The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Crime on the virtual street: Haptics, algics and assault

I'm blogging excerpts this week and next week from Mark Lemley's and my new article, "Law, Virtual Reality, and Augmented Reality." (Click on the link to see the whole article, including footnotes.) This post is from the criminal-law part.

One general assumption we make throughout: Virtual-reality and augmented-reality technology (think something like Google Glass) will get better, cheaper and more effective at rendering lifelike human avatars that track the user's facial expressions. I think that's a safe assumption, given the general trends in computer technology, and one that doesn't require any major technological breakthroughs; but we are indeed prognosticating about technology that's likely at least a couple of years out.

* * *

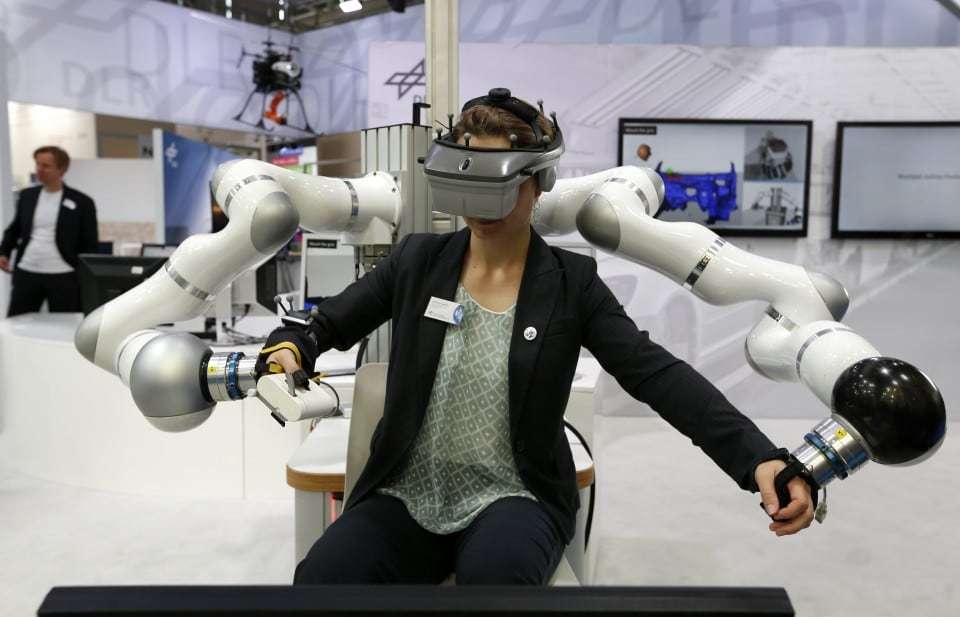

So far, we've talked about harms that can be caused by the audiovisual features of VR - the only features that are well-developed now. But let's turn to features that VR is likely to acquire soon: haptics.

Haptics are to touch what are optics are to sight. Existing two-dimensional games have very simple haptics: a PlayStation DualShock controller that vibrates when you drive over bumps or run into something, for instance. But the immersive nature of VR can offer quite a bit more.

Gloves that reproduce sensation on fingers are haptics. So are temperature controls that can make VR tourism more realistic. So are devices that could cause feelings of physical resistance so that a virtual sword fight would yield realistic sensations when your virtual sword hit your virtual opponent's. And one can also embed haptics and remote control into sex aids - a business called teledildonics.

Teledildonics raises the possibility of haptic sex crimes. Unconsented-to sexual touching is a serious offense and should be so even if the person doing the touching is not in the room with you. True, sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy aren't threats in the virtual world; and some people may be less troubled by unwanted remote fondling through their haptic interfaces than by unwanted in-person fondling. But we think it likely that people will be justifiably upset enough by such unwanted touching that it would merit punishment.

Similar issues come up outside of sex. Say some people enjoy a particular game that's supposed to simulate a dangerous physical activity (fighting, mountain climbing, flying an airplane) but are frustrated that death or injury in the game has no real consequences. They think it makes themselves and other players reckless and distorts the game's realism. Playing poker for matchsticks, it is often said, isn't the same as real poker. Likewise, playing at sword fighting when being speared through the neck just means "Game Over" isn't as realistic, they think, as it should be.

So they think players ought to have skin in the game, as it were: Certain events should trigger something bad - not death (they're not that hardcore) but physical pain. Indeed, paintball players sometimes take the view that the painful sting of being hit enhances the game by making players work harder to avoid being hit, or just by making the game exciting. Likewise, some social psychology experiments punish people who lose a game by requiring them to consume a substance that is extremely unpleasantly bitter, to encourage participants to take the game seriously.

Imagine, then, that a VR setup can have an optional hardware feature: a device that produces an electric shock that is not dangerous but is painful. (One might think of it as "algics" rather than normal haptics.) People who want to play "Extreme Sword Fights" (let's call it) must have the device attached, and when they are hit with the virtual sword, they get a real shock. Here, unlike with our previous examples, we do have actual physical contact with the victim's body, albeit contact triggered at a distance rather than by someone standing next to you.

So long as the shock doesn't pose any serious physical danger, causing the shock by hitting someone in-game wouldn't be battery. Battery generally requires nonconsensual touching, at least so long as it doesn't involve a public fight that risks spreading, or serious physical damage that goes beyond mere pain. This is why a wide variety of often painful activities, from football games to mild sadomasochism, are legal. And you consented to be hit by a virtual sword - or at least to run the risk of being hit. By contrast, triggering the haptics outside the game - for instance, by hacking someone's VR rig to give them a surprise electric shock - presumably would be nonconsensual.

So far, so good. But consent in a virtual world has some nuances that we might not expect, as we see in the next section.

Show Comments (0)