Making Malaria Mosquitoes Extinct Using Engineered Gene-Drives

"If my kids lived in Africa, I'd say, 'Go for it as quickly as possible,'" says researcher.

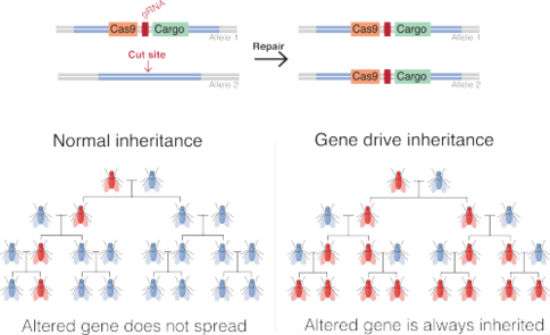

Roughly 212 million people are infected with mosquito-borne malaria parasites which kill about 429,000 of them each year. The main carrier of the parasite is the Anopheles gambiae species of mosquito. Researchers in Italy are using CRISPR genome editing to engineer a gene-drive that would make it impossible for females of that species to lay eggs. Males containing the gene-drive would be released to mate with females in the wild. Ordinarily, mosquito progeny get one copy of a gene from each parent, but in this case, the gene drive would excise and replace the natural copy from the wild parent with the version that prevents the females from laying their eggs. This guarantees that the engineered genes would get passed along when the next generation of mosquitoes breeds. Eventually, essentially all of the mosquitoes in the targeted species would carry the engineered version and the result would be a dramatically reduced number of disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Currently, the engineered mosquitoes are kept enclosed in laboratory cages that prevent their escape. The gene-drive research is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Target Malaria project. The technology would also work to control mosquito species that infect people with maladies like Zika virus and dengue fever.

Naturally, the usual suspect bioluddite activists oppose the development of this technology.

NPR's Morning Edition reports that Friends of the Earth (FOE) senior food and agriculture campaigner Dana Perls warns, "This is an experimental technology which could have devastating impacts." In addtion Nnimmo Bassey, director of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation in Nigeria tells NPR, "They're trying to use Africa as a big laboratory to test risky technologies. This is a technology where we don't know where it's going to end. We need to stop this right where it is."

FOE, along with numerous other anti-technology activist groups, are pushing a petition urging governments to impose "a global moratorium on any release of engineered gene drives. This moratorium is necessary to affirm the precautionary principle,* which is enshrined in international law, and to protect life on Earth as well as our food supply."

Contrary to this alarmism, MIT gene-drive research pioneer Kevin Esvelt points out that malaria infections are already imposing devastating effects on people. "If my kids lived in Africa, I'd say, 'Go for it as quickly as possible,'" he tells NPR. Esvelt himself has often warned scientists to move cautiously with the technology because it is so powerful. But Esvelt thinks Target Malaria has been acting responsibly.

"The known harm of malaria so outweighs the combined harms of everything that has been postulated could go wrong ecologically," Esvelt says.

The researchers in Italy believe that it will take at least another five years of research and consultation with local authorities before the engineered mosquitoes can be released from their cages into the wild. In the meantime, more than 2 million people will die while hundreds of millions must still endure the misery of malaria.

(*The precautionary principle is the idea that we should never do anything for the first time.)

Show Comments (37)