The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Court orders online tabloid not to post 'any articles about' former Obama nominee to the federal CFTC

1. Chris Brummer: Chris Brummer is an expert in banking and finance law at Georgetown University Law Center, and to my knowledge a highly regarded scholar. Indeed, in March 2016, Brummer was also nominated by President Barack Obama to serve on the Commodity Futures Trading Commission; his nomination was withdrawn in March of this year. And even before the nomination, Brummer held a prominent position, as an adjudicator on the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) National Adjudicatory Council (NAC). In his words,

As a not-for-profit organization empowered by Congress to regulate broker-dealers and exchanges, FINRA brings disciplinary actions against those believed to have violated key rules, like committing fraud or market abuse. The NAC is FINRA's appellate body for reviewing any disciplinary decisions members would like to contest. … As a member of the NAC, I am one of 14 individuals who rotate on occasion to hear varying cases on appeal.

The NAC is a private body, but it plays an important role in a government-authorized self-regulatory system, and indeed its decisions are subject to appeal to a government body, the Securities and Exchange Commission. Whether or not that role makes Brummer a "public figure" for the purposes of determining when libel law damages are available to him, Brummer's actions as an NAC adjudicator were certainly matters of public concern. And his nomination by the president certainly made him tantamount to a public figure or a public official during the time the nomination was pending.

2. The Blot: In December 2014, Brummer participated in an NAC decision that upheld a permanent ban on two stockbrokers, Talman Harris and William Scholander, from associating with any FINRA-regulated firm. The stockbrokers are both black, and so is Brummer (you'll shortly see how that has affected events). Harris has since been convicted of fraud in a different matter and Scholander has pled guilty to fraud in an aspect of that matter.

As a result, Brummer drew the attention of The Blot, which I think can be fairly described as an online tabloid that's big on insults and leaps of inference (at the very least). The Blot is run by Benjamin Wey, a rich financier who is now under indictment for securities fraud, though some important evidence against him was recently thrown out on Fourth Amendment grounds. [UPDATE 8/10/17: The government has now dropped the charges against Wey.] Wey also recently lost a high-profile sexual harassment and defamation lawsuit, Bouveng v. Wey, which also involved statements posted on The Blot.

