Do Libertarian Voters Actually Exist? Yes, and in Droves [Reason Podcast]

Cato's polling director Emily Ekins says as many as one in five voters can be identified as libertarian.

Everyone nods their heads when pundits and pollsters talk about conservative votes, liberal voters, and populist voters. But do libertarian-leaning voters actually dwell among the American electorate? A new analysis of the 2016 election concludes that libertarians are as mythical as the hippogruff. Using a variety of survey questions about cultural and "identity" issues and economic policy, New America's Lee Drutman basically says no.

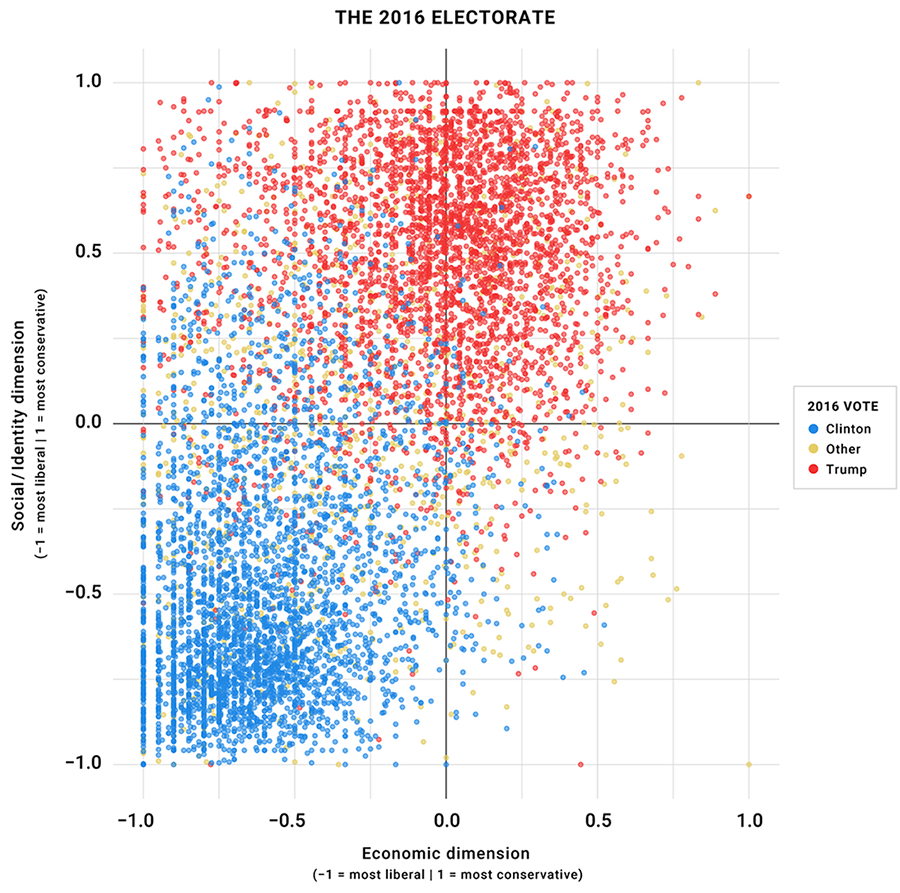

Dividing voters into one of four groups, he finds 44.6 percent are liberal ("liberal on both economic and identity issues"), 29 percent are populist (liberal on economic issues, conservative on identity issues), 23 percent are conservative (conservative on both economic and identity issues), and less than 4 percent are libertarian (conservative on economics, liberal on identity issues). According to Drutman, Donald Trump won by picking up virtually all conservatives and a good chunk of populists, while Hillary Clinton only pulled liberals. What few libertarians there are just don't amount to any sort of force in Drutman's take (see that empty lower-right-hand quadrant in figure). Drutman's piece gave rise to a number of pieces, almost all from the left side of the political spectrum, crowing that "libertarians don't exist" (in Jonathan Chait's triumphalist phrasing at New York magazine).

Not so fast, says Emily Ekins, the director of polling at the Cato Institute (a position she previously held at Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes this website). Libertarians are real, she documents in a new article, and they're spectacular. Responding to Drutman's elimination of libertarians as a meaningul voting block, she emphasizes that his finding is an outlier in the established research:

It depends on how you measure it and how you define libertarian. The overwhelming body of literature, however, using a variety of different methods and different definitions, suggests that libertarians comprise about 10-20% of the population, but may range from 7-22%. (Emphasis in original.)

