Steven Pinker Wants Enlightenment Now!

Pope Francis is part of the problem, nuclear energy is part of the solution, and libertarians need to admit that not every regulation will turn us into Venezuela.

America, observers are fond of saying, is the only country based upon an idea. That idea—that all men and women are created equal and have inalienable rights to life liberty and the pursuit of happiness—is directly informed by the Enlightenment, the movement that dominated ideas and culture in the 18th century.

But are we still an Enlightenment nation?

"The Enlightenment principle that we can apply reason and sympathy to enhance human flourishing may seem obvious," writes Steven Pinker in his new book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism and Progress. "I wrote this book because I have come to realize that it's not."

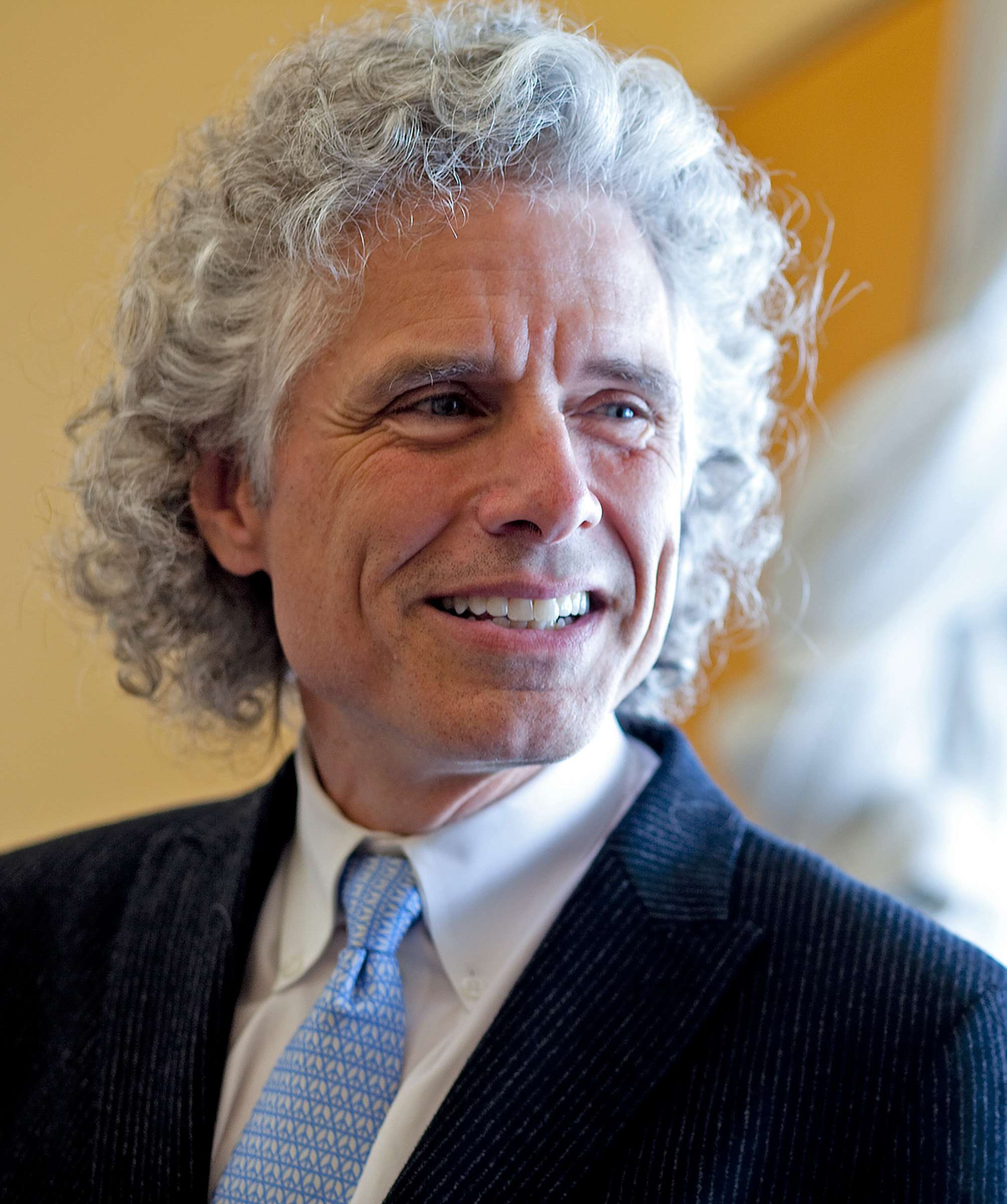

Pinker is a linguist who teaches at Harvard and is the author of The Better Angels of Our Nature, The Blank Slate, and How the Mind Works. He's been named on the top 100 most influential intellectuals by both Time and Foreign Policy.

In this wide-ranging interview with Reason's Nick Gillespie, Pinker explains why he thinks Pope Francis is a problem when it comes to capitalism, nuclear energy is a solution to climate change, and why libertarians need to lighten up when it comes to regulation. He also makes the case for studying the humanities as essential to intellectual honesty and seriousness even as he attacks that "cluster of ideas, which is not the same as the humanities, but just happens to have descended over large sectors of the academic humanities: "the deep hatred of the institutions of modernity, the equation of liberal democracy with fascism, the feeling that society is in an ever-worsening spiral of decline, and the lack of appreciation, I think, that the institutions of liberal democracy have made the humanities possible, made them flourish."

Produced by Todd Krainin. Cameras by Mark McDaniel and Krainin.

Subscribe to our podcast at iTunes.

The interview has been edited for clarity. Check all quotes against the audio for accuracy. For an audio version, subscribe to the Reason podcast.

Nick Gillespie: What comprises the Enlightenment?

Steven Pinker: My point of view identifies four things: reason, science, humanism and progress. Reason being the ideal that we analyze our predicament using reason as opposed to dogma, authority, charisma, intuition, mysticism. Science being the ideal that we seek to understand the world by formulating hypotheses and testing them against reality. Humanism, that we hold out the well-being of men, women and children and other sentient creatures as the highest good, as opposed to the glory of the tribe or the race or the nation, as opposed to religious doctrine. And progress, that if we apply sympathy and reason to making people better off, we can gradually succeed.

Gillespie: Why did the Enlightenment happen when it did?

Pinker: Because it only happened once, we don't really know and we can't test hypotheses, but some plausible explanations are that it grew out of the scientific revolution of say the 17th century, which showed that our intuitions and the traditional view of reality could be profoundly mistaken, and that by applying reason, we can overturn our understanding of the world.

Maybe the more proximate technological kickstarter was the growth of printing technology. That was the only technology that showed a huge increase in productivity prior to the Industrial Revolution. Everything else had to wait for the 19th century.

Gillespie: You talk about how basically between the year 1000 and about 1800, in many places people saw very little increase in material well-being.

Pinker: Yeah. Economic growth was sporadic at best. But printing technology did take off in the 18th century. Pamphlets were cheap and available, and broadsheets and books, and they got translated. They were circulated across all of the European countries as well as the colonies, so that the exchange of ideas was lubricated by that technological advance.

Another possible contributor was the historic memory of the wars of religion. That showed that dogmas about faith and scripture and interpretation and messiahs and so on could lead to tremendous carnage, and people thought, 'Let's not do that again.' These are all the ingredients. Which one was causal, we don't know.

Gillespie: A large section of the book documents the incredible material progress that we've made. What for you are some of the key markers that show the impact of Enlightenment thinking on our world?

Pinker: Certainly the conquest of hunger—the fact that now we've got this problem called obesity, the obesity epidemic. Historically, as problems go, that's a pretty good one to have compared to the alternative of mass starvation.

There still is hunger, especially in war-torn, remote regions, but by and large famine, as one of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse, has been tamed. And just sheer longevity, the fact that in the world as a whole, life expectancy now is 71. For most of human history, it was 30. Literacy—the fact that 90 percent of people under the age of 25 can read and write, when in Europe a couple of hundred years ago it was 15 percent. Less obviously, war has been in decline over the past 70 years or so, and crime has declined, even in a pretty crime-prone country like the United States.

