why the choice architecture has crumbled, we need to take a stroll down memory lane. This post will quote at some length from my 2013 book, Unprecedented. I do so to demonstrate that the injury-in-fact debate in Texas is not new. It was resolved seven years ago.

I agree with Chief Justice Roberts that Section 5000A "reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance than [offering people a choice to pay] . . . a tax." As a threshold matter, the notion that Section 5000A did not impose a mandate, but merely offered people a "choice" was manufactured at some point after the ACA was enacted. This argument was not made, publicly at least, while the law was being debated in 2009 and 2010.

During oral arguments, Judge Engeldhardt posed this question to Samuel Siegel, the lawyer for California (at 19:36):

Judge Engelhardt: Where are the statements from those who voted in 2010 saying, no worries, the individual mandate isn't really a mandate? Even though it says shall, we are voting on it today, and citizens, this is an option, you can pay a tax, or you can buy the insurance… Where are the statements from 2010, saying don't worry about the individual mandate, it's actually not something that requires you to buy insurance.

California: I don't know where those statements might be.

While writing Unprecedented, I searched the legislative history of the ACA to find support for the contention that Section 5000A imposed a "choice," rather than a mandate. I couldn't find anything. (I do not think the existence of such legislative history is necessary to resolve this question, but there are those who do find it useful.) I posed the same question to the ACA's most ardent defenders, including Obama administration officials. They could point to nothing. I remain open to being persuaded otherwise, if anyone can point to any contemporaneous discussion from before March 2010 advancing the "choice" reading of Section 5000A.

Before the Supreme Court, Solicitor General Verrilli advanced the "choice" argument. This position emerged from Judge Kavanaugh's dissent in Seven-Sky v. Holder. From p. 158 of Unprecedented:

Kavanaugh, however, made a point in passing that was not lost on the solicitor general. A statute similar to the one Congress enacted, but without the individual mandate, said the judge, would be absolutely constitutional. Kavanaugh reasoned that a "minor tweak to the current statutory language would definitively establish the law's constitutionality under the Taxing Clause (and thereby moot any need to consider the Commerce Clause)." By "eliminat[ing] the legal mandate language"—that is, by deleting a single sentence—the statute would be transformed from a command on people to purchase insurance to a mere tax on those who do not have insurance. The former was of dubious constitutionality, but the latter would be well within Congress's powers. Kavanaugh was echoing Justice Stone's whisper to Frances Perkins, "The taxing power of the Federal Government, my dear, the taxing power is sufficient for everything you want and need." Like Frances Perkins before him, the solicitor general listened carefully. Simply eliminating one sentence—the mandate—would save the law. With an assist from Judge Kavanaugh, the solicitor general advanced this very argument at the Supreme Court.

(You can read the entire chapter here.)

After Judge Kavanaugh's opinion, I noted, the government's thinking shifted (at p. 163):

The decision to take a second look at the taxing power came from the top. One reporter who covers the Supreme Court told me that Verrilli personally "insisted on pushing" it. Of course, the "obvious problem" was that the word "tax" was not in the individual mandate provision. The word used was "penalty." "Apart from that," I was told by a senior DOJ official with no irony, that the tax argument "had a lot going for it." Judge Kavanaugh's opinion convinced the Solicitor General's office that the "tax argument might be a more conservative and judicially restrained basis to act to uphold as a tax." The "nomenclature was the only serious impediment to winning." Despite this problem, the solicitor general believed that characterizing the mandate as a choice between maintaining insurance and paying a tax was not only a way of avoiding a serious constitutional question, but indeed the best reading of the law. Though it "wasn't ideal," the government determined that it "could manage" this argument. And the key to solving that problem of nomenclature fell directly on the shoulders of Donald Verrilli, with Judge Kavanaugh being credited with the "assist."

The choice argument is not new. Solicitor General Verrilli advanced this argument to the Supreme Court in 2012 (at p. 179):

Verrilli pushed back against any questions about the mandate and rejected any assertions that it was an "entirely stand-alone" requirement to buy insurance. As the government noted in its brief, citing the opinion of Judge Kavanaugh from the D.C. Circuit,"To the extent the constitutionality of [the act] depends on whether [the minimum coverage provision] creates an independent legal obligation [a mandate], the Court should construe it not to do so." In other words, in order to save the ACA, the Court should read the mandate to not be an actual mandate

Here is how Verrilli articulated the position in his brief:

Even in Judge Kavanaugh's view, however, a "minor tweak to the current statutory language would definitively establish the law's constitutionality under the Taxing Clause." Seven-Sky, 661 F.3d at 48. He suggested, for example, that Congress might retain the exactions and payment amounts as they are but eliminate the legal mandate language in Section 5000A, instead providing some- thing to the effect of: "An applicable individual without minimum essential coverage must make a payment to the IRS on his or her tax return in the amounts listed in Section 5000A(c)." Id. at 49.

In fact, no "minor tweak to the current statutory language" (Seven-Sky, 661 F.3d at 48 (Kavanaugh, dissenting)) is required because Section 5000A as currently drafted is materially indistinguishable from Judge Kavanaugh's proposed revision. Statutory provisions "must be read in * * * context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme." FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 133 (2000) (quoting Davis v. Michigan Dep't of the Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)). When understood as an exercise of Congress's power over taxation and read in the context of Section 5000A as a whole, subsection (a) serves only as the predicate for tax consequences imposed by the rest of the section. It serves no other purpose in the statutory scheme. Section 5000A imposes no consequence other than a tax penalty for a taxpayer's failure to maintain minimum coverage, and it thus establishes no independently enforceable legal obligation..

Had the Supreme Court accepted Verrilli's argument, and found that "Section 5000A as currently drafted is materially indistinguishable from Judge Kavanaugh's proposed revision," then the mandate challenge in Texas v. United States would be without merit: the plaintiffs cannot challenge the individual mandate because there is no individual mandate! Letter and Lederman advanced this position. But the Court did not make such a holding. We know the Court did not make this holding because of the structure of Part III.A, III.B, III.C, and III.D of Chief Justice Roberts's controlling opinion.