In the newest Reason Podcast, Nick Gillespie talks with Ekins not simply about the errors of Drutman's analysis (he also finds many more liberals than most researchers) but about the sorts of issues that are motivating libertarians and other voters, especially Millennials. In the podcast, Ekins stresses that economic issues and concerns tend to drown out all other factors when it comes to voting patterns. But, she says, there are periods during bread-and-butter issues recede and cultural and symbolic issues come to the fore. We may well be in one of those periods despite weak to stagnant economic growth because most people's standards of living have held up (even if economic anxiety is on the rise). This is, she says, especially true among voters between 18 years old and 35 years old. That's mostly good news for libertarians. Millennials, she tells Gillespie,

libertarian on social issues and civil liberties except for one issue: free speech issues. I think this is something that we're going to need to keep an eye on… [Y]ounger people are more supportive of the idea that some sort of authority, whether it's the college administrator or the government should limit certain speech that is considered offensive or insulting to people.

Audio production by Ian Keyser.

Subscribe, rate, and review the Reason Podcast at iTunes. Listen at SoundCloud below:

Don't miss a single Reason podcast! (Archive here.)

This is a rush transcript—check all quotes against the audio for accuracy.

Nick Gillespie: Hi I'm Nick Gillespie and this is The Reason podcast. Please subscribe to us at iTunes and rate and review us while you're there.

Today we're talking with Emily Ekins she director of polling at the Cato Institute, a position she also previously held at The Reason Foundation, the non-profit that publishes this podcast. Emily also holds a PhD in political science from UCLA and writes on voter attitudes and millennial sentiments towards politics and culture.

Emily Ekins, welcome.

Emily Ekins: Thank you for having me.

Gillespie: A recent analysis of the 2016 election results by the voter study group at the Democracy Fund concluded that there were essentially no libertarian voters. By that they were identifying it as people who were socially liberal and fiscally conservative. Instead the study found that most voters fell into a liberal progressive camp that was liberal on economic and on identity issues. Things like immigration, things like Muslim sentiments towards Muslims, gay marriage, things like that. It found that most voters fell into a liberal progressive camp or populist group that was liberal on economics but conservative on identity politics or conservative on identity issues and conservative on both economic and identity issues.

The conclusion was Trump won because he won conservatives and populist while Hillary Clinton only polled liberals. For me, and I suspect the big point of interest for you also, was that the author, the political scientist Lee Drutman found that just 3.8% of voters fell into the libertarian group. There's a scatter plot, there's a very lonely quadrant there that is supposedly where libertarians don't exist. It led to a lot of people talking about there is no libertarian vote, we've been telling you this all along. Is Drutman right that there are essentially no libertarians in the electorate?

Ekins: Well first I'll say this. That I actually worked with Lee Drutman on this broader project which is part of the Democracy Fund voter study group. We feel that a very large longitudinal survey of 8,000 voters right after the election. Then several of us actually wrote up our own reports analyzing the data. Lee wrote a paper, I wrote a paper and I have a lot of respect for Lee Drutman and his research.

Gillespie: Okay, now stick the knife in. You have a lot of respect for him and so while he's beaming and looking up at the sun.

Ekins: I would say that on this particular aspect of his paper where he says that there's only 3.8% libertarians, I would say that that is inconsistent with most all other academic research I have ever seen on the subject. He also found that about 45% of the public fell into this economically liberal and socially liberal or identity liberal quadrant. Again I've never seen anything that high in the literature and I've surveyed most all of it that's really looked at this question.

I would say that's it's very inconsistent, you want to know what's going on. I think what happens is that people use different methods to try to identify the number of liberals, libertarians, conservatives and populists. They use different methods, they also use different definitions. What does this mean to be a liberal or a libertarian? The method, the question that they used to try to ascertain if you are a libertarian also differ.

In this instance one of the dimensions, you said that, typically when we try to identify libertarians we look at people who are economically, some will call it economically conservative or others will say less government intervention in the economy and then socially liberal. That's not exactly how his methodology worked. That that second dimension wasn't really about what gay marriage and legalization of marijuana, those types of social issues, it was about identity and he used a battery of questions that are very commonly used in academia but they're very controversial. They're used to determine your attitudes towards African Americans and racial minorities. These questions are problematic and I think that's part of the problem.

I could give you one example. One of the questions, it's an annoying question. It should put off most people but the question goes something like this, do you agree or disagree with the following statement: the Irish, the Italians, the Jews overcame prejudice without any special favors, African Americans should do the same. I think most people who hear this think, Ugh, why are we talking about groups? We're individuals. The problem is if someone who, if someone believes that no one should get special favors then they're going to probably agree with that statement. However if you agree with that statement you're coded as racist. Or not in the liberal direction shall we say.

Gillespie: Would you end up as a conservative or a populist?

Ekins: Those people are probably going to get pushed into the conservative or populist buckets. Essentially if you were to be a libertarian with this analysis, you would want less government spending, lower taxes, less government involvement in health care but also want government to, quote, give special favors. It's a very bizarre combination of attitudes that I'm unfamiliar with in the literature.