Gillespie: But violent crime on a day-to-day basis started declining in the late Middle Ages, right?

Pinker: Yeah, so we can't credit the Enlightenment for that, because it was part of the transition to modernity. But it got a boost in the 19th century with the formation of professional police forces and with the more systematic application of criminal justice, and then in the 1990s and the 21st century with data-driven policing.

Gillespie: I found one insight related to criminal justice really interesting: talk about the idea of having a prison sentence or a sanction against a criminal fit the crime.

Pinker: Prior to the Enlightenment, there were gruesome criminal punishments for what we would consider rather trivial misdemeanors. Drawing and quartering, cutting a person open, ripping out his entrails while he was still alive and conscious.

Gillespie: I'm sure he was guilty of something, right?

Pinker: You know, poaching. Criticizing the royal garden. Then in the 18th century, Cesare Beccaria, who also coined the term 'the greatest good for the greatest number' (later picked up by Jeremy Bentham as a model for utilitarianism), argued for proportionality. Not so much to satisfy some cosmic scale of justice, but just to set up the right incentive structure. He pointed out that if you're going to apply the severest penalty to rather minor crimes, criminals could just say, 'Well, why stop at that? If I'm going to take a chance, I may as well go all the way—kill the witnesses, kill the witnesses' families, if I'm going to get the same punishment as just burglarizing the house in the first place.' It's a real rational, incentive-based argument.

Gillespie: You say, 'The world has made spectacular progress in every single measure of human well-being. Here is a second shocker. Almost no one knows about it.' Why don't we acknowledge that more?

Pinker: Some of it is that we have no exposure to it. Our view of the world comes from journalism. As long as rates of violence and hunger and disease don't go to zero, there will always be enough incidents to fill the news. Since our intuitions about risk and probability are driven by examples, the 'availability heuristic,' we get a sense of how dangerous the world is that's driven by whatever events occur, and we're never exposed to the millions of locales where nothing bad happens.

I think there's also a moralistic bias at work. Pessimists are considered morally serious. As Morgan Housel put it, 'Pessimists sound like they're trying to help you. Optimists sound like they're trying to sell you something.' We attach gravitas often to the doomsayer.

Gillespie: You beat up on Dr. Pangloss, the character in Voltaire's Candide who's fond of saying, 'This is the best of all possible worlds, so everything in it is perfect.' If you want to be a data-driven optimist—a rational optimist, in Matt Ridley's phrase—how do you prevent yourself from becoming Gillespie Panglossian? Because there's no question, compared to 500 years ago we're much better off, so stop complaining, you know?

Pinker: As Matt points out, Pangloss was a pessimist. An optimist thinks that the world can be much better than what it is today.

Gillespie: Yeah, and he has syphilis, so it's like, his world could be a lot better.

Pinker: Voltaire was really satirizing Leibniz's argument for 'Theodicy,' namely that God had no choice but to allow earthquakes and tsunamis and plagues, because a better world was just ontologically impossible.

[To keep from being a Pangloss, you should] stick with the data and notice that some things get worse. Right now, for example, the opioid epidemic is clearly an example. There have been fantastic setbacks: the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918–1919, World War II, the 1960s crime boom, AIDS in Africa. You've also got to be aware of low-probability but high-impact events such as nuclear war. Such as the possibility of catastrophic climate change.

Gillespie: Let's look at some of the groups that you see as anti-Enlightenment. The first one I want to talk about is the Romantic Green movement. What do you mean by that phrase, and who are these people?

Pinker: Well, my particular foil for that would be Pope Francis, and I know that arguing with a man who's infallible must be the ultimate exercise in futility.

Gillespie: That's why you have tenure, right?

Pinker: That's exactly right. This is the idea that humanity made a terrible mistake when it began the Industrial Revolution, that we've been raping and despoiling the environment, which has been getting steadily worse and worse and worse, and that we will pay the price in a dreadful day of reckoning.

Gillespie: Even if we did have 200 years of progress from 1800 on, everything's about to go to hell?

Pinker: Right. Or the progress that we've experienced so far is illusory, since we're breathing in carcinogens as we speak and since species are dropping like flies, so actually our situation is getting worse and worse and worse. This movement tends to be opposed to the technology-driven increase in living standards over the last couple of years. It tends to see humanity as a scourge on the planet. In the book, I acknowledge that concern with the environment certainly is a good thing, and we have the Green movement to thank for reminding us that there can be harms from pollution.

However, there is an alternative approach to protecting the environment, sometimes called ecomodernism or ecopragmatism, that acknowledges that pollution has been a price that we have paid for enormous benefits to humanity—more than doubling lifespans, emancipating slaves, emancipating women from domestic drudgery, emancipating children from farm labor and getting them into schools. Some degree of pollution is worth paying just as some amount of dirt in your house is worth it, because the effort to keep it perfectly clean would mean sacrificing everything else good in life.

Gillespie: It's not that the world exists merely for us to blow it up if we want to, but rather that a lot of the Romantic Greens don't seem to put any value on human flourishing.

Pinker: An example would be the implacable opposition to genetically modified organisms, which promise increased nutrition and in fact promise enormous environmental benefits—crops that need fewer pesticides, fewer fertilizers, less acreage.

Gillespie: Less water, less resources.

Pinker: Right. So paradoxically, that would be a case in which adherence to a Romantic ideology—what is natural is good, what is human-made is bad—actually can harm the environment.

Another aspect of ecomodernism is the recognition that affluence in general is good for the environment. When people are so poor that electricity itself offers a big leap in their living standards, they'll live with an awful lot of pollution in return for electric current coming out of their walls. Once you get a little bit richer, and you're starting to choke on smog and you can't see the horizon, then you're willing to pay for the pollution control devices that give you the electricity without all the pollution.

Gillespie: China 50 years ago just wanted enough to eat, and they were willing to industrialize without thinking about pollution. Now you're starting to see that as Chinese people get richer, they want cleaner air.

Pinker: Absolutely. The world's most polluted areas are poor countries. Poverty is the greatest polluter.

Gillespie: I would think neo-Marxists would say, 'Well, that's because the rich parts of the world are exporting their pollution to poor countries.'

Pinker: That's not literally true. Most of our pollution can't be exported because it's involved in the generation of power and home heating and so on. And a lot of the pollution in the developing world comes from burning wood or dung, especially indoors, and from contaminated drinking water.

Gillespie: Let's talk a bit about climate change. First and foremost, you believe that it's happening and that human activity adds to it, right?

Pinker: Yeah.

Gillespie: You talk about how there's a strong argument for nuclear energy if what you care about is how to get the most energy out of the fewest greenhouse gases. How did you come to appreciate nuclear?

Pinker: Partly from thinking through that we really do need scalable, abundant, affordable energy, particularly in the developing world. There's a moral imperative to allow India and China and Africa to enjoy the benefits that we've enjoyed from abundant energy. Nuclear energy doesn't involve burning anything, so it doesn't emit carbon, and a lot of our dread of nuclear energy is because it hits all of our cognitive buttons for the fear response: It's novel, we can imagine a catastrophe, it's man-made as opposed to natural. There are a few salient events that lodge in our cultural memory, mainly Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, and now Fukushima, despite the fact that the human damage in each case was trivial compared to what we tolerate day in and day out from burning coal.

Gillespie: I hadn't thought about it in these terms, but you mention that only 60 or 100 people died directly in Chernobyl.

Pinker: Yeah, and then there probably was a slightly elevated cancer rate, barely detectable.

Gillespie: So is this a case where we can imagine the disastrous outcome and that overwhelms the cognitive ability to talk about this stuff rationally?

Pinker: That's right, because the far greater number of deaths come from fossil fuels—from mining, from transporting, from the pollution. It just never happens all at once in a photogenic event. Coal kills, according to one estimate, about a million people a year, but that doesn't make the headlines.

Gillespie: You also note that France and Germany, which are countries that get a lot of electricity generation out of nuclear power, are moving toward getting rid of it, right?

