Meet the Good Soldier Švejk, Patron Saint of Malingerers and Saboteurs

A 1920s-era novel sheds light on Eastern European anti-authoritarianism.

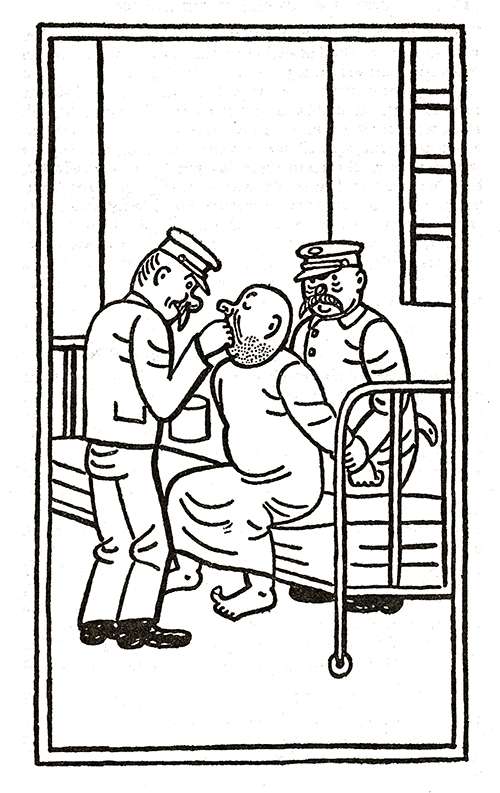

During the First World War, unenthusiastic enlistees would fake disability to avoid dying in a muddy trench. That's how the "war hero" of Jaroslav Hašek's classic novel The Good Soldier Švejk winds up in an army hospital a couple of chapters in. There, Švejk (pronounced Sh-vake) is joined by other Czech conscripts shamming illness or injury. The men are subjected to a sadistic regime of medicalized torture aimed at forcing them to admit their fakery and declare themselves fit for military service.

While recovering between "treatments," the malingerers, malcontents, and jailbirds of the Austro-Hungarian Empire ("the K & K," to borrow the era's German shorthand) compare notes on faking disability. One insists that insanity is the way to go, referring to his own phony religious mania. Another mentions a midwife who dislocates legs for the modest price of 20 crowns. A third says that he had his leg dislocated for a mere 10 crowns and three glasses of beer.

The bravest endure all five steps of the hospital's brutal treatment program, dying in a sick bed rather than admitting defeat and rejoining the regular army. Less stout-hearted soldiers, the narrator laments, give up after being threatened by the prospect of an enema with soapy water and glycerine.

In an alternate universe, The Good Soldier Švejk might have become a libertarian classic. (The novel was a favorite of rebel psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, who wrote to wide acclaim about how allegations of mental illness were used as an illegitimate excuse for oppression.) As it stands, the famous Czech satire is a hilarious and penetrating depiction of World War I's forgotten Eastern Front. It remains a touchstone today in Eastern Europe, with real-life statues commemorating the exploits of the protagonist in Poland and Ukraine. A Budapest-to-Prague rail line also bears Hašek's name, a tribute to his fictional avatar's long wartime detour into Hungary.

That character's long-lasting status as a folk hero says a lot about how much Eastern Europeans have come to reject the glamorization of war. The First World War inspired plenty of anti-war literature, but few books depict the average soldier's experience quite like Švejk. To Hašek, a former conscript himself, the conflict's real heroes were not the ones rushing off to die in the trenches.

Švejk also offers an intriguing look at how anti-authoritarian sentiments manifested themselves in the culture and politics of interwar Eastern Europe, a region that has rarely been favorable terrain for classical liberal ideas.

The Anti-Authoritarian Švejk

Švejk follows the titular character's misadventures across Eastern Europe during the opening months of the First World War. Glimpses of later anti-war satires appear on almost every page, from the comical incompetence of the creaking Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy to the over-the-top patriotism of Švejk's chief antagonist, the moronic Lieutenant Dub, to General Fink von Finkenstein, whose favorite hobby is court-martialing and hanging hapless subordinates.