Gillespie: That reminds me of I know in the old Minnesota multi-phasic personality inventory which is still used in various ways. But back in the 40s and 50s if you were a woman, among the questions they would ask would be like, "Do you like reading Popular Mechanics or do you like working with tools?" If you said yes, she would kicked over into a lesbian category because that was obvious signs that there was something not right with you. What you're saying then is that the actual, more than in many things, you really need to look at the way in which the models are built and executed to figure out because different researchers have different definitions.

I know in your work you've written recently at the Cato website, at cato.org, about how typically libertarians come up as about 10% to 20% of the electorate and that the wider range is 7% to 22%. The fact that somebody comes up with a new and novel finding isn't, it doesn't mean they're wrong, but it means you really pay attention to see what's going on. How do most studies define libertarians and is the 10% to 20% any more accurate than the 3.8%?

Ekins: I looked at the literature, the academic literature on the subject about how do we identify these groups. There's different methods that are used. One simple method that I would say, is not as good of a method is just ask people to identify themselves. A lot of people don't they're libertarian when they are and a lot of people think they're libertarian when maybe they're not. That's not the best method. But if you do that you get about 11% or so who will self identify as libertarian on a survey.

A better method that academics often use is very similar to what Drutman used in his paper which is to ask people a series of public policy questions on a variety of different issues. Now the next step is where you can diverge. I would say the gold standard from there is to do a type of statistical procedure called a cluster analysis where you allow a statistical algorithm to take the inputs of those questions and identify a good solution about how many clusters of people are there in the electorate.

Stanley Feldman and Christopher Johnson did exactly this. I would say this is probably the gold standard. What they found was 15% were libertarian, they defined that as they tended to give conservative answers on economic questions or the role of government and the economy and gave more liberal responses on social and cultural issues. That's a very common way to do it. They found 17% were conservatives so not much different than libertarians. Slightly more were liberal, meaning economically liberal and socially liberal, 23%. They found about 8% were populist.

Now that not 100%. They found two other groups of people as well which it think also speaks to how interesting their analysis was, they found these two groups really didn't have strong opinions on economics but they differed on whether they leaned socially liberal or socially conservative. That actually tells us a lot. It fits well with what we see in American politics is that there are a lot of people out there that really don't know much about how the economy works but they do have an opinion when it comes to social and cultural policy.

Gillespie: How does these typologies of voters, how does it square with somebody like the political scientist Morris Fiorina who has for a couple of decades, at least, has been arguing that when we talk about culture war in America, and by that he means polarized politics and he grants that politics is very polarized and it's getting more polarized partly because the nominating processes for candidates that run for public office are typically in the hands of the most ideologically or dogmatically extreme members of various parties. He says when you look at broad variety of issues, whether it's things like abortion, whether it's drug legalization, whether it is immigration that there's oftentimes there's a broad 60% or more agreement or consensus so that we're actually one of the things he says is that our differences are routinely exaggerated and our agreements are typically ignored. Does that make sense? How does that match up with what you're talking about here because most people who do voter analyses talk about the things that separate voters rather than the commonality.

Ekins: It actually is very consistent with what the data suggests. Also if you're to look at my post at cato.org, the first chart in the post, I graphically display where the people live. Where are the libertarians and the conservatives and the liberals, if you were to plot them in an ideological plane, like the Nolan chart, on economic issues, social issues.

Gillespie: That's the world's smallest political quiz. Essentially it's a diamond shape that is made into quadrants. You're either more libertarian or more authoritarian from top to bottom.

Ekins: Yes. It's the same idea. What I did in this graph is plot where all the people live ideologically. What you see is it's a big blob. There is no structure meaning, there aren't just these, the story of polarization which does seem to be true at the congressional level, people who are elected to political office. But of the regular people of America, if polarization was happening and in Mo Fiorina, if he were wrong, then you would just see these two groups of people separated from each other on this plane. But that's not what it is. We see people are just randomly distributed. Meaning there are people with all different types of combinations of attitudes and the way our politics actually manifests is how we organize those people into, how those people organize themselves, I should say, into interest groups, into advocacy organizations, into businesses and then ultimately into politics. The way it is now, with Democrats and Republicans, it's by no means the only organization of politics that we can have.

Gillespie: Is there a sense and certainly I feel this and Matt Welch my recent colleague and I have written a book about it, but that part of what we're witnessing and it's hard to believe we're in the 2017, we're well into the 21st century but we're kind of stuck with these two large political groupings that go back to before the Civil War and that the groups that they were originally, and they get remade every couple of decades, but the groups, the conglomeration of voting interests that they once served, say even in 70s or 80s have fallen apart because this, to go from your blob on the Nolan chart to Democrats and Republicans in Congress if you're pro-abortion you have to vote for a Democrat and if you vote for a Democrat that means you're also voting in favor of certain elements of affirmative action or immigration policy.

