The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The Disneyfication of Star Wars

Last week, Io9 ran a quite insightful story by Katharine Trendacosta about Disney's baleful influence on the Star Wars universe, titled "Star Wars Is All the Same Nowadays, and It's Becoming a Problem." Noting some worrisome changes in the direction of the new Han Solo movie, Trendacosta writes:

We're learning a lot more about what Lucasfillm feels is acceptable within its universe and what isn't. The problem is that what's acceptable looks to be very, very narrow.

…

These anthology films seemed like they would be ideal places to experiment with Star Wars and keep it from getting stale. One of the things that so ignited the imagination of fans was the world-building of Star Wars, which created a universe that could support all sorts of stories. Tragedies, comedies. Stories about saving the universe and more personal, private ones. The fact that all of those things easily fit in the universe makes it feel real.

The anthology films should have been a place to take advantage of that. But instead of the full rainbow, we're just getting many shades of green.

And here's more:

The overall quality of the Star Wars universe is better now. Every installment-movie, book, TV show, comic, game-is, at worst, at the low end of mediocre. The old universe's canon had some truly low lows that are gone now. But it also means that the highs aren't as high, and the result is the Star Wars universe isn't as much fun. Even the worst old [Expanded Universe] book felt like it was trying to do something new.

Star Wars feels smaller than it used to, which is a shame when there is literally an entire galaxy to explore. Maybe if Lucasfilm would give its directors, authors, and artists just a bit more leeway, it could see that Star Wars doesn't have to always revolve around the original trilogy. There's literally an entire galaxy to explore, and I for one would like to see it.

I've been worried about this for a while.

These observations are unfortunately consistent with an essay I wrote last summer (during my sabbatical from this blog) about the death of the Star Wars universe. From my essay (actually a review of Cass Sunstein's fun book, "The World According to Star Wars"):

It all went wrong with The Force Awakens. (Sunstein says: "It doesn't have anything like Lucas' originality, but it's still awfully good." (154))

Science fiction and fantasy - Star Wars is both - make their mark by the worlds that they create. That world is part of what made the original Star Wars trilogy great. Watching it for the first time, you felt like you were joining the middle of the story - a story with a rich, fascinating past that you had to both take for granted and slowly discover. But more than that, you were joining a universe. The universe had lightsabers, force-wielding Jedi, elaborate starships and dozens and dozens of planets and alien species each of which (it was implied) had their own rich lives somewhere beyond the movies' plot. Sunstein tells us that Star Wars "contains a whole world." (xii) "A whole world" undersells it - Star Wars contained many, many worlds.

This is why The Force Awakens was a disappointment. What the franchise most needed was a plot that captured the vastness of the Star Wars universe - a plot that included things we had never seen before, and nobody named "Skywalker." Instead, we saw Darth Vader's family drama continued for yet another generation, and scenes and locations that were lifted right out of the original trilogy. (Even Rey, one of the most heralded new characters in the movie, is likely related to either Obi-Wan Kenobi or Luke Skywalker.) No moment in the The Force Awakens even approached the thrill of first seeing a lightsaber ignite.

What is more, the new movie physically compressed the Star Wars universe. In the original trilogy, we're repeatedly reminded of the scale of the galaxy. Some planets are the "bright center to the universe" and others are "the planet that it's farthest from." It takes notable screen time for the characters to get from place to place. This contributes to the feeling of a real galaxy, with worlds full of possibility. By contrast, in The Force Awakens travel time is ignored, and even the newest world-destroying superweapon no longer needs to travel anywhere to destroy its targets.

The flatness of the new Star Wars universe is confirmed by the emotional emptiness of the movie's climax. The good guys, the Resistance, fail to destroy the superweapon before it wipes out multiple planets that house, near as we can tell, much of the Republic's population. This is a cataclysmic disaster. But in the movie, it passes as an afterthought. By this point the audience has stopped taking seriously the humanity of those off-screen worlds.