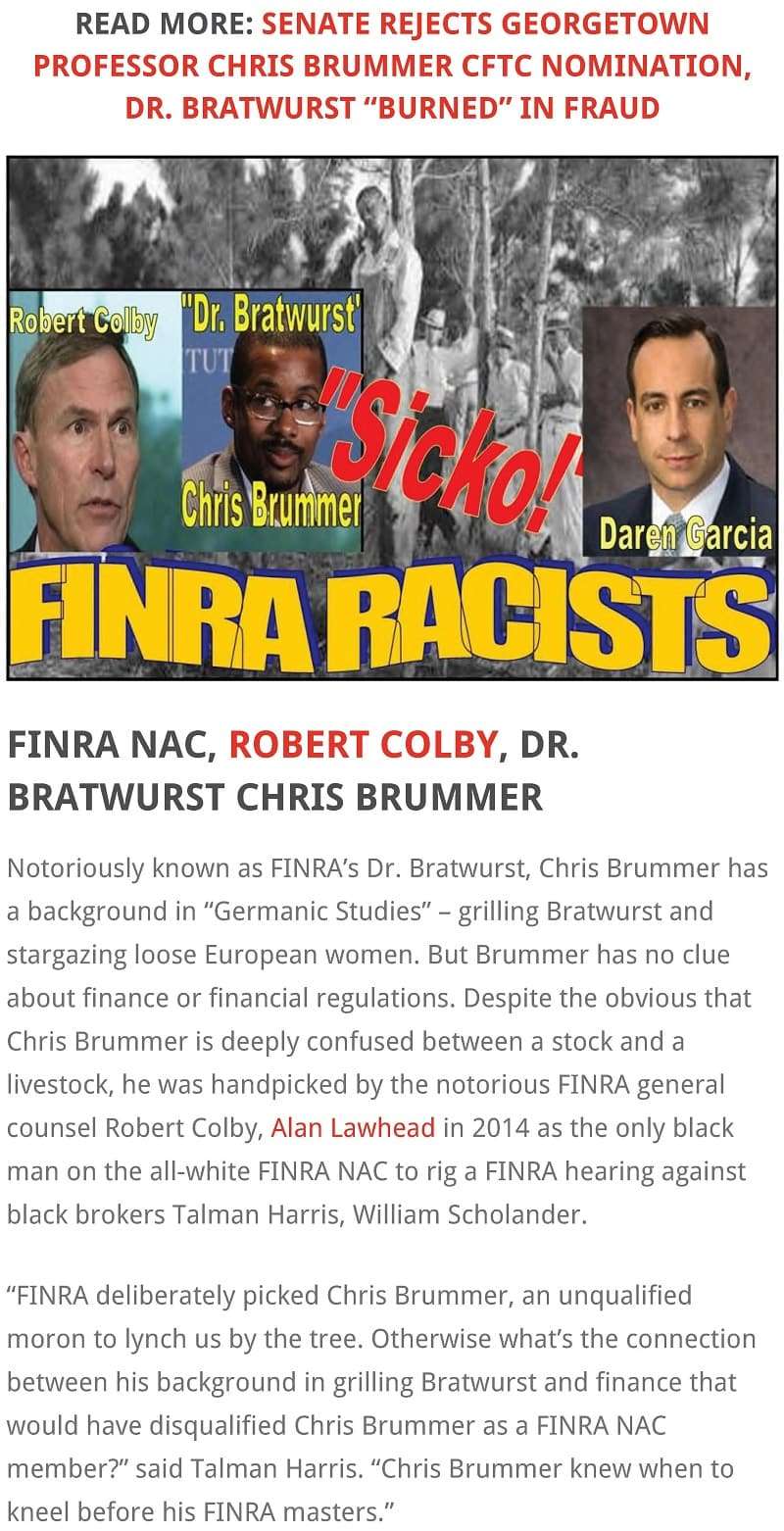

The Blot began to run articles such as this (I should stress that I have no reason to believe the truth of any of the accusations in the article; I'm passing this along just so you could see some of the material that forms the basis of the lawsuit):

Other posts likewise, in the words of the trial court decision, "continuously refer to [Brummer] as a 'phony law firm dropout, imbecile, being caught up in fraud, an Uncle Tom,' and asserts that Plaintiff had sexual affairs and engaged in lewd conduct including being a 'suspect in a rape case.'"

Some of the articles were posted before Brummer was nominated to the CFTC; others (such as this one) were posted after that. Brummer's lawyers suggest the statements were posted by Wey himself (under a pseudonym) or at Wey's behest, and suspect that they stem from Wey's having been in business in the past with Harris and Scholander.

3. The lawsuit: Unsurprisingly, Brummer sued Wey and Wey's companies for defamation, as he had every right to do. (The lawsuit was filed in April 2015, before Brummer's CFTC nomination, but the allegations have been updated in light of later posts.)

The normal course of such a lawsuit would be for there to be a trial, in which the fact-finder would determine whether particular factual statements about Brummer were false (and were said with the requisite mental state, but we'll set aside here), defamatory, and made by Wey or Wey's agents. If they were, then Brummer would get compensatory damages and possibly presumed or punitive damages (if the statements were said knowing they were false or likely false). And in many states, Brummer would be able to get an injunction requiring that Wey remove the particular statements found to be false and defamatory, and barring their repetition. See, e.g., Balboa Island Inn, Inc. v. Lemen (Cal. 2007); Hill v. Petrotech Resources Corp. (Ky. 2010).

4. The Injunction: But this lawsuit didn't play out this way. Instead, the judge issued a preliminary injunction that banned defendants "from posting any articles about the Plaintiff to The Blot for the duration of this action," and that they "remove from TheBlot all the articles they have posted about or concerning Plaintiff." The injunction by its terms lasts until trial, which could be many months away, and the plaintiffs asked that the injunction be made permanent after that trial.

This is not at all limited to false and defamatory factual accusations; it covers even constitutionally protected true statements, or constitutionally protected opinions. Under the injunction, The Blot can't post anything faulting Brummer for seeking and getting this injunction. It can't post anything saying that Brummer's nomination was rightly withdrawn. If Brummer is renominated, it can't post anything criticizing the nomination. It can't post accurate statements about what Brummer did (e.g., that he participated in handing down the Harris/Scholander decision), or opinions about Brummer (e.g., that he is an "Uncle Tom" for participating in that decision).

What's more, the injunction comes before any trial on whether the statements are false; it is issued based on a likelihood of success on the merits, not based on any conclusion that Brummer should win on the merits. The injunction makes no specific findings that any specific allegations are false; it labels the items on The Blot as "offensive articles," and says that they are "capable of injuring [plaintiff's] standing and reputation," but that would not be enough for a libel judgment even if such findings were entered after a full trial.