If you're a Republican and you don't want people to burn the flag it also means you also have to be for lower marginal tax rates. These are things that really don't have any necessary connection. Is that the parties are describing or they're appealing to fewer and fewer people but you still have to vote for one or the other.

Ekins: Yes and that's probably contributed to the rise of the independent voter as well documented in your book. Also political scientists have shown that it's not just unique to US but most countries that have a political system similar to ours have what is equivalent to their congress, or their parliament divided along economic issues. In United States, this is by no means always true, but typically speaking, when people vote, they tend to vote along their economic interest, their economic issue positions if that makes any sense. All the social issues or at one time race became a second dimension in American politics. When these other issues have come out, then people are stuck, if they are out of alignment with their party on maybe social issues but are in alignment on economics the forces tend to have them voting along the lines of economics. That seems to be true not just in the US but other countries.

Gillespie: That explains libertarians voting oftentimes, self-identified libertarians or people in the libertarian movement aligning with the Republican party rather than the Democratic party because most of the people, I suspect, most of the people I talk to that I know at Cato and certainly at Reason are askance that they're not happy with Republican positions on a variety of science issues, on a variety of social issues for sure but they end up voting because they say, economics is more important.

Ekins: Yes, that seems to be what happens. But to some extent that is changing. There are periods of time where another dimension rises up like racial issues in 60s. Civil rights became so important some people were willing to say, I'm not going to stand with this party and allow it to continue doing what it's doing. It forced the party to change.

Gillespie: How does immigration fit into this? Because in Drutman's analysis it seems that immigration is a big, is one of those inflection points or hotspots. It becomes very interesting to me because Hillary Clinton when she was running as senator for the Senate in New York was very explicitly anti-illegal immigrant, she said she was against giving them drivers license. Bill Clinton forced the Democratic party platform in the 90s to be very hostile to immigration in general but especially illegals and one of the big pieces of legislation that he signed, actually on welfare reform in 90s and this is not necessarily a bad thing, but made it illegal immigrants and even legal immigrants for the first five years to be cut off from transfer payments, means tested transfer payments.

There's a sense that the Democrats are friendlier towards immigrants than Republicans and there seems to be some evidence for that at least in attitudes if not in policy because Obama was pretty terrible towards immigrants. But Mitt Romney was even worse. My larger question or I guess there's two questions here. One is something like immigration, it's not exactly clear how different the parties are in practice but then it's also, how much does it matter to voters whether or not, they might feel very strongly about immigration but it might be the 10th issue that they actually vote on. It doesn't even really come into play. How do you measure the intensity of a voter's belief in a particular topic and how that actually influences who they pull the lever for?

Ekins: There's a lot there. The first thing I would say is that there is a lot of posturing when it comes to immigration policy. Like you said, in many ways there aren't significant differences between many Republican and Democratic lawmakers when they, in their actual positions on immigration. But the posturing is different. Talking about self-deportation, that immigrants must learn english. Again it's not to say, most Americans to be honest would prefer immigrants learn english, it's not like that is so controversial, it's the way that it is said. If you're very first thing is about we need to secure the border and then second then we need to deal with X, Y and Z immigration issue. It gives the impression to people who are themselves immigrants or their children or friends of immigrants, are close to the immigrant experience, they get the very strong impression that they are not welcome. That is hugely important in how people are voting and that's why Democrats appear to be the pro-immigration party more so than Republicans. There are some policy differences like DOCA and things like that. But posturing is hugely important.

Generally speaking, I would say immigration hasn't been the highest priority when it comes to how people vote but data coming out of the 2016 election that I find very compelling and that we worked on as part of the Democracy Fund voter study group, suggests that immigration attitudes were by far what made this election and voting for Donald Trump most distinctive. It's not to say that people changed their minds, they don't seem to have changed their minds but rather these were concerns that they already had and they were activated by the rhetoric of the campaign. These were concerns people had, most Republicans and Democrats weren't talking about it in a way that people could really relate to then Trump comes in and just blows the lid off of it. Without nuance or without sophistication about the delicate issues that are at play here and people were so relieved and validated to have someone talk about immigration in the ways that they thought of if, they became very devoted to him. That meant …

Gillespie: I'm sorry, go ahead.

Ekins: I was going to say, and that meant other scandals that came out during the course of the campaign did not matter as long as he continued to validate feelings on immigration.