I offered the following description of this structure on pp. 9-11 of my article, Undone (which was cited by Judge O'Connor):

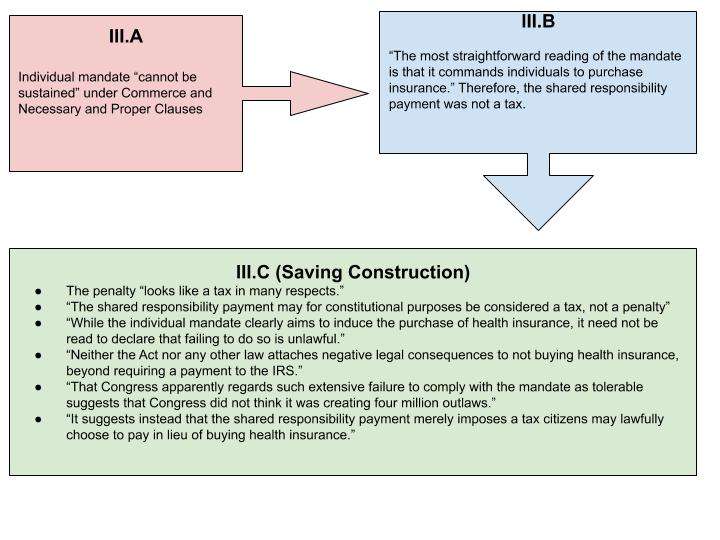

In Part III.A.1, the Chief Justice found that the individual mandate "cannot be sustained under a clause authorizing Congress to 'regulate Commerce.'" In Part III.A.2, the Chief Justice concluded that the mandate cannot be "upheld as a 'necessary and proper' component of the insurance reforms." That is, Congress could not mandate that people purchase insurance in order to implement the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions—the guards against adverse selection. However, "[t]hat [was] not the end of the matter."

In Part III.B, the Chief Justice considered if "the mandate may be upheld as within Congress's enumerated power to 'lay and collect Taxes.'" He posited that "if the mandate is in effect just a tax hike on certain taxpayers who do not have health insurance, it may be within Congress's constitutional power to tax." Yet, he rejected that conclusion: "The most straightforward reading of the mandate is that it commands individuals to purchase insurance." Therefore, the shared responsibility payment was not a tax. Still, that observation was not the end of the matter.

In Part III.C., the Chief Justice developed the so-called "saving construction." He explained that "[t]he exaction the Affordable Care Act imposes on those without health insurance"—that is, the penalty that was not actually a tax—"looks like a tax in many respects." The Chief Justice then listed three guardrails in which the "exaction"—that is, the shared responsibility payment—can be construed as a tax. First, "[t]he '[s]hared responsibility payment,' as the statute entitles it, is paid into the Treasury by 'taxpayer[s]' when they file their tax returns." Second, "[f]or taxpayers who do owe the payment, its amount is determined by such familiar factors as taxable income, number of dependents, and joint filing status." Third, "[t]his process" of making the payments, "yields the essential feature of any tax: It produces at least some revenue for the Government. . . . Indeed, the payment is expected to raise about $4 billion per year by 2017." These three guardrails are essential to the saving construction.

Finally, the controlling opinion acknowledged that the shared responsibility payment can still be saved as a tax, despite the fact that it was primarily designed to "affect individual conduct," not to raise revenue. However, that design cannot be achieved unless, in the first instance, the payment can be saved as a tax. Why? All of the exactions cited by the Chief Justice raised revenue as the means to "affect individual conduct." In other words, people modified their conduct to avoid having to pay extra money to the government. For example, "federal and state taxes can compose more than half the retail price of cigarettes, not just to raise more money, but to encourage people to quit smoking." Some people will quit smoking to avoid having to pay the taxes, but even those who continue smoking will pay the tax. But Congress must have the power to enact the exaction in the first place. Critically, Justice Ginsburg, as well as Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, joined Part III–C of the Chief Justice's opinion. As a result, there were five votes for the proposition that the individual mandate could be upheld as an exercise of Congress's Taxing Power.

I've created a diagram to explain Part III of Chief Justice Roberts's controlling opinion.

During oral argument, Texas Solicitor General Kyle Hawkins concisely explained why Part III.A is the only relevant portion of NFIB; parts III.B and III.C are now irrelevant: (starting at 56:36)

Hawkins: My friend Mr. Letter is seriously misreading the Supreme Court's decision in NFIB. NFIB holds that the individual mandate is unlawful. It holds that 5000A(a) is best read as a command to buy insurance. And it held that that command, despite being unlawful, can only be saved if it is fairly possible to read the law as a tax. It follows, if the law cannot fairly be read as a tax, then the original holding stands and the mandate is unlawful. I think it is crucial to understand the structure of Chief Justice Roberts opinion to see how he gets there. In Part III.A of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion, he looks at the mandate. Only the mandate. Not the penalty. He says that the best way to read that is as a command to buy insurance. And then he says two things about it… That it's a command to buy insurance. And two, that command cannot be justified by the Commerce Clause or by the Necessary and Proper Clause. That's the end of III.A. He then shifts gears. In III.B and III.C of his opinion, where he says, given our holding in Part III.A we need to determine whether there is some way to save the individual mandate. And that's what he finds out in III.B and III.C is that given the fact that there is a penalty provision, and given that the penalty is raising revenue for the government, he says that we can glue the individual mandate provision to the penalty provision, and once they are glued together, then they function as a tax. Such that the law can be saved by construing it as a tax, and that tax is available under the federal government's taxing power. Now what happened in 2017 is Congress took away everything that supported III.B and III.C of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion. This [penalty] is no longer raising any revenue for the federal government. It no longer can be fairly characterized as a tax. So in light of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Part III.B and IIII.C of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion are irrelevant. The only thing we are left with then is Part III.A of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion, where he holds that is a command to buy insurance.

At that point, Judge Elrod asked if the court should "sever" Parts III.B and III.C from NFIB. Exactly! I framed the analysis this way in Undone:

Therefore, the predicate of Part III.C of the controlling opinion in NFIB is no longer relevant. Or, to put it differently, Part III.C has now been severed from the opinion.

Virtually every critic of Texas treats Part III.C as controlling. It isn't. Indeed, all of Chief Justice Roberts's observations in Part III.C were hedged, offered as conditional statements. For example:

- "While the individual mandate clearly aims to induce the purchase of health insurance, it need not be read to declare that failing to do so is unlawful."

- "That Congress apparently regards such extensive failure to comply with the mandate as tolerable suggests that Congress did not think it was creating four million outlaws."

- "It suggests instead that the shared responsibility payment merely imposes a tax citizens may lawfully choose to pay in lieu of buying health insurance."

None of these statements are premised on the best reading of the ACA; rather, they can only be supported in light of the saving construction; a construction that is no longer permissible. Part III.A held that the mandate was unconstitutional. Section 5000A was only saved by virtue of that saving construction.(I am perplexed by co-blogger Jonathan Adler's assertion that Randy and I argued that the mandate was somehow "resuscitated" by the 2017 tax bill. Zeroing out the penalty in no way affected the mandate, which was a separate statutory provision. Indeed, we made the exact opposite claim: the mandate has been unconstitutional since 2012.)