Pinker: Germany most of all, and their carbon emissions have gone up. Because when nuclear power plants are taken offline, they're replaced by fossil fuels.

Gillespie: I guess part of the Romantic Green movement is this idea that you can get something for nothing. But if you wanted to use wind energy or solar panels, there's a vast amount of area that would need to be covered with these things in order to generate the type of energy we need.

Pinker: And also the wind is sometimes becalmed, and the sun doesn't shine at night. Even with the enormous penetration of photovoltaics, which is clearly a good thing, there's a limit to how much of the energy demand [solar] can assume, since a modern economy also has to provide energy at night, and there are long periods of time in which there's pretty thick cloud cover. If we need a fossil fuel backup, then it doesn't really help with reducing carbon emissions, because we still have to have those gas or coal plants.

Gillespie: This is all kind of pursuant to the idea that climate change is happening, and that it makes sense for the planet to reduce carbon emissions. In your reading of the data, what are the odds the bad scenario is going to happen?

Pinker: I couldn't assign a number to it. It strikes me as high enough that we should reduce the tail risk. There's a range of pretty gruesome scenarios as to how high sea levels could rise, and possible flips like the Gulf Stream being diverted that would turn Europe into Siberia. Not definitely going to happen, but high enough of a probability that the consumer should worry about it.

Gillespie: Your preferred fix to this is a carbon tax. How would that work?

Pinker: The idea would be to, as they say, internalize the externality of emitting the carbon that could result in climate change that harms everyone—but without the command-and-control mechanism where someone decides what source of energy we should use, what conservation methods we should adopt. The advantage of carbon pricing is that the decisions are distributed across billions of agents, who can weigh the various trade-offs—the benefit that you get from fossil fuels as opposed to the cost that the carbon tax would impose.

Gillespie: Political economy people worry about how to figure out the cost of a ton of carbon or exactly how much damage it does. How do you price it so that you don't create a false market that causes malinvestment?

Pinker: That risk can never be zero, because no one's omniscient, but I think having one is better than not having one.

Gillespie: Some people hate modernity because of environmental concerns, but it seems that the anti-Enlightenment attitudes on the right come from a different place. Who are the major players there, and what's motivating them?

Pinker: Some of the concerns are religious—we shouldn't play God by extending human lifespans, or, conversely, we don't even have to worry about climate change because God wouldn't let any bad thing happen.

Part of it comes from something that's called theoconservatism—the idea that the Enlightenment roots of the American social order were a big mistake, that it just has led to relativism and homosexuality and pornography.

Gillespie: Women wearing pants?

Pinker: And worse, just decadence and degeneration, because the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is just too tepid for a morally robust society. So we need something, some sort of rock-solid principles, which immediately are provided by religion—particularly Catholicism. This is a movement that distrusts science for its Promethean usurping of power from the gods, especially when it merges with classical liberalism and other Enlightenment values.

Gillespie: It seems to me that there are two major legacies of the Enlightenment. One is scientific progress, or the idea that we can and should investigate all aspects of the natural world and the social world and get to understand them better. But that in a weird way leads to things like Darwinism and other forms of scientific determinism, where we know why things happen, and we know they're going to happen in pretty predictable ways, and that limits our autonomy. On the other hand, there is the political legacy of the Enlightenment, which is the idea that each of us should be able to run our lives more than we did in the past, because we're all thinking agents who deserve life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Is there a tension between those two legacies? Because life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness means we have an open society, and an open society means we sometimes come across scientific discoveries that tell us we're not that special. You're never going to be a baseball player, I'm never going to be a Harvard professor. How do we maintain equality in the political sphere as science tells us we're more and more unequal?

Pinker: We have to embrace the ideal of equality of opportunity and equality of treatment under the law, as opposed to equality of outcome. That's an inescapable consequence of the fact that we're not clones. We're genetically different. But if you adopt a principle that we're not going to prejudge an individual by the characteristics of his or her group, that's a moral and political decision that is justifiable, and it's one that we can stick to.

Gillespie: Talk about the structural postmodern critique of the Enlightenment.

Pinker: It didn't take long after the Enlightenment for there to be a counter-Enlightenment movement. The 19th century Romantics, the cultural pessimists like [Arthur] Schopenhauer and [Friedrich] Nietzsche, lead to the Frankfurt School of [Max] Horkheimer and [Theodor] Adorno, and to the existentialists and then to the postmodernists, who rejected pretty much every one of the Enlightenment ideals. [They thought] reason was just a pretext to exert power, and the individual was a myth—individuals are embedded in a culture and it's the culture that's real.

One strain of that led to blood-in-the-soil nationalism. We're just sort of cells of a superorganism. There's no such thing as objective truth, just competing narratives, and far from there being progress, there has been deterioration, and any moment now the entire society will collapse.

Gillespie: Are there critiques of the Enlightenment that you find convincing? Because you kind of push away the negative things. I'm thinking of Adorno and Horkheimer saying the Enlightenment is totalitarian, because it controls every aspect of the human experience, much like Nazism or Stalinism or Maoism. You say, 'No, those were perversions of the Enlightenment.'

Pinker: Yeah, there is the danger of the 'No True Scotsman' fallacy. But no, Nazism was not an Enlightenment movement. I don't think you can trace it back to Adam Smith and David Hume and [Baruch] Spinoza and James Madison. It was counter-Enlightenment in valorizing the tribe over the individual, and it was opposed to liberal movements of the 19th century that tried to generate wealth, reduce injustices, maximize flourishing of as many people as possible. These were all anathema to the Nazis.

Gillespie: Isn't there a hubris that's part of the Enlightenment legacy that we always need to be on guard against?

Pinker: Yeah, and the Enlightenment had many contradictory strains, so it's in the very nature of the Enlightenment that it wasn't a doctrine or a catechism of beliefs. It would be impossible to say everything about the Enlightenment is worthy, because they disagreed with each other. There also was a critique of the Enlightenment from Edmund Burke, that we're just not smart enough to design a society from rational principles, so we should respect tradition and [existing] social structures even if we can't explain their rationale, because they keep us from teetering over the brink.

Gillespie: His great example of that was the French Revolution, which leveled all sorts of past institutions.

Pinker: Here's the way I would put it, though: Yeah, the Enlightenment as a movement, obviously, was filled with flaws. Because they're just guys. They couldn't have gotten everything right on the first try. They disagreed with each other, and there was a lot of stuff they didn't know. They didn't know evolution, they didn't know thermodynamics. It's really the ideals that I associate with the Enlightenment that we ought to venerate.

Gillespie: You say in the book that politicization makes us dumb. What's your general argument?

Pinker: People identify with what you might call tribes, and leftism and rightism have become tribes. We'll evaluate any idea in terms of how well it conforms with a particular set of ideas that happen to be associated with that tribe. We'll resist evidence to the contrary. We'll demonize those who disagree with us.

There are studies that show that people, when evaluating data from a hypothetical experiment—if it's politically neutral, like the efficacy of a skin cream—do a decent job of interpreting the numbers. But as soon as it's a political hot button, like concealed weapon laws, then they'll systematically misread the data in the direction that favors the position associated with their coalition.

Gillespie: What are the ways around that?

Pinker: Ideally, it would be reminding people that this phenomenon exists—that political tribalism makes us make math errors, that it is a human failing, and that we should evaluate policies in terms of evidence about their effects and how well they conform with what we want.

That is the idealization, but of course if we were rational enough to accept that, we probably wouldn't have fallen into tribalism in the first place. [Another solution], with perhaps more of an appeal to our emotional selves, would be to find spokespeople who are branded with the opposite coalition to speak in favor of a particular position. In the case of climate change, it would be far more effective if there were people on the libertarian right who were chosen as spokesmen, as opposed to Al Gore, who was the Democratic candidate for president, to frame issues in a way that doesn't immediately trigger your tribal affiliations.

We do know that issues can flip. Environmentalism used to be thought of as a right-wing position, because these were gentlemen in their country estates who valued the view and duck hunters who wanted the habitat preserved for their prey. Whereas serious progressives cared about real issues—

Gillespie: They want to put dams everywhere so that they could provide energy for poor people.

