There's No Evidence That Climate Change Has Increased the Rat Population

A widely reported study relies on weak data, inaccurate statistics, and misleading references to support its claims.

HD DownloadAs the earth gets warmer, there's one species that supposedly will really benefit."Climate Change is amazing," reported National Geographic. "If you're a rat."

The horrific prospect of these pizza-dragging, toilet-bathing, plague-spreading, baby-eating, cannibalistic beasts swarming the sweltering streets of our major cities helps to explain why a recent study allegedly demonstrating a global warming-induced increase in the urban rat population received such widespread media coverage. As is often the case, journalists were not sufficiently skeptical, nor did they take the time to read the study closely.

Published in Science Advances with 19 co-authors, this paper contains nothing meaningful about either climate change or rats. It relies on weak data and inaccurate statistics, and uses misleading references to support its claims. There is no evidence to suggest that global warming is contributing to an increase in urban rat populations.

So, how did the study authors measure the growth in rat populations? By counting rat complaints reported by residents.

It uses these complaints to compare rat populations in different cities, which is the study's first major problem. The data don't allow for an apples-to-apples comparison. In San Francisco, for example, the authors examined the trend in all pest complaints, including those involving rodents and insects, from 2010 to 2022. In Boston, only actual dead rats or rat bites were included. In Dallas, the trend was estimated from 2013 to 2019. Some cities changed categorizations and added or eliminated categories over time.

Several of the incidents categorized by the city of Cincinnati as rat complaints were actually about roaches, bedbugs, cats, dogs, raccoons, and mice, based on the information in the description field. For one complaint, the only description provided was, "Tenant is pregnant," so it may or may not have had something to do with rats. They were all included in the study.*

If your data mixes apples and oranges, you'll get meaningless results.

The problems with the underlying data alone would render the study's findings invalid. But we're just getting started.

The next problem is that rat complaints aren't a good measure of rat populations. While the authors acknowledged the limitations of their approach, they also cited three studies (1, 2, 3) to support the claim that rat complaints accurately measure the growth of the rat population.

However, these three papers actually say—as one did explicitly—that "citizen complaints for rats…were bad predictors of measured rat activity."

They point out that there were more rat complaints in areas with fewer rats because one rat can cause alarm but when rats are common, people don't bother notifying the city.

They also found that in places with more people, there could be fewer rats and more complaints; after all, it's people who complain, not rats. Also, people in wealthier areas complained more frequently than those in poorer areas.

An important but more technical criticism is all three papers discussed only changes in individual cities over time, which does not logically tell us anything about comparing different cities over fixed time periods, especially since the time periods varied among cities, and the cities administered and counted complaints differently.

The misrepresentation of the three studies that the authors referenced illustrates a common problem in academic papers—researchers will cite sources that say the opposite of what they claim. And the peer reviewers for this major science journal apparently didn't bother to check.