Gillespie: In the Drutman analysis, part of it was that he sees the Democratic party as basically pretty supportive and in line behind liberal economic policies and liberal identity policies. He identifies two different groups within the Republican party that Trump appealed to. One are traditional conservatives and Republican voters who are conservative on social issues and also say they're conservative on economic issues. But then populists, I guess populists he defines as people who are into big government, populists like farms subsidies, they like business subsidies, they like subsidies for jobs and the idea that the government will take care of them against the, whether it's Islamic terrorists or big business or rapacious interests. But also, but they're conservative on these identity issues. Trump in a way, in that rating he was able to get the populists who might have voted for Obama in 2012 but definitely were not going to vote for Hillary because she seemed to be, she's part of the establishment, she doesn't care about them, she's a New York elitist. Is that accurate?

Ekins: I think that is. Obama had an economic message that resonated with these voters. Hillary Clinton didn't seem to give the impression that she cared much about them at all. She thought, "Oh, demography is destiny, we no longer need voters that come from certain economic and other types of strata in the electorate." And she didn't talk to them. Obama did and it served him well.

Gillespie: The joke was that she went to Chipotle more often during the 2016 campaign than Wisconsin. And you assume if you're a displaced or you feel like you're a displaced factory worker in northern Wisconsin and somebody's going to Chipotle you're not going to identify with them particularly strongly.

Ekins: Yes, that true. Also a lot of people have argued that Donald Trump is basically a Democrat. We was for years and he gave lots of money to Democrats. He's basically a Democrat but he is very suspicious of immigration which is right now out of line with the Democratic party.

Gillespie: Right, and he ran against the swamp in DC and all the people who had been living there or attached to it for years. Even though his economic policies were indistinguishable, it's just in the news that the Carrier air conditioning plant in Indiana that he had made a big stink about, getting them to not move to Mexico and of course all the jobs are going to Mexico anyway but it was a very interventionist, I don't even know that it's Democrat versus Republican 'cause Republicans love business subsidies in their own way but it was very populist certainly that the president was going to force big business to heel and to do what is right for the common American worker.

Your Cato colleague David Boaz who has written widely and wonderfully about libertarianism and you've done some work with him, about a year ago he asked Gallup to follow up. And I'm curious about this because I like this story a lot. He used Gallup data to break people into four categories: conservatives, liberals, populists and libertarians. He found using a question that keyed off of, that Gallup itself uses, to talk about political ideology, he found that libertarians, people who tended to be socially tolerant and in favor of small government were the single largest ideological block, 27%. Then there were conservatives at 26%, liberals at, I think it was 23% and populist at 15%. Does that work for you? In general that method and those results, do you find those are worth keeping in the front of our minds?

Ekins: I would say that's a little bit on the higher end of the numbers that I've seen. But that's a product of the method of using, I believe, they were using two questions. Something on an economic issue, role of government in the economy and then traditional values and you just look at who of the respondents said that they wanted small government and government not to promote traditional values.

That's a fine way to quickly segment the electorate but I probably wouldn't put too much stock in there being a difference between 27% and 23%. I do think though that that populist, the populist bucket if you will, Paul Krugman called them hardhats, some people call them communitarians or statists. They do seem to be a smaller segment of the electorate and think that they're going to be getting smaller as people do become more socially liberal over time.

Gillespie: Is there a sense, I realize this might be outside of your realm of expertise or interest, but part of thing as mediocre as the economy has been in the entire 21st century, we've been well below 2% annual growth which is something that we used to take for granted or even something closer to 3%, but the fact is is that most people's material lives are pretty good and they're getting better in terms of people have food, clothing and shelter and those things tend to get better over time. Are we moving more into a realm where the more symbolic issues or what you talked about as posturing or what we might call identity issues, are those going to dominate more and more? You had mentioned that civil rights was a huge factor in the 60s, obviously there was foreign policy as well as economic issues going on but are we more in a symbolic space now where it's not about whether or not people have enough to eat. Nobody's going to win election as president again by promising a chicken in every pot. But are we in a post-economic phase of political identity?

Ekins: I think that's a very interesting question and it reminds me of Brink Lindsey's book Age of Abundance with the idea being that economic wealth essentially allows us to have, I'll just make this up here, luxury ideological goods. If you have what you need then you can focus on other things that you believe in truly from a political standpoint that are not related to the bread and butter of jobs, housing, food, things like that. Certainly we have seen that. The introduction of social issues and cultural issues as being a second dimension of American politics emerged about the time that economic prosperity and growth really took off.

But I would say this, as a caveat to that, in the Democracy Fund voter study group that we worked, our group more broadly, two authors Ruy Teixeira and Robert Griffin at the Center for American Progress, they did another paper and what they found, was I thought very interesting, that individuals who were struggling economically or said they were struggling economically in 2012 were significantly more likely by 2016 to have become more anxious and concerned about immigration and wanting to restrict immigration. Let me just, if I'm saying that clearly enough here. People that had worse economic situations in 2012, four years later disproportionately turned against immigration. Why is that?

It does seem to me that to some extent this isn't just purely an ideological luxury issue that many people perceive it to be economic even if it might not be, people think it is.