Preliminary injunctions in libel cases entered before any trial on the merits are generally treated as unconstitutional "prior restraints." To quote the Kentucky Supreme Court's decision in Hill, "an injunction against false, defamatory speech" is allowed "only upon a final judicial determination that the speech is false. … Until such determination of falsity, however, [the Kentucky Constitution's analog to the Free Speech Clause] is best interpreted as proscribing a preliminary restraint upon the alleged defamatory speech. … Neither a restraining order … nor a temporary injunction … may be used to enjoin allegedly defamatory speech." Likewise, as the California Supreme Court held in Balboa Island Village Inn (quoting a concurrence in an earlier case), "A preliminary injunction poses a danger that permanent injunctive relief does not; that potentially protected speech will be enjoined prior to an adjudication on the merits of the speaker's or publisher's First Amendment claims."

Some New York intermediate appellate cases do seem to authorize preliminary injunctions against libel, though the dominant view throughout the country - and, I think, the correct view - is that any such preliminary injunctions are not allowed. But whatever one thinks about the preliminary/permanent injunction distinction, either kind of injunction against all speech by defendants about Brummer is clearly unconstitutional.

Indeed, in many ways this case is a reprise of the injunction in Near v. Minnesota (1931), the very first case in which the Supreme Court struck down government action on freedom-of-the-press grounds. Near was the publisher of a scandal sheet (the Saturday Press) that repeatedly attacked several government officials, often using anti-Semitic allegations. The trial court concluded that various editions of the newspaper were "chiefly devoted to malicious, scandalous and defamatory articles," and therefore permanently enjoined the defendants from producing "any publication whatsoever which is a malicious, scandalous or defamatory newspaper" and in particular from publishing the Saturday Press.

In Brummer, as in Near, the judge apparently concluded that the defendants had engaged in repeated libels in the past, and tried to prevent their recurrence by banning a wide range of speech (rather than just banning future libelous factual claims). Yet the Supreme Court in Near rejected the injunction. Though specific libelous statements could lead to civil liability and even to criminal punishment (criminal libel prosecutions were more common back then than they are today), an injunction against a wide range of future statements could not be constitutional.

I should note that the Near injunction covered all "malicious" or "scandalous" publications about anyone, while the Brummer injunctions all publications about Brummer in particular. But if a court may ban speech about one target of a newspaper (as the judge did in Brummer), then the judge could equally ban speech about all of the newspaper's targets, so long as each of the targets sues. And though the Near injunction was permanent and the Brummer injunction was just pending trial, suppressing speech even for months remains unconstitutional, as later cases have made clear (e.g., Vance v. Universal Amusement Co. (1980)).

Indeed, in the decades since then, the court has continued to stress that any injunctions against speech with a particular content must be limited to speech that is actually constitutionally unprotected (such as obscenity, or commercial advertising proposing illegal transactions, or perhaps libel). They cannot prophylactically aim at a wide range of speech, simply because some instances of that speech are unprotected.

5. The "Incitement"/Threat Theory: Though the court order seemed to primarily focus on the material being defamatory or "offensive," Brummer's motion in support of the order also alleged that the material was threatening and inciting of violence:

For two years, Defendants have been publishing objectively false and reprehensible stories designed to stimulate outrage against Professor Brummer. Defendants recently added photographs of lynching victims beside pictures of Professor Brummer, his counsel and at least one regulator, along with a "comment" suggesting that Professor Brummer should be shot.

The lynching and gunfire espoused by Defendants are the last pieces of the proverbial puzzle. Infused with these overtures to deadly violence, the entire content of the Defendants' websites relating to Professor Brummer constitutes a classic and serious threat of physical harm. The Court has full authority to enjoin these threats of physical harm and inducements to violence. Pending the entry of final judgment, the Court should exercise that authority to protect Professor Brummer and others from the menacing activity and personal risk to which Defendants are unlawfully subjecting them. Specifically, the Court should order immediate removal from the websites of Defendants of the lynching photographs and all "stories" about Professor Brummer ….

But I don't think that's right. First, the lynching pictures were pretty clearly claims that Brummer was figuratively the lyncher, not threats to lynch Brummer. The picture labels Brummer and the others as "FINRA RACISTS," and is accompanied (at the start of the second paragraphs below it) by a supposed quote from Harris saying, "FINRA deliberately picked Chris Brummer, an unqualified moron to lynch us by the tree."