Hawkins offered this explanation:

Hawkins: Your honor, I think we read the Supreme Court's opinion fairly in light of subsequent events. It is crucial to do so here. The entire basis for III.B and III.C is now off the table. Now Chief Justice Roberts in IIIA holds that this is a command, not justifiable. That is fully supported by the four dissenting Justices. There is no doubt, there were five votes, that it is a command not justifiable by the commerce power or necessary and proper clause.

Perhaps you don't believe me. Maybe you argue that this reading of NFIB is incorrect, and that Part III.C is still the holding, regardless of the saving construction. If so, look no further than Part III.D of NFIB. It is only two paragraphs, but Chief Justice Roberts explains the structure of his own opinion:

Justice Ginsburg questions the necessity of rejecting the Government's commerce power argument, given that §5000A can be upheld under the taxing power. But the statute reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance than as a tax, and I would uphold it as a command if the Constitution allowed it. It is only because the Commerce Clause does not authorize such a command that it is necessary to reach the taxing power question. And it is only because we have a duty to construe a statute to save it, if fairly possible, that §5000A can be interpreted as a tax. Without deciding the Commerce Clause question, I would find no basis to adopt such a saving construction. The Federal Government does not have the power to order people to buy health insurance. Section 5000A would therefore be unconstitutional if read as a command. The Federal Government does have the power to impose a tax on those without health insurance. Section 5000A is therefore constitutional, because it can reasonably be read as a tax.

Section 5000A can no longer "reasonably be read as a tax." Therefore, we are left with a statute that "reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance." And "[t]he Federal Government does not have the power to order people to buy health insurance." As a result, Section 5000A(a) is now unconstitutional because it "read[s] as a command."

Part III.C of NFIB saved Section 5000A as a whole--with the mandate and penalty glued together as a "tax" on going uninsured. That opinion did not hold that the mandate (Section 5000A(a)), in particular, was constitutional. Kyle Hawkins, the Texas Solicitor General, explained this premise during oral argument:

Hawkins: The best evidence that I'm right about this is Justice GInsburg's dissent. In dissent she faults Chief Justice Roberts for discussing the commerce clause, for reaching the commerce clause holding. Justice Ginsburg said, look, this is obviously is a tax, and just say that it is a tax and be done with it. We don't have to say anything about the commerce clause. But Chief Justice Roberts rejected that. And this is in Part III.D of his opinion. He responds to Justice Ginsburg III.D and he says, no, I have to reach a commerce clause holding because this is best read as a command to buy insurance. So I have … to give it the best reading possible. Then I have to assess whether that best reading is constitutional or not. And only after doing that analysis, then do I get to the taxing issue. I think that interplay between Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Ginsburg shows that our reading is correct, and the other side's reading is incorrect because it elides the differences between those four different parts of Section III of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion.

At bottom, NFIB held that Section 5000A(a) creates a free-standing obligation. That obligation was unconstitutional in 2012. It was unconstitutional in 2017. And it is unconstitutional in 2019. Section 5000A(a) could be read as offering a "choice" to taxpayers from 2012 through 2017. Chief Justice Roberts reached this conclusion, as did then-Judge Kavanaugh. But Section 5000A(a) can no longer be read that way. Now, under the reasoning of both Roberts and Kavanaugh, plus that of the remaining joint-dissenters (Justices Thomas and Alito), Section 5000A(a) imposes an unconstitutional command to buy insurance.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Congress is entitled to decorate its chambers and its statute books with whatever art it cares to. It can open its sessions with whatever invocations it wants, including prayers. It can give the American public whatever advice about how to live their lives it cares to give them. And all of this is no business whatsoever of the federal courts.

Perhaps the classic explanation of what federal courts need to do when a legislature makes something illegal with no enforcement is in Doe v. Duling, 787 F.2nd 1202, a 4th Circuit case involving a challenge to a Virginia fornication statute. The 4th Circuit said that unless the plaintiffs could show a credible threat of prosecution or other concrete consequence of their breaking the law, how the Virginia legislature chooses to decorate its statute books is simply none of the Federal courts’ concern. The plaintiff’s subjective desire to be law-abiding and subjective dislike of the law simply doesn’t give rise to Article III standing.

Absent concrete consequences, it isn’t a tax. It isn’t a penalty. It isn’t a mandate. It’s advice.

In Deep Space Nine, the author of the Ferengi Laws of Acquisition revealed that he gave the book its title as a marketing ploy. Who would buy a book called the Suggestions of Acquisition?

This is similar. Calling it a mandate is nothing more than puffery. It too is a marketing ploy. There is no justiciable case or controversy, and no Article III standing.

Absent concrete consequences, it isn’t a tax. It isn’t a penalty. It isn’t a mandate. It’s advice.

Up to a point, Lord Copper. There's a very faint, and very complicated echo in the legal shenanigans currently going on in the trial of General Flynn's business partner. The structure of the government's legal argument seems to be roughly as follows :

Law A says "you can't do X" and "in order to be punished under this law, you have to do it willfully."

Law B says "you can be punished if you do Y, unless that something is a legal commercial transaction under Law A"

The government argues that doing the particular Y that was done was also an X. And that doing an X is not a legal transaction under Law A even if it is not done wilfully. Hence you can be convicted under Law B even though you can't be convicted under Law A, because what you did was unlawful under Law A (though not punishable under Law A - because not wilful.)

Thus it's possible to have a sort of Schrodinger's Cat illegality which remains merely potential until it runs into another Statute that says you mustn't have done anything illegal under some other law, and which carries a punishment if you did.

I can't even make sense of what you're trying to say. My best guess is you think someone, someday, might be subject to government action under the mandate (lacking any penalty). If so, that's the case in which the no-longer-existent mandate should be challenged.

I'm not talking about the mandate at all. I'm questioning Reader Y's general proposition that a legal command which lacks an enforcement mechanism is therefore necessarily inconsequential.

Certainly you'd agree that it isn't sufficiently consequential to implicate a broccoli mandate argument?

Don't forget the Iran Contra prosecutions where Poindexter, McFarlane and North were all convicted of conspiracy for violating the Boland amendment, which was just a prohibition with no penalty.

Any violation of the law can be prosecuted if there is a phone call, mail, or web transaction involved, even a violating law with no penalty can land you behind bars for years.

If you're so sure that criminal implications attach, wait for them to bear fruit and sue based on that real, non-speculative case.

"Don’t forget the Iran Contra prosecutions where Poindexter, McFarlane and North were all convicted of conspiracy for violating the Boland amendment..."

This is not true.

By way of a made-up example, Lee is arguing that you apply for a security clearance but are denied because you broke the law by choosing to not carry insurance when the penalty for doing so is $0. And yes, that would be a good time to challenge whether you had in fact broke the law.

That makes sense. It also has its own issues, since the government's entitlement to withhold security clearances is not based on CC, and so it would still be subject to a savings interpretation.