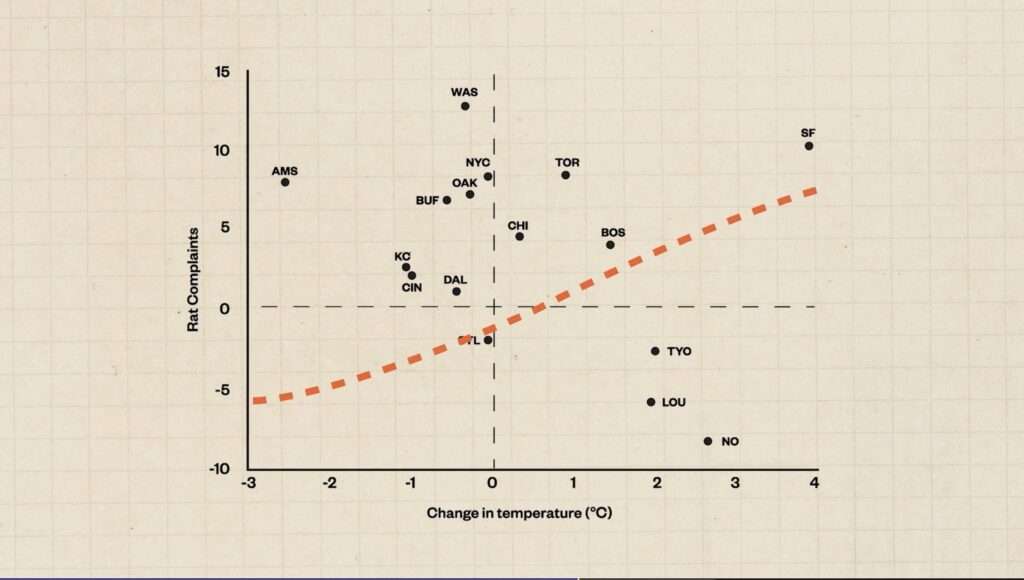

Next, the authors took all this unreliable data and compared it to changes in temperature in 16 cities. This chart illustrates the authors' comparison of growth in rat complaints to the change in average annual city temperature over the study period.

Note that the chart doesn't show a positive correlation between more warming and more rat complaints. In three cities, temperatures rose and rat complaints fell. And in the eight cities that cooled, there were more rat complaints. The only city with a clear association between rising temperatures and increased rat complaints was San Francisco.

The authors did acknowledge this in the paper, finding "no correlation between monthly mean temperature" and increasing rat populations, and that "the trends in rat numbers were not linked to…mean minimum temperature in each city."

Yet, the journalists who trumpeted the study in articles and on local TV news reported the opposite. Why did they get it backward? Most of the fault lies with the journalists who didn't bother reading the study. However, the authors made a different claim in the study that was easily misunderstood.

It's worth noting that University of Richmond biologist Jonathan Richardson, a coauthor of the study, was gracious with his time while I was working on this video. He responded to my email and was very helpful in resolving some issues I had in replicating the study results, which is unfortunately rare among researchers. However, his careful wording when talking to the media helps explain why the study was so widely misinterpreted.

In a video interview about the study, Richardson said, "what we found is that cities that are experiencing warmer climate trends, so temperatures that are increasing over time, also are experiencing the fastest increases in rat population growth."

Note the phrases "climate trends" and "over time."

What he means is he's correlating rat populations today with events over a century ago. But if he had put it that way, journalists might start to question what this finding has to do with current temperatures.

This is a ridiculous thing to measure. Consider Tokyo, one of the 16 cities included in the study. The authors tabulated rat complaints from 2008 to 2021, and then compared that data to rising temperatures in the entire country of Japan since the year 1901. They found a correlation. So what?

Were the rats smart enough to measure country-wide average temperatures and remember them for over a century when deciding in 2008 to start causing enough of a ruckus that Tokyo residents would file more rat complaints with the city? Are the rats secretly climate change activists?

They would need quite a historical perspective. Temperatures in Japan did increase from 13.7 degrees Celsius in 1901 to 17.0 degrees in 2007. However, by 2008, when rats began their 13-year campaign to scare humans into filing more complaints with the city, the warming had started reversing. During the study period, from 2008 to 2021, Tokyo's mean temperatures fell from 17 degrees to 16.6 degrees.

The authors compared regional temperature changes since 1901 with recent rat complaints for all 16 cities. This correlation was the study's only significant finding, and it's meaningless.

Global warming will not bring a rat apocalypse, and these disease-carrying pests will not be swarming the sweltering streets of our major cities anytime soon. Any more than they already are, at least.

Linking rats and global warming yields sensational headlines for advocacy journalists who want to sound the alarm about climate change. But this study used shoddy data, was presented in a deeply misleading way, and the media should have paid it no attention whatsoever.

*UPDATE: The original version of this article didn't make it clear that the city classified the complaint involving a pregnant tenant as "rats, in a building."

- VIdeo Editor: Cody Huff

- Graphics: Adani Samat

- Audio production: Ian Keyser

Show Comments (105)