Gillespie: Right, and it speaks to a whole host of, beyond any question about economics and as good libertarians I suspect we agree that even illegal or maybe especially illegal immigrants are a boon to the economy to the culture et cetera but regardless of the economics of it, the idea that you are a person in America who has been made redundant or irrelevant in a particular economic moment and you're pissed. Immigrants are the ultimate place where you can focus your anger and ire. Somehow they are getting something that you cannot anymore.

Ekins: Right. There definitely seems to be something going on there. It was a theory that a lot of people had that I think to Teixeira and Griffin really showed that empirically.

Gillespie: Now of course Teixeira also has been talking about the oncoming iron clad Democratic majority for a decades really. And we all do this where we, going back to Kevin Phillips who had the coming Republican majority at a point when the Republicans looked like they were about to go out of business. He was right for a while then was wrong, right again. One of the things that Gallup and I guess Harris used to do this too, where they would ask people to self-identify both as Republican and Democrat and it was always that there were always more Democrats, people who would identify as Democrats than Republicans but there were always many more people who would identify as conservatives rather than liberal and in most of those things, the self-identified liberal group would never get really more than about 20% of the electorate going back to 1970 and conservatives would be in the 40s, sometimes almost the 50s.

Yet over the past half century Republicans keep winning elections, particularly at the state and local level and Democrats keep losing. Is there any worthwhile way of digging through that where there are more Democrat, people who identify as Democrats but there are more conservatives but that's why Republicans win elections? Or is this just these are categories that are so loose that they really don't tell us anything?

Ekins: Well I think the first point, it brought to mind a phrase that I think you hear a lot of people say. Where they say, "I'm a conservative, I'm not a Republican." That distinction matters to a lot of people. But as political science research has shown, over time the parties have become more aligned with a particular ideology. Conservatives are more likely to be Republican and liberals more likely to be Democrat than in the past. That doesn't mean though that people are comfortable with the words liberal. For some reason the word liberal has been a bad word and so a lot of people who really are just liberal Democrats would say, "I'm a moderate Democrat," or "I'm more conservative." That's just more semantics. I think that's why we want to ask them, what do they think about public policy? That's the best way to know where people go.

I don't know how this maps onto though, the fact that Republicans have been doing better at winning these state and local elections. Other than the idea that they are more organized than the Democrats are right now. Right now Democrats seem to be very focused at the federal level and protests and more like expressing themselves. For instance in Los Angeles it's my understanding that, wasn't there 700,000 people who turned out for the women's march and it was only a couple hundred thousand showed up for the local elections? In the same month.

Right now it seems like Democrats are more focused on expressing frustration and anger and Republicans have been more organized and as a result they have been winning more elections at the state and local levels.

Gillespie: Let's talk about millennials. A few years ago you did a fantastic survey for Reason and the Roop Foundation about millennials and you've continued to work that ground. Are millennials, are they more or less libertarian than GenXer's or Baby Boomers? You foregrounded a lot of this and I guess we actually wrote something together about this that I'm now in my dotage I'm remembering. It seems that millennials use a different language to talk about politics. Are they, and a lot people confuse that for them being socialists, literally socialists, a lot of millennials love Bernie Sanders. Millennials, at least going back to the Obama years, which would have been the first elections that they could have voted in, overwhelmingly vote for Democrats at the presidential level. What you're take on millennials? Are they more or less libertarian than people in the past or are they more or less liberal or progressive?

Ekins: It's hard to answer that question. I would say that GenX in some respects seems to be the more libertarian generation of the groups. With millennials what we found is that they don't seem to stand out on economic policy so a lot of people think that they're all socialists because they like Bernie Sanders. That actually doesn't seem to line up with where the facts are. But they came of a political age, more or less, when Bush was either president or on his way out and the Republican party brand was in shambles and Obama was an incredibly popular brand and figure. So obviously the messengers that they trust, President Obama, John Stewart of the Daily Show, the messengers that they trusted really didn't tell them anything about free market economics. It's actually maybe almost surprising that they're not more statist than they are.

It's on the social issues that we see a difference and that they are more libertarian on social issues and civil liberties except for one issue. Free speech issues, I think this is something that we're going to need to keep an eye on. Where younger people are more supportive of the idea that some sort of authority, whether it's the college administrator or the government should limit certain speech that is considered offensive or insulting to people.

Gillespie: Wow. You're working on a study about that, is that correct?

Ekins: That's correct. It should be out in September.

Gillespie: Wow. That is obviously something to look forward to. You also recently identified in a, again at cato.org, five types of Trump voters. What are they and how are they relevant to analysis?