Pinker: Exactly.

Gillespie: You chastise the libertarian right for embracing a rigid dogma over serious introspection on things. Like, libertarians will go right from a regulation getting introduced to 'We're at the final terminus of the road to serfdom.'

Pinker: The next thing you know we're Venezuela, yeah.

Gillespie: Then there's the way politics damages academia. What are the worst elements or outgrowths of this kind of politicization as it affects you on a daily basis?

Pinker: There are some hypotheses that are hard to advance without being branded as a this-ist or a that-ist. The fact that men and women aren't indistinguishable, the fact that intelligence is in good part heritable, the fact that parenting doesn't have a lasting effect on the personalities of children, the fact that rates of crime differ across ethnic groups, the fact that policing has a large effect on the crime rate. I could go on.

Gillespie: The problem is that because of the politics around these issues, you're not even supposed to investigate them.

Pinker: I think there are two problems. One is simply that we can't converge on a most likely hypothesis if there are some hypotheses that are just undiscussable. It's only in the crucible of ideas and debate that you can converge on the truth.

The other is that, by making certain hypotheses undiscussable, you open a niche for people who stumble across them outside of the sandbox of academia. And they can often attach themselves to the most extreme versions, since they feel empowered that they've discovered a truth that's undiscussable in academia.

You get communities in the alt-right that often embrace quite illiberal, extreme views, because they feel so exhilarated that they've come across them. A silly example would be Milo Yiannopoulos saying that because women place a greater emphasis on family vs. career in their lifestyle trade-offs, we should keep women out of medical school, because they're just going to drop out and have babies.

It is actually a fact that there is a difference in the distribution of life priorities between men and women. Of course, that doesn't mean that all men place 100 percent weight on their career and 0 percent on family, or vice versa. And there are moral and political arguments why, even if it were the case that more women drop out, we would not want to keep them out of medical school. But that debate doesn't even take place if you can't acknowledge the fact that men and women have different distributions.

Gillespie: But in the university, it's not the Milo Yiannopouloses of the world that are keeping that conversation from happening.

Pinker: That's right, yes, but then these views can kind of fester in these online communities. Likewise, another example that I've given is that you can't really understand crime in this country without noting that there are pretty severe differences in rates of incidence across different ethnic groups and races. But if that's undiscussable and then you stumble across it because you go to FBI.gov, you might think, 'Oh, it shows that African Americans are inherently more violent.' Which of course is nonsense, because rates of crime [aren't static]. At other points in American history, it was the Irish-Americans who had the high rates of violent crime. So actually, by suppressing a basic statistical fact, it can encourage racism in these alternative communities, because they never get pushback in an arena in which all hypotheses are out there and their limitations can be rationally discussed.

Gillespie: I can remember in grad school in the late '80s and early '90s, I had a lot of professors who had gone to Berkeley in the '60s. I was libertarian and they didn't particularly agree with me about a lot of things, but they were interested in discussing them. That seems to have faded. Why is the university no longer the place where you argue all ideas and get rid of the ones that can't go more than a few rounds without being revealed as lightweight?

Pinker: I don't know the exact history, but there was a fair amount of intolerance in the '70s. It was not exactly a golden age for speech. A lot of speakers were, as we now say, deplatformed. But It does seem to have gotten worse in the last five to 10 years, and I don't know if it's that the Baby Boom generation itself had some intolerance toward non-leftist views, then became the establishment and established norms that the millennial generation has internalized.

Gillespie: Is it coming more from the faculty or the students?

Pinker: I think a lot of it actually comes from the student life bureaucracy, the various deans and associate deans and Title IX administrators and affirmative action administrators. They have formed this new guild that operates outside the ordinary university chain of command, with a president and a provost who rose from the faculty and presumably have some commitment to intellectual values. This is an autonomous culture that moves laterally from university to university. They have their own norms, and the control of a lot of student life has kind of been outsourced to them.

Gillespie: You make a case for studying the humanities as well as hard sciences. Yet you're also extremely critical of what's happening in the humanities.

Pinker: Well, if the humanities are defined as the study of, say, products of the human mind—of symbolic creations including art, ideas, political philosophies, and so on—there shouldn't be a debate between the sciences and the humanities. We've obviously got to nurture scholarship of artists and writers and thinkers, past and present, and that has to be reinterpreted every generation with new understanding both of sources and of the greater intellectual context.

It's just this particular set of assumptions that happens to have taken over big sectors of the humanities that I think is a source of the problem. Obscurantism in expression—the fact that by far the most turgid, jargon-ridden prose comes out of the postmodernist humanities—the deep hatred of the institutions of modernity, the equation of liberal democracy with fascism, the feeling that society is in an ever-worsening spiral of decline, and the lack of appreciation, I think, that the institutions of liberal democracy have made the humanities possible, made them flourish. It's that cluster of ideas, which is not the same as the humanities, but just happens to have descended over large sectors of the academic humanities.

Gillespie: You're making a defense of the Enlightenment. Are you optimistic that your intervention here will help?

Pinker: The honest answer is I don't know. I think it would be grandiose to say that my book will change the situation. I'm doing what I can. The optimism that I'm associated with in this book isn't just thinking that everything is bound to get better—that there's some law of nature that will carry everything ever upward. It's really more an empirical defense of progress. We have made accomplishments. They're precious, we're always in danger of losing them, and what will happen going forward depends very much on the choices that we make now.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Another possible contributor was the historic memory of the wars of religion. That showed that dogmas about faith and scripture and interpretation and messiahs and so on could lead to tremendous carnage, and people thought, 'Let's not do that again.'

This is a topic I'm very interested in. For we have seen many religious wars in history that were atrocities, just as you said. But I wonder how much of it is really religion and how much is just that the church was the major international institution in those days, and thus it carries the blame.

Or to put it another way, how much of it is just an inherent warlike tendency of man, and how much of it is any particular institution.

A lot of it. To say that religious wars are all about religion and not about other things that religion is used as a rationalization for is to be pretty historically ignorant. I have no idea who Pinker is, but he seems to have nothing interesting or particularly enlightening to say.

I'd give him another chance. I find that he has quite a lot that is interesting to say about his actual subjects of expertise, which are psychology and linguistics.

^^^ This guy gets it.

R???eal google job

Bryce . although Chris `s remark is nice, previous day I got a great new Chevrolet after having made $9508 this-past/month and would you believe, ten k this past-month . with-out any doubt it's my job Iover had . I began this four months/ago and almost immediately made myself over $69 per-hour.look here more

http://www.richdeck.com

Which is like applying physics, neuroscience, and physiology as to why a perfect three point set up by LeBraun James is just awesome.

I am trying to teach the new puppy about catching the tennis ball in the air. He will eventually understand.

The joy of catching the ball is not about Newtonian equations although those are fun.

So I agree with you. He is missing the point. The joy of living and all the crap we deal with is the point.

Pinker is a pseudo-scientist and a huckster.

I tend to agree with you.

You just said you have no idea who he is.

He does now.

That's not what Pinker said at all. He said that religious dogma led to tremendous carnage in the form of the [European] wars of religion, which are a specific series of wars. The dogma relevant to the Enlightenment philosophers from 1552 AD to 1700 AD was religious dogma and the animosity between Protestants, Anabaptists, and Catholics was primarily along religious lines. Most European wars of this time had religious dogma as an element. However, Pinker does not believe that these wars were only due to religion; you're just reading into it extremely uncharitably. Politics certainly played a role.

In fact, everything that he said is empirically true. Religious dogma did lead to an extremely protracted series of conflicts (in addition to other factors) and then once the Enlightenment was in full swing wars waged over religious conflicts in Enlightenment Europe virtually ceased, although it certainly played a factor in the normal (but fewer) wars.

If it makes you feel better, I am sure that Pinker blames all forms of totalitarian dogma and not just Renaissance Christian doctrines for terrible wars.