I would prefer to call it "grossly simpified" rather than "made up" since it is - as I perhaps mistakenly understand it - the actual argument actually being run by the government in the actual (and current) trial of Flynn's business partner.

Flynn's business partner is on trial on something related to not carrying health insurance? Citation?

Which part of "I’m not talking about the mandate at all. I’m questioning Reader Y’s general proposition that a legal command which lacks an enforcement mechanism is therefore necessarily inconsequential" did you find partiularly difficult to understand ?

Well, the law has been in effect for some time during which the government has issued a lot of security clearances. So, as an empirical question, has anyone been denied a clearance for failure to comply with the mandate? (It's been a while, but it was post-ACA, when I last filled out the forms to update my security clearance, and I don't recall any ACA questions. However, I had and have an ACA compliant policy, so I wouldn't have been parsing generally phrased questions to try to determine whether they required reporting mandate non-compliance.)

The business partner was convicted on all counts. Like many traitors, Flynn chose poorly, but he will get a free anti-Mueller t-shirt.

What if you have to certify under oath that you are law-abiding, or otherwise you (or your business) makes promises to abide by all applicable laws. What if you are applying for a government license of some kind and need to assert you follow all laws? Do you count the law that says you have to do X, even if the government can't penalize you for not doing X?

What ifs do not a case or a controversy.

Find someone to whom this applies; let them get before the Court.

I'm not saying this kind of talmudic opinion reading won't work, but it sure has hell shouldn't.

You'd be surprised when these odd laws can be applied.

For example, in 1897, the state of Michigan passed a law making it illegal to curse around women and children.

In 1998, Michigan prosecuted and convicted a person for cursing where women and children could hear him.

Then find a client, if it's so easy.

So, you've got to break the law in order to figure out if it's constitutional? And if an argument is made that it is and is believed... Well, then you go to prison? Not to mention the cost in time, money, and lawyers, regardless.

Seems pretty effective as a deterrent, based on risk alone.

It's nice that you've apparently just learned how Constitutional test cases work.

Frankly, it's a ridiculous way to challenge the Constitutionality of a law. The very fact that a law exists that restricts your freedom to do something should be sufficient standing, without having to take it to the Supreme Court.

So, you’ve got to break the law in order to figure out if it’s constitutional.

Yep, this is indeed how the law works in the US throughout it's history.

"What if you have to certify under oath that you are law-abiding, or otherwise you (or your business) makes promises to abide by all applicable laws."

Did you either carry appropriate insurance OR pay $0 to the federal Treasury when you filed your income taxes? Then you complied with the law. If you didn't carry insurance, OR you didn't pay $0 to the treasury with your taxes, but you did the other one, then you also complied with the law. The only way you didn't comply with the law is if you BOTH didn't carry insurance AND didn't remit $0 to the Treasury have you violated the law.

Congress sometimes sets exceptions to tax rules... like, for example, allowing multi-national corporations to repatriate overseas profits at a 0% tax rate. This doesn't make corporate income tax null and void. Nor does sales tax become null and void because they set a 0% sales tax rate on food.

Say, didn't President Trump say he'd have a "better than Obamacare" healthcare bill ready to sign on "day one"? Whatever happened to that?

So if the federal government says I must buy a Lexus, that is unconstitutional but if they say I must buy either a Lexus or a Ford, that is OK. And if they say that I don't have to buy either, but if I choose not to buy an automobile at all they will tax me $700 per year, that is also OK. Constitutionally. So apparently, according to this argument, it is OK to tax people based on what they choose NOT to do.

Hmm. You can choose to vote for either of the two major parties but if you choose to vote for a smaller party you will be taxed $700?

Interesting. Too bad there isn't a "what the hell business is it of theirs" clause in the Constitution.

At least they are being forced to call it a tax. If you have to pay money to government because your heart is beating, it's a tax.

The alternative, you have to buy something because your heart is beating, goes a step too far.

In reality I am less concerned with this than a single payer system, which is akin to Social Security law outlawing saving money for retirement independently, which is ludicrous.

Republicans are ensuring that universal health care is inevitable in the United States.

Thanks, clingers, for the help.

Universal health care - Medicare for all -

Any way you slice it - it means lower quality healthcare for everyone at greater costs. ACA was just a small step in that direction.

Joe_dallas, what you take as an article of faith is indeed true - if you're upper class.

Below that, it's fine till you're sick. Then it's a war between you, your insurance company, and bankruptcy.

The ACA does not cure that problem, it just makes sure more people are at least covered for the little stuff.

Wrong Sarcastro.

The little stuff is far cheaper to pay cash than pay for insurance especially for younger healthy people. Carrying catastrophic insurance would take care of that issue. However any type of insurance, even Medicaid/Medicare for All, will pile up one's bills after any major treatment.

" any type of insurance, even Medicaid/Medicare for All, will pile up one’s bills after any major treatment."

Whereas not carrying any insurance leaves you entirely free of bills post major treatment. Well, you DO still have to pay your bankruptcy attorney, but other than that... poof!

FlameCCT, Universal healthcare, cited by Joe, is not like that.

Moreover, as James Pollock noted, since the final goal is affordable health care Medicare is a lot better than nothing.

See that report of how many died because states wouldn't extend their Medicaid?

Wasn't there a study that showed that there was no statistical difference between people who had no insurance, and people who had MedicAid?

Why, yes, there was:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oregon_Medicaid_health_experiment

I am currently unemployed. I have no insurance, in no small part because COBRA is so expensive (and it became dramatically more expensive because of ACA -- before ACA, we were able to do COBRA). In a couple of months, my son will go through some rather extensive surgery to correct a birth defect where his foot can twist sideways or even backwards while running -- he has already broken a collar bone running down the hill.

I have also seen firsthand what health care is like in Great Britain. I have seen the health "care" my father-in-law got when he was in the Veteran's Administration. I have also learned that the standard rule of thumb that Native Americans on a reservation near my father-in-law's home is "You should only get sick in the first half of the year" -- and they have government-supplied health care.

I will much rather have this surgery done without insurance, than I would to be in Great Britain, where the surgery would either be considered elective, or my son would have had a significant chance of being on a long waitlist for the surgery.

Having said that, I have to put a shout-out for Shriner's Hospitals, who are willing to do this surgery in a timely manner, send us the bill, and then let us decide how much (if any) of the bill we can pay over time.

(Incidentally, ACA doesn't ensure we're covered for the little stuff. After ACA took effect, a large number of plans essentially became catastrophic with *very* high deductibles, but at a price comparable to *non*-catastrophic plans before ACA.)

"Any way you slice it – it means lower quality healthcare for everyone at greater costs."

It sure is easier to make arguments when all you have to do is state your premise as the conclusion, without bothering with any of that tedious gathering of evidence to support your claim.