Brummer's reply points to "the deadly significance of the lynching imagery to him as an African-American who grew up in the deep South," and cites Brummer's affidavit that states, "As an African-American from the deep South, I recognize that the lynching victims portrayed in the images could well be my own ancestors, and that these escalating attacks are meant to incite others and terrorize me." But an accusation, however hyperbolic, that someone is guilty of lynching isn't itself tantamount to a threat to lynch (just as accusing me of being a Nazi, for instance, for being complicit as an Israel-supporting Jew in supposed crimes against Palestinians, wouldn't itself be a constitutionally unprotected threat of violence - despite the atrocities that Nazis had committed against Jews - and couldn't be suppressed by a court).

As to the shooting comment, it read "These FINRA motherfuckers ruin lives! Fuck them or shoot them? Both perhaps." But its author, "Bill," remains unidentified; plaintiffs suggest that defendants posted that comment themselves, but there seems to be no solid evidence of that. And in any case, even if the comment were viewed as a constitutionally unprotected true threat of violence, this comment cannot justify an injunction "order[ing] immediate removal from the websites of Defendants of the lynching photographs and all 'stories' about Professor Brummer,"

Brummer's incitement theory is also legally unsound. To be punishable incitement, speech must be intended to and likely to produce imminent criminal conduct - i.e., conduct within the coming hours or maybe days, rather than conduct at an unspecified future time. See Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969); Hess v. Indiana (1973). The motion doesn't even cite Brandenburg, Hess, or any other incitement cases, or explain why this extremely demanding standard for punishable incitement is satisfied.

6. The Attempt to Persuade Google to Remove "Racial Hate Speech": Even before the injunction was issued (the day before, as it happens), Brummer's lawyers asked Google to deindex material about Brummer - in large part on the grounds that the material included "racial hate speech and slurs."

To the best of my knowledge, Google has not acted on this request, and is not about to start suppressing criticism simply because it contains alleged "hate speech," "lynching iconography," or "racial slurs." Google is free to deindex materials as it likes, and people are free to ask Google to do so; but the perils of Google getting into the business of deciding which criticisms - again, of prominent decision-makers who had even recently been presidential nominees to high office - seem quite clear, and seem to be very good reasons for Google to stay out of this business. This is the first time that I've seen a prominent plaintiff and a prominent law firm even ask Google to deindex material partly on the grounds that it consists of "racial hate speech and slurs."

7. The Current State of the Litigation: Wey's lawyers are appealing the injunction, and have indeed gotten a temporary stay "pending an expedited hearing on the motion [for a stay] by a full bench of this Court." The basis for the stay is that it is not clear that Wey was indeed the author of the allegedly defamatory posts:

Shiamili v Real Estate of Group of New York (17 NY3d 281 [2011]) and the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S.C. § 230(c)) bar restraints against interactive computer service providers (that is, entities that merely provide an internet platform for material posted by third-party users), as opposed to information content providers (that is, entities that actually generate and post statements on the internet). In a federal court matter in 2015, defendant Benjamin Wey gave sworn testimony stating that he was, in fact, the author of the posts appearing on TheBlot.com. This matter, however, presents issues of fact regarding whether any defendant, including Wey, is still acting as an information content provider, as opposed to acting as an interactive computer service provider.

And I hope that the appellate court will ultimately vacate the injunction for good, preferably by making clear that such an injunction violates the First Amendment and not just on § 230 grounds.

* * *

As readers may gather, I don't find the posts on The Blot to be at all credible. I sympathize with Brummer's anger at seeing them there. I think he may have an eminently sound libel damages claim, and maybe even the basis for a permanent injunctions ordering the removal of posts that had been found to be libelous.

But here we have someone whom a president had recently nominated for a high federal government position - someone who is still being discussed as a possible future nominee - someone who even independently of that appointment has wielded considerable power within a self-regulated industry, over people's livelihoods and over investor complaints. And we have a court ordering a publisher (however lacking in credibility the publisher might be) to just stop saying anything at all about this person: anything false, anything true, any expression of opinion, anything whatsoever. That is remarkable, and in my view unjustifiable.

UPDATE: The post originally made it sound like the convictions were related to the FINRA matter; they were not, but related to other frauds that Harris and Scholander had been involved in, and I've clarified this accordingly.

Show Comments (0)