Politics was a major role. France allied with the Protestants against other Catholics because they didn't want a German and Spanish dominated Europe.

Pinker is grossly ignorant of history. The idea of equality and equal rights is directly informed by Christianity, NOT the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment stole it from Christians. Humanists have been parading around in this Christian skin ever since, pretending they owned it.

Just one example: Galatians 3:28 "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus." There are DOZENS more quotes demonstrating the same principle here. Google search "all are equal in christ jesus" and click the second link, openbible.info

The comments about the wars of religion are equally ignorant.

Read the Great Big Book of Horrible Things, probably the definitive work on human atrocities. Of the top 25 body-bag producing events in recorded history, only FOUR can credibly be attributed to religion.

The wars of SCIENCE have created hecatombs of bodies. WW II leads the list. It was eugenic race theory in action. The Germans considered Jews and Slavs racially inferior,

The Japanese considered Chinese, Koreans and southeast Asians racially inferior

The Americans considered Japanese racially inferior.

And what about atheistic communism, part of the science of economics?

Religion is nowhere near effective at mass murder as humanism and science is.

There is some truth in what you say just as there is some falsehood due to the extremes you take your argument. One way or the other, however, it does not matter much whether science or religion can take credit for more bodies because it was still the same humans performing the actions. We are the common denominator.

You missed the point. The Enlightenment philosophers criticized religious dogma because it was the biggest factor they saw in the preceding wars. They didn't have access to the political reasons that we can see now, and they still criticized what would become nationalism for contributing to war. I am 100% sure that if they saw the trauma non-religious dogma would inflict in the future that they would reject it as well.

I want to also point out that Galatians 3:28 is directed at Christians and does not include non-Christians. It was really just a way to get Christians to stop fighting each other, which was really the whole point of Galatians. And for all of this supposed equality, life was certainly stratified unequally until we were well within the Enlightenment.

Religious dogma did lead to an extremely protracted series of conflicts

No it didn't. It was used as a way back then to mobilize populations in exactly the same way as posters of Germans bayoneting babies was used in WW2 - or epithets/rhetoric (eg dominoes will fall, commies are everywhere, etc) are used to fearmonger now.

Blaming the dogma is just a way of excusing the fearmongerer and the establishment.

The same could be said of John...

I think this is a laughably bad example. I'll cite both WW1 & WW2 as examples of why people didn't actually come to the conclusion of 'Let's not do that again.'.

Rather than looking at those wars as separate unrelated incidents, look at them as two parts of a single longer conflict. Then consider what has followed.

Although, I do think the impulse remains. Just that, in modern times, the totalitarian 'isms' has filled the niche formerly held by diety based religions.

"Just that, in modern times, the totalitarian 'isms' has filled the niche formerly held by diety based religions."

Yes, agreed.

Blasphemy!

If you want to know what someone really worships ask them what you cannot riducule.

The truth.

I am into anti-ismizationism!

But then again, my other "ism" is GovernmentAlmightyism...

Scienfoology Song? GAWD = Government Almighty's Wrath Delivers

Government loves me, This I know,

For the Government tells me so,

Little ones to GAWD belong,

We are weak, but GAWD is strong!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

My Nannies tell me so!

GAWD does love me, yes indeed,

Keeps me safe, and gives me feed,

Shelters me from bad drugs and weed,

And gives me all that I might need!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

My Nannies tell me so!

DEA, CIA, KGB,

Our protectors, they will be,

FBI, TSA, and FDA,

With us, astride us, in every way!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

Yes, Guv-Mint loves me!

My Nannies tell me so!

Organized religion is just a particular form of tribalism. It doesn't matter whether it is Protestants vs. Catholics, Serbs vs. Bosnians, or Jacobins vs. the aristocrats. People will dehumanize and attack the Other, because most people have not self-actualized enough to overcome our biological heritage of pack mentality. Why do wolves kill the pups of a competing pack?

It can be a form of tribalism but it doesn't have to be any more than any other set of beliefs does.

Which makes sense when you consider that Marxism - international socialism was a direct reaction to the international/universal appeal (appeal, not as "attractiveness," appeal as "offer") of classical liberalism.

A lot of the appeal of Marxism lies in its offer of being part of an elite that was helping to bring the world into a better state. Moreover, the heart of Marxism is the collective guilt based on economic class, which is nothing but tribalism. Socialism is nothing but tribalism. Tribalism says that your fortunes and misfortunes belong to the tribe. if you fail, the tribe will take care of you. If you succeed, the benefits of that go to the tribe. Socialism is the exact same thing with fancy rationalizations.

I guess I wasn't clear.

One of the central tenets of classical liberalism, one of it's novel ones, is it's universality. Part of the point of the exercise was to escape tribalisms. This was not accidental in any way.

Yes socialism tends towards tribalism which is not exactly surprising since tribalism is always based upon some social group. Which is exactly why Marx posited something universal - ie international socialism. He had to. At that point in time, a world where there already was a "way out" of tribalism anythign that didn't at least promise it's own solution was going nowhere fast.

Marx wanted to keep his collective, and that was the only way to square the circle.

"Moreover, the heart of Marxism is the collective guilt based on economic class, which is nothing but tribalism."

I am not sure you can charge the impoverished Prussian serf or the upper England coal miner as possessing of class guilt. Perhaps the bourgeois intellectual leadership, but not the worker bees.

And honestly to both you guys I think you are underplaying the class conflicts in Europe during the 1800s. I would not exactly be enthralled with the state of the world if I was born into peasant stock and had to watch nobles and aristocrats parade around with land, titles, and deeds simply because the were born into aristocratic stock. It would probably make me pretty annoyed and maybe even turn me Marxist if they were the only people offering me a solution (whether political triumph or bullets) to my aristocrat problem.

I don't think I'm underplaying it. The same issues existed in the 1700's as well. However the responses that were generated in each century - the French Enlightenement and what it begat vs. the Scottish Enlightenment and what it begat couldn't be more telling.

Saying that the Marxists were the only people offering a solution is grossly overplaying someone's hand.

If I'm underplaying anything it is the abject horrors that were unleashed upon the world by Rousseau and his ilk.

"...Rousseau and his ilk"????

Are you trying to MILK Rousseau and his ilk!??!?

I'm not into milking the ilk, no matter WHOSE ilk it is that you milk!!!

(Now elk-milk is a totally DIFFERENT matter).

People will dehumanize and attack the Other, because most people have not self-actualized enough to overcome our biological heritage of pack mentality. Why do wolves kill the pups of a competing pack?

The self-actualized people aren't actually any more 'self-actualized' and, instead just erecting new religions and tribes.

Read the implications of Dunbar, you can't just will yourself into greater computing power and adaptability to nuance any more than you can will enemies, detractors, and competitors out of existence.

Ants have something like 250K neurons, less than 1,000th of 1% of the neurons in the human brain and they still manage to drum up the behavioral equality of 'other' and 'tribe'. You'd have to annihilate nearly all life on Earth to fully divest or transcend away from tribalism.

"You'd have to annihilate nearly all life on Earth to fully divest or transcend away from tribalism."

Der TrumpfenFuhrer will lead the way in this matter!!!!

Reason being the ideal that we analyze our predicament using reason as opposed to dogma, authority, charisma, intuition, mysticism. Science being the ideal that we seek to understand the world by formulating hypotheses and testing them against reality. Humanism, that we hold out the well-being of men, women and children and other sentient creatures as the highest good, as opposed to the glory of the tribe or the race or the nation, as opposed to religious doctrine. And progress, that if we apply sympathy and reason to making people better off, we can gradually succeed.

He sounds like an over-earnest 8th grader there. The idea that humans are the highest good and not the collective is dogma you fucking half wit. Just because it is your dogma doesn't mean it isn't dogma.

There is also that many attempts to apply extreme rationalization to human existence have ended up very bloody. The last two centuries plus has been a testament to that. Just because a movement calls its guiding light "reason" does not make it immune to the foibles of human nature and that it won't be just another bigoted tribe.