If the government is concerned about people's health, perhaps they can stop subsidizing sugar and corn syrup? And if the left is concerned about people's health, perhaps they can put 1/10th the effort the put into socialized medicine into eliminating such subsides?

No thanks to the Democrats, who have been slowly and deliberately sabotaging free market health care over a course of decades.

Yes, free market health care has its problems, but it's better than what the United States has right now, and it's been that way for decades.

(And even though US health care is a shadow of free market health care, even that bit is sufficient to make it considerably better than health "care" you can get around the world.)

"In reality I am less concerned with this than a single payer system, which is akin to Social Security law outlawing saving money for retirement independently, which is ludicrous."

It sure is ludicrous to believe that.

Single-payer insurance in no way prevents you from spending your money on healthcare.

"Single-payer insurance in no way prevents you from spending your money on healthcare."

Really? If I need to see a doctor, and there's a two-month wait, I can pay the doctor, say, an extra $100 to see me sooner?

On the other hand, if you need to see the doctor, and there's a zero-month wait, you can pay the doctor and go right in.

It's nobody's fault but your own that you want to go to the doctor with the two-month wait.

Notice that the tax is explicitly called a penalty.

Penalty Penal retribution; punishment for crime or offense; the suffering in person or property which is annexed by law or judicial decision to the commission of a crime, offense, or trespass.

This is not a tax then but a punishment, indicating that an offense has occurred. We all have this "choice" every day. We can obey the government or be fined and imprisoned.

"the law gave covered individuals a choice between purchasing insurance and paying a modest, non-coercive tax."

You thought you had a "mandate" to obey the law? Not at all! You always have the choice of getting fined and imprisoned. And "non-coercive tax" is an oxymoron.

"Not at all! You always have the choice of getting fined and imprisoned."

You no longer are subject to either a fine or imprisonment for not purchasing health insurance.

This is a dumb argument. Lots of taxes are intended to "punish" "bad behavior". Excise taxes, in general, tend to fall into this category.

Government loves them because they work either way... either people keep buying tobacco, alcohol, or machine guns, or people stop having to deal with so many machine-gun wielding drunken smokers. Win-win

"Imprisoned"? What are you talking about? It never possible to be imprisoned for not carrying insurance. The most the government was permitted to do was to recover assessed penalties from your tax refund. Nothing else.

"Too bad there isn’t a “what the hell business is it of theirs” clause in the Constitution."

Something like this?

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people

Meaningless boilerplate. Transparently, the founding fathers, who had just dug themselves out from under a tyrant king, were interested in makng sure potential future tyrants could grow their power without resorting to constitutional amendment.

Reader Y: The problem that i could see is that a future Congress could raise that tax to anything they wanted and the whole process starts again. Why not resolve the issue and get rid of the decorations?

Why would it start again? The circumstance you are anticipating was resolved in NFIB v. Sebelius.

The problem that i could see is that a future Congress could raise that tax to anything they wanted and the whole process starts again.

So what? A future Congress might do anything. Even if this absurdist argument - the only sensible way to describe it - wins, there is nothing to stop future Congress from passing ACA again, with maybe a $.01 penalty, just to shut Barnett and Blackman up, in its entirety.

This

Congress will enact universal health care. The bitter muttering and complaints about 'all of this damned progress' will continue.

But you don't foresee any progress on the easy things that government can do to improve people's health, like eliminating subsidies on sugar and corn syrup? Perhaps the easy things are unworthy of a government capable of great things like running the nation's health care system?

I sense that ending those subsidies would be a sound act.

And when we get that "universal" health care, actual progress in medical treatment will come to a halt. As it is, all those other countries that have "universal" health care have a ten to twenty year lag between when a treatment is developed in the United States, and when it reaches other countries.

The flow of medical advancements from the United States to the rest of the world is a torrent, but the flow from the rest of the world to the United States is a trickle.

The reason why is that Article III only empowers federal courts to decide “cases or controversies,” which requires a plaintiff to show that the defendant’s conduct has caused them a loss or is in imminent danger of doing so. The Constitution prohibits Federal courts from stepping in to preemptively solve potential future problems or interesting philosophical questions. They don’t have the power to do so.

I've been wondering:

Generally academics work on issues that they think are interesting and/or important. That's why political ideology correlates with academic fields, and with working in academia in the first place. But what's so interesting or important about taking away poor people's health insurance?

I mean, it's one thing to work as a shill for the "taxes should always be lower"-people in some kind of think tank, because that's the only job you can get that doesn't involve flipping burgers. But if you're a legit academic, and you presumably have a degree of choice as to which issues to work on, what's the attraction of this one?

Why would you agree to defend someone you're confident he's guilty ? After all, the guy should be in jail.

Maybe you think the rule of law is a good thing and that the government should have to play by the rules too. Maybe even if you don't think this as a matter of principle, you think it from a consequentialist point of view - ie governments that become confident that they don't have to play by the rules may become rather disagreeable.

Perhaps it's just a matter of imagination. Perhaps some folk just can't imagine the government being run by folk who don't think like themselves. Though after 8 years of Obama and two and a half of Trump, I'm assuming most of those folk have been trapped in a deep mineshaft for the last decade. How're you finding it down there, btw ?

Do not mix up is an ought. This is an advocacy piece arguing that the law should read like this; it is not a descriptive piece.

That is sophistry on steroids. Blackman is describing the way he thinks the law should correctly be read. Obviously by so doing he is advocating that the judges should read it so.

Any piece by anybody arguing that the law means this or that will include both "is" - this "is" the legally correct reading; and "ought" - the judges "ought" to apply the correct legal reading.

Describing how the law "ought" to be read in order for the reading to be legally correct is not an "ought" statement in the Humean sense, anymore than is describing how Knob A "ought" to be adjusted to get the camera into focus for a picture at range X.

Put another and more factual way: Blackamn writes against the ACA and health care because he doesn't like the ACA and health care. Anything else is sophistry.

Did you read the OP? It's not about what the law ought to be, it's an argument about what the law is.

But it's an argument, it's not a description.

Sophistry. Sheesh.

I agree it’s appropriate for a law professor to say what the law requires even if what it requires is not what others may consider the right thing to do. I simply disagree with Professor Blackman on what the law requires in this instance.

Maybe you think the rule of law is a good thing and that the government should have to play by the rules too.

Which they are in fact doing. The Blackman/Barnett argument is an ego-driven exercise in absurd legal sophistry, put at the service of people who can't stand the idea that poor people can have health insurance.

Which they are in fact doing.

Plainly Blackman disagrees.

Lee,

I suspect there are ample opportunities for lawyers interested in forcing the government to obey the law to act on that interest, in ways that actually accomplish some good.

Aside from the fact that I consider their whole argument a joke, I also have a certain amount of contempt for them for using their talents to promote it. I don't know what their motivations are, but it's hard to think of one that's admirable.

