The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Judge Leonard I. Garth, 1921-2016

After law school, I was a law clerk for Judge Leonard I. Garth of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit. Judge Garth died Thursday at the age of 95. I was very fortunate to know him as a boss, mentor and good friend. In this post, I'd like to celebrate his life on the event of his passing.

Judge Garth was in both attitude and demeanor a model judge. He wanted to get every case right, no matter how obscure it was, and he did cases by the book. If you listen to Richard Posner, you'll hear that judges reach decisions that seem sensible on pragmatic grounds and then reason backwards to get there. Not Judge Garth. He was obsessed over the record and the standard of review. He checked and double-checked whether jurisdiction was proper, because if there was no jurisdiction the court had no authority to decide the case.

He also insisted that his clerks give as much attention to hand-written pro se cases as to appeals by lawyers from big firms, on the thinking that every case was equal no matter whether the party was rich or poor. Clarence Earl Gideon wrote his cert petition in pencil, the judge would remind his clerks. You never know which pro se case might be the next Gideon.

Of course, like every judge, Judge Garth would get instincts about which side was right. But he had an impressive ability to put that aside if he came across caselaw or something in the record that pointed in a different direction. He saw room for case-by-case equity. And he was carefully attuned to the human side of the cases he decided. But more than any judge I have met, he saw the role of judges as being to follow the law and play it straight. (An aside: When I was in law school, shortly after accepting the clerkship, Judge Garth came to Harvard to judge the moot court competition. We met for coffee, and on our way to the local Starbucks a panhandler approached us and asked for money. Judge Garth stopped, pulled out his wallet, and gave the man a dollar or two. An interesting signal to send a future clerk.)

I spoke about the experience clerking for Judge Garth in an interview at SCOTUSBlog in 2014. Here's what I said, which you can watch starting at the 13:20 mark, slightly cleaned up to make it more readable:

I applied for clerkships and accepted a position with Judge Leonard Garth on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, who at the age of, I think, 93 now, is still hearing cases. I just spoke with him a few days ago. It was a wonderful experience. After clerking I remember speaking with other law clerks, and one of the issues we talked about is to what extent is the law political. To what extent do judges' political views impact their decisions. And I remember speaking to a law school friend who clerked on another circuit. And his response was that it was all political. The liberal judges voted the liberal way, and the conservative judges voted the conservative way. My experience was just completely different. Judge Garth would go where the cases took him, and that's how he decides cases. It was all on the record. It was very much the way things are supposed to be. That's the sunny version of how law is supposed to work, and it was was how it worked. It was wonderful. He's intensely involved in the cases, and is looking at the cases and is looking at the record and is active at oral argument. It was a great experience.

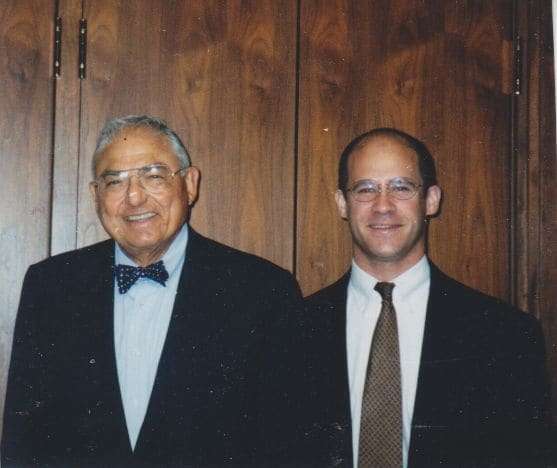

While I'm thinking back to that year, here's picture of the Judge and me at the end of my clerkship in the summer of 1998.

Leonard Garth was also remarkable for his passion about the law throughout his long life. Although he became a senior judge in 1986, he never stopped working. In his late 80s, he and his wife, Sarah, moved from New Jersey to a retirement community in Connecticut to be near his grandchildren. But that didn't mean the judge stopped working. The 3rd Circuit agreed to have an office of the court installed in the Garths' retirement community. It was a little outpost of the 3rd Circuit inside the 2nd Circuit, located in a small apartment across the hall from the Garths.

Into his 90s, Judge Garth would work all day at the retirement community with the help of a law clerk. When I would meet him for lunch - usually around once a year, when I could finagle an invitation to speak at Yale nearby - he would express astonishment that a circuit panel had done this or delight that Judge So-and-so had done that. It was amazing. Here he was in his 90s, getting around his retirement community in a scooter because walking was difficult, and his passion for the work of the 3rd Circuit was undiminished.

Even in the last year of his life, after he had given up serving on merits panels and his court office was closed, he helped the court by reviewing en banc petitions from his iPad in his apartment. As his close friend and colleague the late Judge Edward Becker once said of him, Leonard Garth was "all judge." (If you're interested in watching him discuss the role of the federal judiciary, here's a C-SPAN panel from 1986 that gives you a flavor.)

At this point you're probably wondering: Judge Garth sounds great, but why haven't I heard much about him before? He served as a federal judge for 47 years, but he wasn't particularly well known. He may be best known as "the judge that Justice Alito clerked for," rather than for his own work. I think the reason is that he wasn't an unusually gifted writer. When we talk about "great judges," we usually mean "judges who are great writers." Writing skill has an outsize role in how we assess judges because it is easy to recognize. Anyone who reads an opinion can grade the writing, while few readers know the relevant caselaw and almost no one knows the record. Judge Garth's writing was more adequate and workmanlike than sharp and memorable. His focus was making sure the court's reasoning was clear to the parties litigating the case rather than trying to attract or entertain outside readers. I suspect that's why he wasn't better known.

I've spoken about Garth as a judge, so let me talk about him as a person. I'm obviously biased, as we were close. But Judge Garth was simply one of the most delightful people I have been fortunate to know. On one hand, he carried a courtly demeanor. Clothes don't make the man, but he was a gentleman of the World War II generation that saw bow ties as a common alternative to neckties and he always wore one to the office. (He was often seen wearing his favorite Blenheim bow tie, the style popularized by Winston Churchill; every Garth clerk received one at the end of the year.) On the other hand, he was marvelously warm and caring. He was concerned with how the janitor was doing. If a former clerk called, he wanted to know how the entire family was doing; what you thought about the latest news; and whether you had heard from any other former clerks. I spoke with him around two months ago, and even by that point it was a joy to connect.

Finally, I couldn't talk about Judge Garth without also celebrating his wife, Sarah. The judge and Mrs. Garth were an adorable pairing, and they were blessed to be together for a remarkably long time. They were married for 72 wonderful years, from 1942 until her passing just last year. Now I loved Judge Garth, but I loved Mrs. Garth. She was just lovely; opinionated and strong while also a social hub for her many friends. All of us are on the earth for only a short time, and how much good time we have is usually just a matter of chance. But there's a certain correctness in the Garths being together and "with it" for a large chunk longer than most of us. I remember the judge once saying that when he was a young man, he and Mrs. Garth had the honor of meeting the president in the Oval Office. My recollection is that when I asked which president they had met, the answer was Roosevelt.

What a life.

Show Comments (0)