Gillespie to his credit brings up the French Revolution. And Pinker's response is almost comical

Gillespie: His great example of that was the French Revolution, which leveled all sorts of past institutions.

Pinker: Here's the way I would put it, though: Yeah, the Enlightenment as a movement, obviously, was filled with flaws. Because they're just guys. They couldn't have gotten everything right on the first try. They disagreed with each other, and there was a lot of stuff they didn't know. They didn't know evolution, they didn't know thermodynamics. It's really the ideals that I associate with the Enlightenment that we ought to venerate.

He sounds like a Marxist dismissing Stalin there. "Hey no everyone agrees and things just got out of hand". Well no shit. The fact that not everyone agrees and if you start setting up Gods, even if you name them nice names like "Science" and "reason" things do get out of hand. That is the whole point of bringing up the French Revolution.

I am not sure how knowledge of thermodynamics and evolution would have prevented how the French Revolution went wrong. It seems a category error.

I just finished a video course on the French Revolution. It was irritating to what pains the lecturer was going to to say that the Jacobins were on the right track but they went a bit off yhe rails with the Terror because they were under so pressure from Austria and Prussia and the counterrevolts that were springing up.

One of the Revolutions grand ideas at rationaluzing life was implementing a ten day week. Of course, that meant you only got a day off every tenth day rather than every seventh. They seemed confused that many people were not hsppy with that.

"what pains the lecturer was going to to say that the Jacobins were on the right track but they went a bit off yhe rails with the Terror because they were under so pressure from Austria and Prussia and the counterrevolts that were springing up."

But with all the unrest and Johnson in the White House, I just got so stressed, baby!

(I could look up the exact quote but that would be trying too hard)

Is he a bit extreme? Yes. But ultimately he is right, we need to hold onto the things that actually made America great. Opportunity, hardwork, equality. That comes hand in hand with celebrating the people and ideas that guided the Enlightenment, especially the British branch of the Enlightenment. If we crap on something just because it is not "perfect" then you are being unrealistic.

Yes, we should be celebrating the Enlightenment just as long as we never treat the ideas and ways of thinking discovered then as an orthodoxy but as the first step on the road towards greater understanding of ourselves and the world we live in. Brits like John Locke were a practical people, we should continue to hold onto those kinds of ethics.

You want enlightenment?

Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.

Nothing in there about nuclear power, global climate warming changes, or regulations.

That's gonna leave a mark.

Actually no, I've had all the enlightenment I can stand, thankyouverymuch.

What I'd actually like is a horde of crazed barbarians lopping off enlightened heads.

Do not unto others what you would not have others do unto you.

wtf??? I will not pollute the air you breathe as I would hope you would not pollute the air I breathe. And if we both cannot agree organically to not pollute the air we breathe, then we need ... regulations. Clearly Pinker is correct about the Libertarian insanity of equating every common-sense regulation with a descent into Venezuela.

Do unto others: I include putting the shit you use for farming into the river flowing downstream that people drink into the category of doing unto others something that you wouldn't want done to yourself. How do you prevent people from doing that without regulation? They are free to put the shit into the river because it's on their property. Isn't there something about the commons that requires regulation to some extent. Similar issue for air pollution and the factory that you own.

Yeah, so we can't credit the Enlightenment for that, because it was part of the transition to modernity. But it got a boost in the 19th century with the formation of professional police forces and with the more systematic application of criminal justice, and then in the 1990s and the 21st century with data-driven policing.

The world extends beyond Europe. I love the Enlightenment as much as anyone. But lots of pre-enlightenment or even anti-enlightenment societies had very low crime rates. And some countries today have enormously bad crime rates. Data-driven police policy? Wow, if only places like Mexico or El Salvador knew that the solution to their problems is data-driven police policy. Wow.

You're a fucking idiot blowhard lol. How about you read the damn book before you prattle on like a reactionary retard?

"Pope Francis is part of the problem, nuclear energy is part of the solution, and libertarians need to admit that not every regulation will turn us into Venezuela."

Two out of three ain't bad.

He'd be a hall of famer in MLB.

Maybe, exccept Pope Francis may more represent Peronista ideology more than good Catholic theology.

The problem with guys like this is that if "reason" and "science' are so infallible, then why have any respect for freedom except when reason and science tell you that you should? The idea that we can use reason and science to find answers to value questions like what is the good is just as romantic as fascism. And the belief that reason and science are somehow infallible and should always guide our actions is just as Utopian as any form of Marxism.

That idea forms a large part of the foundation of Marxism. Marxism styled itself as a scientific ideology.

That does not it is entirely without merit, but it is easy to become arrogant and authoritarian when people disagree with your ideas.

Yes. Every form of Utopianism cloaks itself in reason and claims to be science. The Fascists did it too. So claiming, just follow reason and science is no more enlightening than saying "just follow your heart."

"" if "reason" and "science' are so infallible, ""

This isn't what he argues.

Okay, then what does he argue? If he doesn't, then what is his point? That reason and science are great unless they are not? No shit.

[gets popcorn]

Don't get your hopes up. Gilmore will run away or launch some invective and name calling and various harrumphing about how obvious his point is and how stupid I must be to question it if he stays. I doubt he has the sack for an actual discussion.

You're making the "is" vs. "ought" fallacy.

Reason + science doesn't tell you what you ought to do; it tells you what is. It informs value-laden arguments, it doesn't replace them.

Its the same zero-sum complaint that everyone makes about pinker, mostly because no one actual responds to his arguments: they respond to what they *imagine* his argument is.

e.g. Pinker himself:

You're free to try and use the product of rational inquiry and scientific analysis to whatever value-laden end you want; what you're not free to do is misconstrue or misrepresent scientific results themselves.

e.g. pinker makes lots of evidence-based argument that "the world is getting better"

idiot in New Republic goes, "Uh, NUH UH" but doesn't even bother addressing Pinker's data or arguments.

basically, the latter guy handwaves the facts away as irrelevant. This is the sort of mindset Pinker's book is trying to undermine.

And again, no shit. And that would all be fine and good if he then didn't turn around and claim religion and mysticism and all the rest are so bad. How make these value judgments without such things? You can't. Or you can try, but then you are right back to using science and reason as some kind of infallible Gods.

he doesn't actually make this argument either

in fact he suggests specific benefits that both offer

Then he is saying nothing, other than wouldn't it be nice if everyone were reasonable. Big fucking deal.

"Pinker thinks X"

"No he doesn't"

"Well then fuck him he has no point"

QED

Yes QED. Your argument is "Pinker doesn't say that". And my response is "what does he say". And then your response to that is always a null set. Sorry but "religion and mysticism is great in limited senses then it should be reason and science" is not a profound or even meaningful point. It is just a fucking platitude.

technically that's not "my argument", its simply observing that you're talking about something which pinker doesn't actually say.

1) i didn't say what you just quoted

2) that sentence doesn't even make any sense.

what i specifically said, (and which is my own bad-summary of pinker, not to be confused with his own work) was

"Reason + science doesn't tell you what you ought to do; it tells you what is. It informs value-laden arguments, it doesn't replace them."

i.e.. you can use 'religion and mysticism', or any non-scientific argument, to make appeals to Ethos or Pathos... but you can't really use them as a replacement for Logos.

in the example i gave above i pointed to a TNR article attempting to "rebut" pinker which effectively ignored the arguments pinker made (about improving human conditions around the world).

That was an example of the "anti-science" mindset, which pretends to be able to draw conclusions completely contrary to what basic data say; its anti-intellectual, irrational, and illiberal (and has nothing to do w/ 'religion' fwiw).

that's what he's talking about. not your contrived "anti god" strawman, or whatever it is.

"Reason + science doesn't tell you what you ought to do; it tells you what is. It informs value-laden arguments, it doesn't replace them."

If you can't understand how it is an assumption saying "reason and science tell you what is", I don't know what to do for you. To say that reason and science have value, you have to define what value is. And even if you do that, how much value it has and how much it should inform your decision making and when is the entire fucking debate that man has been having since he first became self aware. Pinker is saying nothing. He is just begging the question.