Hašek never makes it entirely clear if Švejk is a complete boob or a canny everyman whose bumbling facade is a ploy to confound the officers of the tottering empire. Even through that ambiguity, the soldier's repeated encounters with the police, the mental health bureaucracy, and the army show a winning, corrosive contempt for large, impersonal institutions and for authority, be it clerical, bureaucratic, or military.

Švejk, which was first published in serialized form in the early 1920s, anticipates several other books in the past century's anti-authority canon. Joseph Heller says his Catch-22 was directly inspired by Hašek's work; the parallels between their protagonists' wartime experiences, a comical and occasionally terrifying mix of bureaucratic ineptitude and mass mobilization, are indeed apparent. Švejk's brief prewar detour in a mental asylum, meanwhile, is reminiscent of Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Hašek's portrayal of the Austro-Hungarian legal bureaucracy, which combines petty cruelty and total inscrutability in almost equal measure, is a humorous echo of his grimmer and more famous Czech contemporary, Franz Kafka.

To American readers, the dying days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire might seem unimaginably distant, a half-remembered figment from A.P. European History. But Švejk's plight and the timeless idiocy of his antagonists resonate across the ages. The good soldier and his comrades have been dragooned into the army of a ramshackle, multi-ethnic empire that inspires little in the way of loyalty or patriotism among its Czech subjects. These conscripts have only the dimmest understanding of their side's actual war aims, a condition, the book slyly suggests, shared by their clueless superiors.

The ruling Habsburg dynasty is foreign, as is its upper echelon of aristocrats and generals. Constant threats of draconian punishment keep the rank and file in line. The war itself is an endless series of drills, maneuvers, and marches toward a vaguely defined front. (Švejk never actually fires a shot.) Even the book's abrupt ending, a consequence of the author's untimely death, adds to the sense that the conflict will simply go on forever.

Although the novel's themes are deadly serious, its tone is unfailingly comic. This likely reflects the lived experience of the author, a wandering ne'er-do-well and itinerant journalist whose own capacity for troublemaking may have inspired his hero's more outrageous exploits. But the book's humor is also a product of Hašek's era.

It may sound absurd to say someone who lived through the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the First World War was lucky, especially considering Hašek's unhappy end (he died of alcoholism in 1923). Consider, though, the plight of his successors, fictional or otherwise. A latter-day Švejk would have witnessed the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Nazis, the industrial-scale horrors of World War II, and the Red Army's imposition at gunpoint of Soviet-style totalitarianism. It is difficult to imagine a character like Švejk surviving such circumstances, much less retaining his good-humored equanimity.

The book anticipates several other titles in the past century's anti-authority canon. Joseph Heller says Catch-22 was inspired by it, while Švejk's detour in a mental asylum is reminiscent of One Few Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

While Švejk's approach to most officers is antagonistic, obsequious, or slyly mocking, his relationship to his immediate superior, the put-upon Lieutenant Lukáš, is downright affectionate. And it is striking how often Švejk gets away with his mischief-making. In one scene, a secret policeman tries to get the as-yet-undrafted Švejk to confess his disloyal sentiments by feigning interest in Švejk's fraudulent canine-selling operation. The cop ends up eaten by the very dogs he purchases during the sting.

Švejk's encounters with the secret police and the military bureaucracy anticipate the horrors of Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism, yes, but the soft-edged absurdity of these episodes—even the eaten-by-dogs part reads as funny—seems almost quaint by comparison. Fortunately for Švejk, the machinery of social control had yet to be refined to its mid-century apex of cruelty and efficiency.

Still, through Švejk's unflappability and the book's humorous tone, a prescient and occasionally frightening look at the machinery of social control is legible. Toward the novel's start, a luckless innkeeper is arrested by the secret police for admitting he took down a portrait of the emperor because it was covered in fly shit. This, his unhappy wife later explains, was prima facie evidence of disloyalty to the dynasty.