Let me be clear. I thought the anti-mandate arguments in NFIB were wrong, but OK. I can buy that they had some sort of legitimate basis. Not so, here.

Of course he does; but so what?

So....do you think Blackman would like the government to stick within the rules as Blackman understands them to be, or within the rules as bernard understands them to be ?

And for that matter do you think bernard would like the government to stick within the rules as he sees them, or the rules as Blackman sees them ?

"So….do you think Blackman would like the government to stick within the rules as Blackman understands them to be, or within the rules as bernard understands them to be ?"

I think Blackman would prefer the government work the way Blackman would prefer it to work. That's fairly circular.

However, I have no reason to engage in the sort of wishful thinking that Prof Blackman does.

"Why would you agree to defend someone you’re confident he’s guilty ?'

99%+ of the population wouldn't, and doesn't.

"Maybe you think the rule of law is a good thing and that the government should have to play by the rules too."

Maybe I think the government did play by the rules.

Still, there is at least a bit of entertainment watching this approach to resolve not having enough interest to participate in the ACA legislation, and then listening to the same people who support this approach whining about the D's "obstruction" of Trump's border wall. They won't vote to give him a few billion dollars of useless wall, and they (gasp!) turn to the courts to stop him from twisting other appropriations to use them for the boondoggle.

Libertarian idealists, like any ideology, need to believe that there is some justice in healthcare being tied to needing to strive for it. And that a society that privileges liberty (as they define it) is a good and driver of other good things above and beyond this particular janky healthcare system.

In other words, you can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs.

"But what’s so interesting or important about taking away poor people’s health insurance?"

I know, right? Why mess with somebody else's free lunch?

The trouble is the criticism here is not that ACA is bad policy and ought to be repealed and replaced with one of the wondrous plans Trump and the GOP keep advertising, and never deliver, or even describe.

It's that if you twist yourself into a pretzel and squint through some funny glasses, and ignore logic, why then it's unconstitutional.

"It’s that if you twist yourself into a pretzel and squint through some funny glasses, and ignore logic, why then it’s unconstitutional."

Yeah, the left never does that. I was responding directly to a comment wondering why Academics "want to take away people's health insurance". But of course this is the problem with the free lunch mentality.

The problem with your "free lunch" deal is that it's nonsense. Revert to the pre-ACA healthcare system, and hospitals are required to treat people who need life-saving treatment whether they can pay for it or not. That's TOTALLY different, right?

Hospitals are required to treat people, even under the ACA. What we ought to do is get rid if the ACA, and make health care tax deductible. That way we eliminate employer-provided health insurance, and create a free market.

Now you don't want employers providing healthcare, either? You really DO want to take healthcare away from people.

Just because you lost the argument in Europe decades ago about the government being able to tell you what you can and cannot say, or what you must do when the government tell you to, doesn't mean we have to all throw in the towel the way you did.

What absolute sophistry. Whether something is a mandate--or not--has to do with coercion, not mere words. Of course there would be no reason for the CJ to mention the penalty in III-A, since it was undisputed that there was, in fact, a penalty. The government was certainly focused on the penalty to prove up the mandate for CC purposes.

You're reading of III-B is aggressive as well. III-B does not conclude that it is a mandate (rather than a tax). You've cherry picked one portion of that section, which concludes with "it can be so read" (as a tax).

Anyway, this is all irrelevant. A mandate with no penalty is subject to the same savings construction that a mandate with a tax is. SCOTUS is not bound by III-A. The saving reading now is that there being no enforcement mechanism, there can be no mandate. Without a mandate, there is no commerce clause problem.

AAAHAHHHHH "You're". I hate myself so much.

I didn't react to reading "You're reading" because, at the time, I was.

PRECISELY AS INTENDED.

Just blame it on the spellchecker and move on. Half my typos these days I typed it right and the spellchecker auto corrected it to some other word.

The spellchecker can be a useful personal assistant cleaning up your mistakes, but for the most part I don't see it as my responsibility to loop back and clean up the spellchecker's mistakes. Who is in charge here anyway?

"Whether something is a mandate–or not–has to do with coercion, not mere words."

I don't now if that's true. Most people understand the difference between, say, and entry fee for a national park, and a fine or trespassing, even if the fine and the fee are the same.

"Whether something is a mandate–or not–has to do with coercion, not mere words."

I don't now if that's true. Most people understand the difference between, say, and entry fee for a national park, and a fine or trespassing, even if the fine and the fee are the same.

Fees for entering national parks are $0 for fourth-graders, and they have "free weekends" from time to time when it's $0 for everybody. Guess it's unconstitutional because it's not raising any revenue...

These articles on Texas v. United States call to mind a now-familiar movie trope. Someone people care about—someone brilliant—has been acting strange. He stiff-arms attempts to converse. He seems to be getting worse. He's been avoiding people during the day. He goes out only in the small hours of the morning, to bring back takeout from some all-night dive. Nobody can figure out what's going on.

And then the would-be helpers get access to his room. There, covering one entire wall, is a gigantic diagram, made out of photographs, old receipts, newspaper clippings, and statistical tables, all inter-connected with about 157 overlapping lengths of different-colored twine, linking things up.

Reading these threads feels like stumbling into that room.

Exactly. The logic is from some different universe.

To be fair, the brilliant person acting strange was Chief Justice Roberts. These arguments are merely an attempt to make sense of the diagrams and string that Roberts put on the wall.

What Professor Blackman is missing is the possibility of a new savings construction not precluded by NFIB: The law gives people the choice of carrying insurance or having no legal consequence for not doing so. This construction is constitutional because hortatory suggestions don't require authority from an enumerated power.

In support of this construction is the fact that for some people (e.g, those with income below the filing threshold), the penalty for not having insurance was always $0. Presumably, many of these people would choose to not carry insurance.

At the time of the passage of the ACA, the CBO estimated that four million people would choose not to carry insurance and pay the penalty. Blackman noted that in Part III.C of the opinion, the Court said this fact [Blackman's emphasis] "suggests that Congress did not think it was creating four million outlaws."

Blackman dismisses this line as a mere suggestion that does not apply if Roberts' savings construction is discarded.

However, the problem with Blackman's dismissal is it does not apply to the subset of people who chose to not carry insurance and had to pay $0 from the outset. I find it highly unlikely that Congress intended to make outlaws of these people.

I think at helicopter level this is right.

If this gets to SCOTUS, Roberts will have another rabbit handy.

I don't think it takes pulling a rabbit out of a hat to observe it makes no sense for Congress to not make outlaws of people who make a non-zero payment for choosing not carry health insurance while at the same time making outlaws of people who don't owe any payment for not carry health insurance.