...../ )

.....' /

---' (_____

......... ((__)

..... _ ((___)

....... -'((__)

--.___((_)

"what pinker says is stupid"

"what did he say"

"he says you should have evidence for your beliefs"

"wow. that doesn't sound too crazy. how are you so sure his argument is stupid"

"i can just tell from this blog i read."

"so you never actually read anything he wrote"

"no, fuck that guy, why bother? its stupid"

"wow, you totally pwned him"

And that would all be fine and good if he then didn't turn around and claim religion and mysticism and all the rest are so bad. How make these value judgments without such things?

Are you actually asking why people shouldn't base their moral framework on a belief in magic and imaginary beings?

They have to base it on something. Everyone starts somewhere and it is all faith-based. You want to base your morals on reason? Okay, reason based on what principles? You can't use reason to justify its own assumptions. So where do your assumptions come from? They come from two places religion or preference. Unless you want to buy into total nihilism, which no sane human in history I know of ever has had the courage to do, then you are basing your morality on faith and imagination. That is all it is. You are no less of theist than the biggest holy roller. You just call your God "natural rights" or "reason" or "science" or whatever else you choose.

[drives to the store to buy more popcorn]

They have to base it on something. Everyone starts somewhere and it is all faith-based.

Well, you can start with axioms or assumptions, but that doesn't make the starting point faith-based. It's definitely not based on faith in spirits and magic, anyway.

You want to base your morals on reason? Okay, reason based on what principles?

You can, if you so choose, base your ethical framework on how you would like to be treated by others, ie The Golden Rule. When everyone treats each other the way they would like to be treated, then over time this will average out into a common set of morals and customs in the society in question. No gods needed. If you don't follow the general morals of the society, the members of that society will likely punish you or do what they can to make you stop violating "the rules." If you must believe that a god and not mere man will punish you for not following The Golden Rule, then go ahead and believe it. Most religions have some form of it in their books anyway.

Well, you can start with axioms or assumptions, but that doesn't make the starting point faith-based. It's definitely not based on faith in spirits and magic, anyway.

Yes it does. You can't use reason to justify its underlying assumptions. Reason tells you the logical consequences of the assumptions but it can't justify them. So it is an act of faith. You are assuming the assumptions are true. You have to. If you didn't, then there would be nothing to reason from. And you can't prove them using reason. You have to have first principles or you can't reason. And those principles can't be reasoned. That has been known since Aristotle.

You can, if you so choose, base your ethical framework on how you would like to be treated by others, ie The Golden Rule.

Sure you can. But who says that is best? You like that, but I don't'. I have a different set of assumptions that tell me to treat people differently. Our two systems of ethics are totally incompatible and separate from each other. There is no way to establish one's primacy over the other. It is just a question of taste or faith.

" you can start with axioms or assumptions"

You are just euphemising.

In any sort of reductive argument you will always reach the metaphysical argument of "that's just the way it is."

That you prefer to term them 'axioms' or 'assumptions' does not, in any meaningful way, distinguish them from 'magic' or 'imaginary beings.'

You just think that makes them sound better.

That you prefer to term them 'axioms' or 'assumptions' does not, in any meaningful way, distinguish them from 'magic' or 'imaginary beings.'

Axioms and assumptions are falsifiable. In science, one can observe or create an experiment to potentially falsify any scientific theory, statement, or hypotheses. Science regularly discards any theory/statement/hypotheses that is observed to be untrue. If no experiment can be crafted that could falsify a statement/theory/hypotheses then it is not scientific.

We cannot create an experiment that would falsify God. You have to take God on faith.

Unless you want to buy into total nihilism, which no sane human in history I know of ever has had the courage to do, then you are basing your morality on faith and imagination.

Wait, really? I guess my eyes moved past this part too quickly.

What do you mean by "total nihilism"? The realization that no part of existence has any purpose or higher meaning? And realizing this takes courage? Well, call me Harriet Tubman because that's the case. Life has no purpose or meaning beyond what you want to give it. Sorry to break the news to you.

Total Nihilism is believing in absolute moral relativity. It is believing that nothing is true or not true and no way to judge anything or make sense of anything.

Total Nihilism is believing in absolute moral relativity. It is believing that nothing is true or not true and no way to judge anything or make sense of anything.

Uh, ok. There is very likely some immutable underlying reality to everything (maybe). If so, then some set of facts out there must be correct (or "true"), but not for human interaction. There is simply no single perfect moral framework. Of course there is always a way to judge things and make sense of them for yourself, but to say that your preferred way is "the" one correct way to do so when it comes to human interaction is ridiculous. I have a preferred moral framework, but there's no way I can claim that it's absolutely the "correct" moral framework because there's no such thing. It's just the one that I think is best. If you think your preferred way is the one way because your god said so, that's just delusional.

Nihilism is related to, but does not necessarily include, moral relativity. Moral relativity suggests that morality has some dependence on the individual and nihilism suggests that morality does not exist objectively, and therefore has no dependence on the individual. Besides, moral relativism does not actually require one to not judge another's morality; that's only a facet of post-1950s postmodernism.

Besides, moral relativity != relativity of truth. Nihilism is foremost about rejecting the idea morality is real and that reality has inherent meaning, not about rejecting all of reality.

So where do your assumptions come from? They come from two places religion or preference. Unless you want to buy into total nihilism

If all morals are preferences they're all equally valid. This is really just a dressed up way of dodging the fact that someone is a moral relativist. And moral relativism is just a dressed up way of dodging the fact that someone is a moral nihilist.

If all morals are preferences they're all equally valid.

They are all indeed equally "valid" if you attempt to compare them to some absolute standard because there is no such standard, but there are moral frameworks that are more "viable" than others.

If a person's morality can be summed up as "all those who oppose my will must die," it's most likely not a very viable morality. The only thing holding him back is the will and ability of others, but large numbers of people will not abide it. Usually people with this sort of morality don't make it very far, so it's not very viable one.

Of course, you're basically ceding the ground that there's nothing wrong with this idea inherently. Heck, you've now ceded that there is nothing wrong with murder. Or with the Evangelicals suppressing the gayz. It's all a question of whether or not it can be implemented, right? Locking the Japs up in WWII was easily implemented, so nothing wrong with that, right?

There is no objectively correct way to play football. That does not mean that I'm as good a player as Clay Matthews.

That's how most non-postmodern moral relativists work. In this view, there are no objective moral laws that you can somehow consult. You can still judge people based on a non-objective framework.

Or to play at your "gotcha" questions, you have to admit that you don't have access to the objective book of moral laws that moral objectivism allows for. How then, can you judge the Evangelicals right or wrong? How can murder be wrong? You have to abide by a separate, non-objective, framework (like religion) and hope that it aligns with the objective framework.

Of course, you're basically ceding the ground that there's nothing wrong with this idea inherently.

So? It's wrong according to me. I think it's wrong. Why? Because I have come to the conclusion, through reason, that if everyone had this same morality, my life would be in constant danger, and dammit, my survival instinct is pretty strong.

Or with the Evangelicals suppressing the gayz.

I personally think it's wrong because I have come to the conclusion, through reason, that if everyone had this same morality, my personal freedom would be in constant danger, and dammit, my instinct to do as I like is pretty strong.

It's all a question of whether or not it can be implemented, right? Locking the Japs up in WWII was easily implemented, so nothing wrong with that, right?

Ultimately, everything is a question of whether or not it can be implemented or not. But whether it's right or wrong is up to you. I personally think it's wrong because I have come to the conclusion, through reason, that if everyone locked up people they were afraid of, my personal freedom would be in constant danger, and dammit, my desire to not be locked in a prison camp is pretty strong.

So if you need a non-religious starting point for a moral framework, then it's your survival instinct. It makes you think things like "I deserve to live" which is another way to say "I have a right to life." You can then go where that takes you.

Kivlor, there is no big rule book in the sky that to tell you that any particular morality is objectively right or wrong. I don't understand why you can't understand this.