The soft authoritarianism of the Habsburgs was certainly preferable to their Nazi and Soviet successors, but kernels of totalitarianism were already evident. And if the repeated and enthusiastic application of enemas to goad reluctant conscripts to the front seems over the top, consider that a similar technique was used by the Central Intelligence Agency in our own endless war on terror.

Burn-It-All-to-the-Ground Anarchism

While the novel's anti-war content and anti-authoritarian tone will ring sweetly to an American libertarian, Hašek was himself a left-wing anarchist, not a small-government liberal. His personal outlook was undoubtedly shaped by the political realities of Central Europe in the early 20th century, realities that help explain why that area of the world has not historically been receptive to libertarian ideas.

To a Czech whose political sympathies were anti-authoritarian and individualistic, the hereditary aristocracy, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, and even the Catholic Church must have seemed too imposing and entrenched to ever accommodate themselves to incremental reform. The empire's history of half-hearted liberalization, invariably followed by conservative backlash and retrenchment, is a case in point. And if classical liberalism could not find a home among the urbanized, anti-clerical, and commercially inclined Czechs, what hope did it have in less hospitable Eastern European environs? The ideological appeal of burn-it-all-to-the-ground anarchism can be at least partly attributed to the role of hereditary privilege in the region's troubled history. Western-style liberal reform just didn't seem an adequate solution to the severity of Eastern Europe's traditional authoritarianism.

In an American context, Hašek might have become a writer like H.L. Mencken, whose own libertarian outlook seemed inspired by the same streak of misanthropic individualism ("every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats"). But misanthropes, malcontents, and individualists in the United States have been fortunate in their circumstances. Libertarian ideas about freedom and opportunity are simply more plausible in a society without an entrenched (and highly visible) feudal elite whose political influence and economic privileges stymie dynamism and social mobility.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire and its troubled successor, Czechoslovakia, have vanished, but the spirit of Švejk lives on in Central and Eastern Europe. So too does a general suspicion of free markets. The Czech Republic's post-1989 shift from a centrally planned economy may have been guided by admirers of Margaret Thatcher, but the outcome was tainted by the old aristocracy's communist-era successors, who leveraged their privileged status to profit handsomely during the transition period. And the Czech Republic is one of the region's success stories.

Further to the east, in Romania, the entire economy is rumored to be dominated by former officers of the Securitate, the communist-era secret police force. As in Hašek's era, circumstances have conspired to limit the appeal of free markets.

But if libertarianism is in bad odor, a certain puckish anti-authoritarian feeling persists throughout the region. This is the everyman ideology of Švejk, whose political principles never extend further than annoying his superiors or finding his next meal, but who nonetheless embodies a certain bone-deep skepticism of grand schemes, martial fervor, and officious bureaucrats.

Squint closely enough, and you can see this anti-authoritarian streak in recent Czech history, from 1968's Prague Spring uprising to the rock 'n' roll underground of dissidents and intellectuals who helped usher their country out of the communist era. This spirit has even entered the Czech language, where "Švejking" (Švejkovina) has become shorthand for enduring (and occasionally subverting) the military bureaucracy.

Eastern Europe may never be hospitable terrain for libertarianism, but the continued resonance of Hašek's book is a hopeful indicator that, despite war, revolutionary upheaval, and generations of repression, a broad skepticism of authority in all its guises endures throughout the region. And one needn't be steeped in the history or culture of Eastern Europe to enjoy Švejk's escapades. Anyone who has dealt with officious bureaucrats, incompetent superiors, and tiresome rules will chuckle knowingly at the good soldier's misadventures, even as they see the absurd hell that militarized authoritarianism makes of human life.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Meet the Good Soldier Švejk, Patron Saint of Malingerers and Saboteurs."

Show Comments (16)