Ekins: Yes, this is also part of the Democracy Fund voter study group, we talked about them quite a bit during this podcast. I wrote a separate paper that did a type of statistical analysis, a cluster analysis of the Trump voters. Because a lot of folks have had this tendency to talk about the Trump voter as though it's one type of person, that voted for him for one particular reason. This statistical analysis that I ran, found five different types of Trump voters and they are very different from one another. On even the issues central to the campaign, immigration, matters of race and American identity. They're even very different on the size and scope of government. In way it's amazing that they're all in one coalition here. I could go over some of those groups if you are interested.

Gillespie: Yes, please do.

Ekins: The first group I'll mention, I call them the American Preservationists. They are the core Trump coalition that put him through the primaries. They're not the most loyal Republican voters though. They're more economically progressive, they're very concerned about Medicare, they want to tax the wealthy some more but they are very, very suspicious of immigration both legal and illegal. They have cooler feeling toward racial minorities and immigrants. They fit the more typical media accounts of Trump voters. What really surprised me about this group is that they were the only group that really felt this way and most likely group to think that being of European descent was important for being truly American. A very unusual group of voters. But they comprised about 20% of the whole coalition.

Gillespie: Wow, and they're highly motivated and intensely active. I recognize them daily in the comment section at Reason.

Ekins: Yes. But again 20% of the coalition.

There was another group that I think would really surprise you that existed in the same coalition. I call them the Free Marketeers. They actually comprised a larger share, 25%, and in many ways they're the polar opposite of the American Preservationists. They were the most hesitant Trump group. Most of them voted for Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio in the primaries and they said that really their vote was against Hillary Clinton. As opposed to being for Trump. These are just, as the name implies, small government fiscal conservatives, they have very warm feelings towards immigrants and racial minorities. They're the most likely group to support making it easier to legally immigrate to the US. They're very similar to Democrats on these identity issues. They're polar opposites to the Preservationists.

Gillespie: How do they, I guess I know the answer to this which is it's Hillary Clinton. Because Trump was so out there in terms of trade protectionism and forcing businesses to his will, he did not seem to be at all a free trader or a free marketer.

Ekins: Not at all but Hillary Clinton, besides trade didn't seem to be one either. I think they disliked her so much it seems like they, that's why they voted for Trump. But they also have the most in common with the third party voters who voted for Gary Johnson. If they weren't voting for Johnson or staying home, they were in this bucket.

Gillespie: You did have one group in your schematic that were, I'm sorry I'm blanking on the title now, but it was the Disinterested or Disaffected voters. Is that right?

Ekins: Yes, they were a small group, The Disengaged. They didn't tell us much about their politics, they're the type of people that when they take surveys they just don't have many opinions but the opinions that they did have were, they were suspicious of immigration and the felt the system was rigged against them. That was really a more common thread. It's not a thread that all the Trump voters shared in common but there was a bit more suspicion of immigration which make sense because that was a major part of Trump's campaign rhetoric.

Gillespie: Right. That also calls to mind the Drutman analysis where this idea of the system being rigged or the system not working anymore. If not, the system is either actively hostile to you or it just is just totally incompetent in delivering basic things. Like I work hard so I should have a good life, this system isn't doing that anymore. Is that, which also linked Trump and Bernie Sanders 'cause Sanders was running as an outsider and oftentimes in terms that were almost indistinguishable from Trump. Is that really the battleground now of whether or not you are working or are supporting the establishment or are you a marker of the system or are you actively attacking it? Is that the real front of American politics?

Ekins: I don't quite see it like that. I did find a group that fit that exactly. Their name is just what you'd expect. I call them the Anti-Elites. They fit just what you're talking about. They don't really align with Trump that much on immigration issues, they're a lot like Democrats on economics and immigration but they really felt like the system was rigged against ordinary people like themselves. And the establishment versus the people. For two of the five clusters, and they're the majority, of the Trump voters, the Free Marketeers and another group that I haven't mentioned yet, The Staunch Conservatives.

They're just more conventional Republicans. They don't think the system is rigged. They don't think that people take advantage of you. They think that they have agency and that they through their votes can change the political process, which is the exact opposite of the Preservationists that I mentioned and the Anti-Elites. Which fits that narrative that you're talking about. Now that narrative really does a good job at explaining more of the vote switchers, the people who voted for Obama in 2012 and switched to Trump in 2016, they do feel that way. But that doesn't explain all of the Trump voters.

Gillespie: How common was it for people to have voted for Obama and then to have switched to Trump.

Ekins: I had the number almost in the top of my head today. It was about 6%, something like that. Sizable enough obviously. But there were also voters, Republicans who voted for Romney who switched and voted for Hillary Clinton or a third party. If I remember correctly it was slightly more Obama voters switched to Trump than Romney voters that left the Republican party. There's a slight net gain, but I think it's important for people to realize that for all the voters that Trump picked up, the Republican party lost a lot of voters too because of Trump.