Juice, I do understand what you are saying. And I haven't disagreed with that statement. What I have disagreed with is the positions that there is no objective right and wrong / that all positions on right and wrong are merely preference. What I don't get is how you jump from that to "Therefore Kivlor's religion".

I personally think it's wrong because I have come to the conclusion, through reason, that if everyone had this same morality, my personal freedom would be in constant danger, and dammit, my instinct to do as I like is pretty strong.

This can be shortened and restated as: "Personally I think it's wrong because I've come to the conclusion that I have emotions and they are strong."

That's all it is. "I have emotions and they are strong. Therefore Policy." Isn't this exactly what libertarians usually mock knee-jerk cries for legislation over? Is morality like broccoli or carrots or beef or potatoes: to be eaten if you like it and to be not eaten if you don't?

I want Stephen Pinker's Hair. Now!

He's no James Altucher.

I want Stephen Pinker's hair so I can do something useful with it.

No! that's the whole point. *it cannot be contained*

"Gillespie: You talk about how there's a strong argument for nuclear energy if what you care about is how to get the most energy out of the fewest greenhouse gases. How did you come to appreciate nuclear?"

+1

Pinker is 100% correct, not every regulation turns us into Venezuela. That's obvious on its face, but speaking personally, it would sure be nice if certain segments of society would stop treating every lack of regulation as making us into Somalia.

Not every regulation turns us into Venezuela, but refusing to regulate doesn't turn us into Somalia! either.

He's slowly morphing into Albert Einstein.

Pinker mentions "data-driven policing" which "put the police where the crime was starting to grow before it could explode" is seen in some sectors as racist.

It also buys into the assumption that crime is caused by lack of policing instead of other forms of societal breakdown. At heart, he is a technocrat. He dismisses religion and tradition and anything other than reason and science out of hand but then magically assumes that cops are going, to be honest, and laws justly and effectively administered because well everyone is just that reasonable.

It never seems to occur to him that maybe there is more to ethical behavior than reason. That perhaps things like religion and tradition serve to give people a reason to be ethical where reason alone fails.

It also buys into the assumption that crime is caused by lack of policing instead of other forms of societal breakdown.

Yup.

That perhaps things like religion and tradition serve to give people a reason to be ethical where reason alone fails.

Is forcing a woman to cover her face in public ethical or unethical?

Depends on how you define ethical. Why do you think your ethics are universal? Maybe I want women to cover their face in public and by my ethics, it is required. Who are you to say I am wrong? You can say you don't like it. But so what? I don't like your ethics. You go to your church and I will go to mine.

It's for her own protection. So you figure it out.

You can reason yourself into justifying anything. You just have to start with the right assumptions. That is why it is called a rationalization.

You can reason yourself into justifying anything.

Just like you can religion yourself into justifying anything. But religion is the correct way to do it.

It is not the correct way, it is the only way. You have to start somewhere. If you want to call where you start "natural rights" or the "golden rule", good for you. But stop kidding yourself and thinking that isn't a simple form of theism and religion.

It is not the correct way, it is the only way. You have to start somewhere. If you want to call where you start "natural rights" or the "golden rule", good for you. But stop kidding yourself and thinking that isn't a simple form of theism and religion.

I never said The Golden Rule was some absolute standard of morality that exists outside of a human's mind. I simply said it's one way to have a moral framework without invoking the supernatural. And there's really no such thing as "natural rights" the way most people understand that term, but reciprocal behavior is a pretty natural thing for humans. You treated me well, so I'll treat you well. You treated me poorly, so I'll retaliate. It's just a thing that humans tend to do naturally.

I think some people with strong religious faith realize that it's a sort of mental crutch, so to make themselves feel better about it, they assume that those who have freed themselves from such crutches must be fooling themselves and they actually must have some form of religious faith, because you're unable to comprehend living without it.

There's also social evolution....i.e. people have evolved to form relationships and social structures that are beneficial to them. No need for a zero-state set of assumptions, religion or what have you.

I like his observations on pessimism vs optimism.

Ugh, Schopenhauer, that dude was a ray of sunshine.

I like the 19th Century Germans a lot. Those guys owned up to being atheists and were willing to see the consequences and it wasn't pretty.

19th century Germans were by and large a bunch of worhtless pieces of Romantic trash that helped to spawn Hitler, Stalin, postomodernism, and all other forms of irrationality.

We have on team A:

1) Marx and his buddy Hegel with their dialectic retardation

and on team B:

2) Rousseau (I know, French) who helped lead to Nietzsche and their worship of amoral power ubermensch

Who all helped continue the Continental romantic retardation that eventually were harnessed by totalitarians, postmodernism, and worst of all Derrida and Foucoult. I fucking DESPISE Derrida and Foucoult. Anytime any of my phony intellectual friends use the word dialectic in a sentence or deconstruction I want to about punch them in the face.

By and large the rationality of the Brits was the biggest saving grace of the Enlightenment, the Continentals were all too built up with Catholic guilt and repression to actually look at the world rationally and in a positive manner.

What? Nobody's ever said such a thing. Certainly not here.

It's a straw man, so of course it appeals to you.

I see John is throwing a tantrum because someone implied his sky grandpa might not be real.

Not really. You'd understand his point if you had a basic grasp of philosophy and logic.

I think that you can't grasp what it's like to be devoid of all religious faith. It's beyond your abilities.

And what exactly gives you this foolish notion?

All your comments.

You should try harder at reading then.

His point is that for some reason only a psychiatrist can explain he desperately needs to believe that some version of the fairy tale he was raised on is true.

"... implied his sky grandpa might not be real."

So you think everyone who practices a religion literally believes in a material deity/deities? Doesn't surprise me, the same 3rd grade religious thinking you assign to everyone is the same third grade political and philosophical thinking you display here day in day out with your usual hostility. I guess i would be bitter, angry and resentful too if I was a queer living in butt fuck oklahoma.

I don't give a fuck what form of magical fairy your stupid beliefs torture your rational mind into accepting as physical reality.

But John definitely believes in a literal grandpa in the sky.

Good one Tony. That must've been an example of that nuance you're always lecturing other posters on whenever they generalize one of your brilliant points. You may not worship magical faeries but you do comport yourself to the tenets of the faeries, which is sad. At least a nihilist, with any sense, would admit life is suffering and meaningless and snuff himself out, thereby being consistent. You, on the other hand, mime rationality and then go about your little rituals. Don't think for a second that the bullshit you spew out on a daily basis is any different from the dogmas repeated in those Gay Hatin' churches you fear so much.

WTF is faeries? Are you some kind of Canadian?

You should know, you are one, lol.

You know who else venerates the tribe over the individual?

Both major parties in the U. S.?

The Scottish part of the Enlightenment, as I understand it, was the part that influenced the American Founders. They went right out and called themselves the "common sense" school. That seems a bit more relaxed and non-silly than the French parts of the Enlightenment, which got a tad out of hand.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Reid

It was Thomas Paine who most famously promulgated the phrase 'common sense' over here. Although he wasn't exactly working from the same page as the Scotsmen. He went decidely off the rails himself, and almost lost his head during the French Revolution, only surviving thanks to some string pulling by James Monroe.

Excellent remark from Pinker @47:26. The basis of free speech.

I really like his theory on where the anti-enlightenment attitudes are coming from on college campuses. @52:40

It's something I haven't heard and it makes quite a bit of sense.

It's pretty much what I've always thought, but I think it's more that student affairs administrations more allow and amplify terrible students instead of driving it themselves. We got a bunch of questionably employable people, put them in jobs where suppressing internal unrest is of paramount importance, and then expanded their powers over several decades. Simple self-interest dictates that they'll quickly pander to tribalism and emotion, if only to galvanize their charges into one manageable "community." This all makes their job easier and even allows them to demand higher budgets and bigger departments. No political beliefs needed on their part.

I thought that you might like to know that you started 7/17 of the top-level threads on this article, by my count.

Anti-enlightenment attitudes are coming from college campuses because the Frankfurt School (ie. Cultural Marxism) is an expressed enemy of the individual rights enshrined within enlightenment principles.

None of it is accidental.