"In support of this construction is the fact that for some people (e.g, those with income below the filing threshold), the penalty for not having insurance was always $0. Presumably, many of these people would choose to not carry insurance."

But wait. For people below the filing threshold, the penalty for not filing an income tax return is... nothing. Therefore income taxes are unconstitutional! Cue cheering...

I think this fails to take into account all the implications of NFIB, the experience under the ACA, and the congressional reaction in zeroing out the tax penalty.

It is mostly common ground that Congress did have authority to pass guaranteed issue (GI) and community rating (CR). Congress predicted at the time that an individual mandate (IM) of some sort would become necessary to prevent CR and GI from bollixing up the health insurance markets.

NFIB ruled that Congress lacked the authority (tax power aside, anyway) to enact an IM. But the States have such authority to enact an IM either as a pure mandate or as a tax. (IIRC, the NFIB plaintiffs did make arguments in the district court that would have precluded both the state and federal governments from enacting a non-tax IM, but the district court rejected those arguments, and they were not before the Supreme Court.)

This left the States to decide on a state-by-state basis whether to enact an IM. This had two practical benefits over the original federal IM. First, regulation of pricing in the health insurance markets is a matter mostly of state regulation, so any IM could be crafted to meet the specific conditions in a given state. Second, state IMs could be enacted based on actual experience of how GI and CR affected markets rather than mere prediction.

To have imposed on top of any IM's individual States thought necessary a federal penalty could be viewed as either providing a desirable baseline uniformity or an unfortunate constraint on tailored responses to state-specific conditions. Congress could rationally, in light of NFIB, have taken the latter view, and repealed the penalty to clear the way for the States to enact or not enact IMs as turns out to be necessary to cope with GI and CR.

This is not how I would have gone as an original matter. The construction of the N&P clause in NFIB either (depending on one's spin) leaves Congress unable to exercise its own powers (such as enacting CR and GI) unless it can beg the States to enact necessary complements or lets Congress use its own powers (enacting CR and GI, e.g.) to coerce States into actions (IM mandates) they would prefer to avoid. But that's where we are, I guess.

The construction of the N&P clause in NFIB either (depending on one’s spin) leaves Congress unable to exercise its own powers (such as enacting CR and GI) unless it can beg the States to enact necessary complements or lets Congress use its own powers (enacting CR and GI, e.g.) to coerce States into actions (IM mandates) they would prefer to avoid.

Congress can, as you say, enact CR and GI. In what sense is Congress then "unable to exercise its own powers ?" I think what you mean is simply that if Congress does exercise its own powers the effect will not be what Congress hoped for, unless the States choose to do things that are without Congress's powers.

But this is perfectly normal. Congress can pass a Bill providing for federal funds to support State police in their efforts to identify and scoop up illegal immigrants. But nothing will actually happen unless State governments choose to deploy the state police for that task and draw on the appropriated funds.

I do not believe it is perfectly normal for Congress to be able pass a federal regulation that it is authorized by an enumerated power but then be unable to make the regulation effective by enacting subsequent regulations.

Yes.

One could almost say the Constitution authorizes Congress to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing [enumerated] Powers.

I understand your contempt for Blackman and his arguments, but you do keep missing the point. However black Blackman's heart may be, the substance of his argument is that a number of the points argued by the Texas plaintiffs, which critics such as yourself think are batshit crazy have already beed decided in the Texas plaintiffs favor by SCOTUS in NFIB.

One of them is that the mandate is OK under the N&P clause, which is dealt with expressly and at length by Roberts.

It's explained at some length in Roberts' NFIB judgement. The "subsequent" regulations themselves have to be constitutional and within the enumerated power.

You can't enact a ban on the interstate sale of horse manure, and enforce it with a "necessary and proper" regulation imposing prison sentences on lawyers who agree to defend those accused of interstate traffic in horse manure, on the basis that such jail terms are needed to make the clamp down on the horse manure trade effective.

This is not because there's any doubt that such a subsidiary "effecting" regulation would be fit for purpose, indeed it might be that it's a vital cog in the enforcement mechanism, and without it, horse manure might ooze over state borders entirely unchecked.

Prison sentences against lawyers violate the Sixth Amendment. I'm not seeing anything comparable to invalidate the mandate.

Instead, the mandate was found to not be "Proper" for some other reason. The problem is as Justice Ginsburg put it, "If long on rhetoric, The Chief Justice’s argument is short on substance."

It is NOT a tax, zero or otherwise. That is what Emperor Hussein said.

The congress debated a severance clause and specifically rejected it.

Ergo, ipso facto, henceforth thereunto, the whole mess is and has always been unconstitutional.

But who cares? When a Supreme Court Justice can state publicly that she will never accept a ruling that was handed down by the court, and there is not a peep from any politician, what even matters anymore.

There should be an impeachment, but not Trump.

"When a Supreme Court Justice can state publicly that she will never accept a ruling that was handed down by the court."

Clarence Thomas doesn't "accept" the legitimacy of a wide swath of the last century's jurisprudence. But I doubt you think he should be impeached because of that.

"The congress debated a severance clause and specifically rejected it" - but the 2017 Congress debated killing the whole ACA or just the shared responsibility payment, and did the latter. If the 2017 Congress had considered the mandate essential to the law, why would they have made the mandate non-enforceable?

Arguing about whether or not this is "really" a mandate doesn't accomplish much. If it's unconstitutional, it's not a mandate, it's a nullity. And since no party is arguing that anything bad will happen if you if you don't buy insurance, anybody who thinks the mandate is unconstitutional is free to ignore it and not buy insurance.

There is no need for a judicial remedy, and hence, no justiciable case or controversy.

The people who have standing are folks whose insurance plans are burdened with policies like guaranteed issue, who are inured since congress intended to mitigate the guaranteed issue costs by commanding people to purchase insurance, but can't.

Congress intended to but didn't won't get you into court.

Congress attempted to, but can't.

Regardless of the reason, I don't think Congressional inaction creates injury.

There is still an essential philosophy of law question. Is "mandate" a mandate if there is no penalty/consequence for not doing it. There are other areas of law where we readily say it doesn't matter what Congress calls it (the form part) what matters is how it operates (the substance part). Take Apprendi as an example. Congress can call it a sentencing factor (form) but if it raises the possible punishment it is actually an element of the offense (substance).

Your argument is one of form over substance. It isn't at all clear to me that that is how law should be read, or more importantly here that a "mandate" is actually a mandate when there is no substance behind it.

"There is still an essential philosophy of law question. Is “mandate” a mandate if there is no penalty/consequence for not doing it..."

Sure. Just like a fee is different from a fine.

That is not close to the same thing. Your example you have to pay one way or the other. In this "mandate" question, there is an issue of whether saying you have to do something when there is zero consequence for doing that something actually means you have to do it.