Gillespie: Do we make a mistake, a fundamental mistake when we try to analyze political trends through presidential elections? Because they come once every four years, we had, this time around, we had the two least liked candidates in American history. Is it a problem if we key too much off of who wins the presidency? And we essentially, just as we started the 21st century, with a dead heat where a few thousand votes essentially separated Bush and Gore. We had this bizarre outcome where Trump lost the popular vote pretty sizably but won the electoral vote. To my mind that's not a constitutional crisis, it's a sign that nobody can get to 50%. Is it wrong to look at the presidential races as the way, to tell us where politics is going?

Ekins: I think you're absolutely right. People read way too much into presidential elections. If you recall after George W. Bush won in 2004, there were all sorts of magazine covers and books that would show red America being huge and then blue America, the coasting really small and the permanent Republican majority but then, then Obama won then it was demographics is destiny and it's going to be a permanent Democratic majority. Even still a lot of people have read, particularly I would say on the more Republican side of thing of over read too much into this Trump election thinking that, oh if only Republicans appeal on the way that Trump does that's how they win.

Here's what we know in political science. This might surprise some of the listeners here, but that economic variables for instance, how fast the economy's growing, what's the labor force participation rate as well as the current president's approval ratings. A couple of these structural variables predict almost every election outcome over the past 100 years. What that means, I'm not saying campaigns don't matter, they seem to have to matter in some respects. Maybe if you didn't run a campaign then you would just get blown out of the water. Assuming you've got two campaigns going, the structural variables seem to be hugely important.

They're not always right, they've missed three elections, one of them was Gore versus Bush, as you recall Gore did technically win the popular vote. These models seem to be pretty good. And throughout this entire election campaign I was telling folks, hey look at, I'm forgetting his name, excuse me. There's a few economists that do this Abramowitz did one of these models, Ray Fair at Princeton does a model. If you followed Ray Fair's model, he predicted a Republican win almost the entire election. I thought well, just about any Republican can win this election. I thought Trump might not be able to do that, there are outliers but he did pull it out, and I think part of the reason are these economic fundamentals.

Gillespie: Let's close out by talking about libertarians and their way forward for people who are libertarian voters, obviously Gary Johnson and William Weld for all of the tension and controversies within that campaign and whatnot, they had the best, by far the best results of any libertarian party candidate. But beyond the LP, with small L libertarians, what are the issues that libertarians are interested in that seem to give the most possibility of building meaningful alliances and pushing forward over the next couple of years? In the past it's been things like drug legalization, criminal justice reform. Certain aspects of immigration and free trade certainly. Gender equality and marriage equality. Are libertarians, where would you say, given their array of issues, where do those match up with most other groups where we might be able to build meaningful alliances?

Ekins: I think it's a great question but I think it's a hard question to really answer. I agree with you on most of those issues, that those continue to be key issues for libertarians particularly criminal justice reform, privacy issues. That's something that really wasn't on the radar in terms of issues until Edward Snowdon really it seems like. But I think another thing for libertarians to think about is thinking about Republicans and Democrats, and realizing that they do have shared interests with both groups. To try to emphasize what we as libertarians are for, not what we're against. I'll give you an example 'cause we're talking about healthcare a lot on the news.

I am for everyone who wants to have access to healthcare to able to get it. We live in a country where people have houses, they have access to food and they don't have the government running it. We have found a way that the markets provide these things then we do have a social safety net for those who hit hard times and need help, we have ways to fill those gaps but it doesn't require the government to run it all. When it comes to things like healthcare and other issues like that we are for all of these positive outcomes.

The question is what's the best way to do it? What I often hear is some of our libertarian friends talking about what we're against. Let's talk about what we're for, whether that be for criminal justice reform, whether it be for healthcare, whether that be for entitlement reform, drug reform and so forth. Let's talk about the end goals 'cause you think about it, I hear this coming from the political parties all the time. They tell you the outcome that they want to deliver you. Now they're wrong all the time but let's talk about the outcomes that we believe that a freer society that libertarian public policy can help deliver. Let's focus on the positives.

Gillespie: All right that sounds like pretty sage advice and I'll be very interested in September when your paper about free speech and millennials comes out because it may be, it'll be interesting to see what's the outcome you're proffering there. And then working to persuade millennials who are more likely to believe in constraints on speech. It sounds like a tough nut to crack but a really interesting one as well.

We have been talking with Emily Ekins, she's the director of polling at the Cato Institute and she is also a PhD in political science from UCLA and writes widely on voter attitudes and millennial attitudes as well.

Emily thanks so much for joining The Reason podcast.

Ekins: Thank you for having me.

Gillespie: For Reason, I'm Nick Gillespie, this has been The Reason podcast, please subscribe to us at iTunes and rate and review us while you're there. Thanks so much for listening.

Show Comments (166)