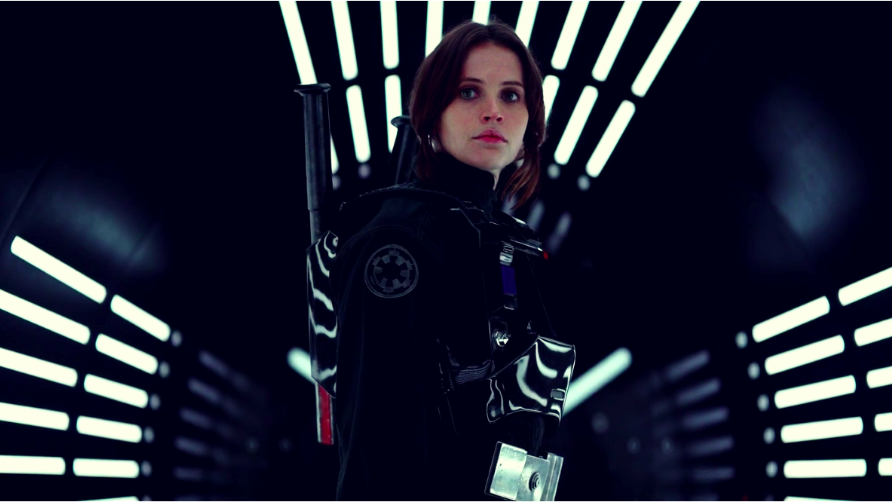

Now, unlike Trendacosta, I took a much more favorable view of the more recent, off-saga, "Rogue One." That movie was surprisingly good on each of the points I just mentioned above: We got new characters, new mysterious force traditions, and a sense of moral ambiguity that was almost shocking by comparison with the vanilla vs. chocolate of "The Force Awakens." So I hoped that we were going to get more off-saga and interesting movies like that in the future. I now worry that even that won't happen.

(Unlike Trendacosta, I also took a much more favorable view of the Expanded Universe, though I will leave that debate for the truest Star Wars nerds who want to read the whole essay. And for those truest nerds, if you haven't read the Mallory/Ma'allory discussion at the Toast, you must read that too.)

Now in one sense, it is too soon to tell what the future of Star Wars looks like. We have a new movie this year, another new movie next year, etc. But in another sense, it may be too late. Diehard Star Wars fans have had to wrestle with betrayal for decades. From the end of my piece:

But maybe there is hope - hope that comes from a minor but ominous episode in 1997. In that year, George Lucas released a "special edition" of the original Star Wars trilogy, with several new scenes and alterations, mostly mediocre but mostly harmless.

There was one very harmful change, however, to one of the first scenes starring Harrison Ford's Han Solo, who is threatened by a Rodian bounty hunter named Greedo. After a bit of tough talk, Han covertly shoots Greedo under the table, then tosses the bartender some money with the quip, "sorry about the mess." The scene establishes Han's character - the quick-shooting scoundrel.

But in the revision, Lucas had Greedo shoot first, and inexplicably miss despite shooting at point-blank range. This converts Han from crafty to lucky, and allows us to think that he's the kind of a guy who would hesitate to launch a preemptive strike. The revision was so obviously wrong about the real Han Solo that it sparked the rallying cry, "Han Shot First!"-a reminder that there was a truth about the Star Wars universe even when the author tried to take it away from us.

That episode taught true Star Wars fans about the dark side of George Lucas. But it also taught us we could rally around a fictional universe, even when betrayed by its author. Fans could insist that the scoundrel version of Han Solo was really canon, even if the author himself disagreed.

So maybe the real lesson comes back to Sunstein's "freedom of choice." (193) Each of us can love our own version of the Star Wars universe. Sunstein is free to love the world of the movies that he recounts in his book. Others of us are free to love what we know to be the real Star Wars, unblemished by its creator - a galaxy far, far away, where the Extended Universe lives, space is still vast and trackless, and Han shot first.

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?