I don't know how you think your example is the same.

Of course they're the same. If I pay a $20 fine, or a $20 fee, the consequences are the same, I'm out $20. But when I pay the fine, I understand that I'm not supposed to do the thing. In this case, the only difference is that the consequences are 0.

There's a difference between a fine and a fee. And there's a difference between a fine of more than $0 and a fine of $0. Just like there's a difference between a fee of $0 and a fee of $0. "the only difference" in this case is dispositive, since the only basis for the unconstitutionality of the mandate in the first place was the >$0 fine (or fee, or chicken, or whatever you wish to call it).

Is “mandate” a mandate if there is no penalty/consequence for not doing it.

Of course not. A panhandler asks you for money. A robber demands it under threat of violence.

There's a difference. That Blackman can't see it, or refuses to because it advances his career was a right-wing legal BS artist doesn't change the facts.

You’re half right, but you miss Blackman’s point - there is a difference, Congress did the wrong one for what you want (who knows what “Congress” wants), and the only thing that matters is the consequence of Congress being incompetent at its job.

The real question of course is: since Congress effectively severed the mandate by making it toothless, isn’t that evidence that they intended it to be severable? So sever it. No more mandate to do something “or else.”

Is Blackman's point not the simpler one that whatever view you take of these matters de novo, they've already been decided by SCOTUS in NFIB.

It is because he thinks that since they didn't talk about the penalty when discussing the mandate it is wholly irrelevant to their conclusion. That seems like nonsense to me. There was no question it was a mandate in NFIB because it was backed up by the penalty. That is/was not in dispute, so not mentioning it is hardly proof of anything.

Judges instruct jurors that they may not convict the defendant unless they are convinced of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Is it the position of anybody here that this is not a mandate, because jurors have no consequences for ignoring it?

The hypo dodges the issue. It is my position that jury instructions are not regulations of economic inactivity, and in light of that don't present a CC issue at all. (Of course, courts' authority to issue instructions is not premised on the CC in the first place. And even penalty-attached jury instructions aren't affecting economic inactivity.)

You cannot have a CC problem unless the government can coerce you to purchase something. And here, the government cannot coerce you to purchase something. That's true whether we refer to it as a "mandate" a "command" a "suggestion" a "fee" a "fine" a "tax" or a "chicken". It makes no difference. What matters is the substance of the thing. And not because of philosophy, but because courts are required to look to look to the substance of the thing for constitutional-conflict avoidance purposes.

I feel really sorry for the constitutional law students of a professor who teaches them that the portion of a Supreme Court opinion joined by a majority of the justices, supporting the ultimate holding of the Court, is not in fact the "controlling" opinion; rather, the "controlling opinion" is actually some dicta that one justice wrote for himself.

Hopefully those kids will have other professors set them straight. Though, given that they can barely breach a 154 on the LSAT, I suspect they're just a lost cause.

I have no idea why the VCers wanted to give this guy a spot on their roster, but an ambitious moron is still a moron.

The word moron is inapt. One must have a great deal of magnetism (lacking here) or intelligence in order to convince large groups of people that they and their children are better off with the freedom to die early than with access to health care.

"Section 5000A(a) could be read as offering a "choice" to taxpayers from 2012 through 2017... But Section 5000A(a) can no longer be read that way." -- but it's less coercive now than before. How can less coercion mean less choice? Now you can add $0 to your taxes and feel compliant, just as before your could add $700 to your taxes and feel compliant.

"Where are the statements from those who voted in 2010" -- then, where are the statements from those who voted in 2017 saying we meant to repeal the whole ACA?

Roberts screwed the pooch in his decision by making it contradictory:

"The most straightforward reading of the individual mandate is that it commands individuals to purchase insurance. But, for the reasons explained, the Commerce Clause does not give Congress that power. It is therefore necessary to turn to the Government’s alternative argument: that the mandate may be upheld as within Congress’s power to “lay and collect Taxes.”

Roberts should have merely struck the mandate, and if he just had to save the statute he should have made it clear there was no mandate, only a tax on not buying health insurance. But by upholding the mandate as a tax he set us up for round 2.

But that's the sort of garbage you can end up with with one person straddling the middle and 4 votes on either side picking and choosing which parts they like enough to make it the law of the land.

This argument kinda gives away the game, then - even if Roberts is wrong, that doesn't create a right to a second bite at the apple. Which is what Blackman is flowcharting so hard for.

But that’s the sort of garbage you can end up with with one person straddling the middle and 4 votes on either side picking and choosing which parts they like enough to make it the law of the land.

That is not what happened on NFIB. The four conservatives besides Roberts did not join any part of the Court's opinion, and instead wrote in dissent. The fact that they might have agreed with Roberts' opinion that the mandate exceeded Congress's powers does not make it the "law of the land."

This is what Josh and Randy's "analysis" consistently, and doggedly, obfuscates, to the detriment of their readers (and, apparently, their students).

Have we ever before had a case where a necessary predicate to the holding was agreed to by five or more justices, but less than five of those justices joined the controlling opinion establishing the necessary predicate?

[…] first post considered standing. My second post focused on the constitutionality of the individual mandate. This final post will analyze […]

[…] first post considered standing. My second post focused on the constitutionality of the individual mandate. This final post will analyze […]

[…] first post considered standing. My second post focused on the constitutionality of the individual mandate. This final post will analyze […]

If SCOTUS in 2012 had thought the mandate is inseverable, it would have struck down the whole ACA when it read the mandate out of the law.

"Zeroing out the penalty in no way affected the mandate, which was a separate statutory provision" -- so the 2010 ACA had two separate provisions, a mandate and a tax; SCOTUS struck the mandate and kept the tax, _and_ didn't strike the rest of ACA. So, SCOTUS clearly thought in 2012 that the mandate is severable . Why would that change? If "Zeroing out the penalty in no way affected the mandate", why would it have affected the _severability_ of the mandate?

[…] I think NFIB rejected that reading. I won’t rehash that argument here. But let’s assume I am right for a moment. If […]

[…] I think this citation was in error, and fails to account for the structure of Lukumi. Like with NFIB v. Sebelius, Supreme Court decisions must be read from top to bottom. It is risky to quote language from later […]

[…] I think this citation was in error, and fails to account for the structure of Lukumi. Like with NFIB v. Sebelius, Supreme Court decisions must be read from top to bottom. It is risky to quote language from later […]

[…] I think this citation was in error, and fails to account for the structure of Lukumi. Like with NFIB v. Sebelius, Supreme Court decisions must be read from top to bottom. It is risky to quote language from later […]

[…] I think this citation was in error, and fails to account for the structure of Lukumi. Like with NFIB v. Sebelius, Supreme Court decisions must be read from top to bottom. It is risky to quote language from later […]