America Needs Immigrants Now More Than Ever

From falling birthrates to labor shortages, if you want to make America great again, the economic case for opening borders has never been stronger.

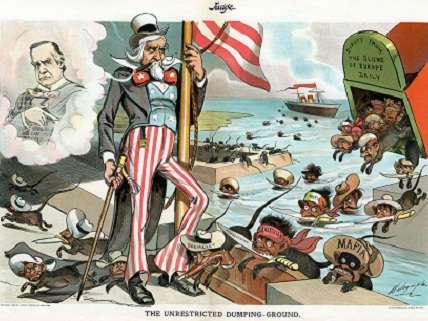

Immigration is the most-heated domestic policy topic today. Leave aside questions about whether members of MS-13, a violent gang started in Los Angeles, are "animals" or not and you still have Donald Trump dismissing migrants from "shithole countries", members of Congress such as Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa) railing against "somebody else's baby", and Republicans pushing to reduce legal immigration by 50 percent. Democrats these days are mostly welcoming to "dreamers" but we're just a few years removed from the policies of Barack Obama, who was arguably the "most anti-immigrant president since Eisenhower" and had no trouble deporting millions of Latinos and raiding workplaces suspected of employing undocumented workers.

Opponents of immigrants and immigration take their cues from President Trump, who opened his campaign for the Republican nomination by denouncing illegals entering from Mexico as nothing less than a criminal horde:

When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best. They're not sending you. They're not sending you. They're sending people that have lots of problems, and they're bringing those problems with us. They're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.

Opponents advance a host of other, sometimes contradictory arguments to make their case. Immigrants, they say, are lazy and soak up massive amounts of welfare even while they are willing to work harder and for less money than natives (a paradox known as "Schrodinger's Immigrant"). The litany also includes: Immigrants bring down wages, illegals make a joke of the rule of law, newcomers don't learn English, they vote Democratic, they destroy common culture, they are hotbeds of terrorism and crime, and on and on.

Supporters of current or expanded levels of immigration (I'm one) dutifully rebut all these arguments and more by pointing to relevant data, economic theory, and history. We also underscore American ideals of inclusion and a history of immigrant entrepreneurship, among other things.

Needless to say, the two sides rarely convince one another, or even come to a common understanding of what facts are true and relevant.

Which makes a column appearing in today's Wall Street Journal all the more interesting. Gerald F. Seib lays out a series of facts that I think everyone can agree on. They provide an excellent starting point for a different discussion about immigration, one that foregrounds the very sort of economic issues that both diehard Trump supporters and proponents of immigration can agree on. Among them:

- Unemployment is at 3.9 percent, the lowest it has been in 17 years.

- "There are 6.6 million job openings in the U.S., which means that, for the first time in history, there are enough openings to provide a job for every unemployed person in the country."

- Employers all over the country—Seib mentions Maryland crab processors, Alaskan fisheries, farmers in the heartland, and New Hampshire restaurants—"all say they are critically short of workers."

- The relatively few slots for annual H-1B and H-2B visas (for skilled and unskilled workers, respectively) have been filled at record paces this year already.

- "The [National Federation of Independent Business] says that 22% of small-business owners say finding qualified workers is their single most important business problem, more than those who cite taxes or regulations."

That's a portrait of an economy that is stuck in second gear, unable to expand to meet increasing demand and grow. Given the general listlessness of the American economy for virtually the entirety of the 21st century, in which annual economic growth has averaged under 2 percent (compared to about 3 percent from 1950 to 2000), we may not be immediately capable of recognizing the opportunity in front of us.

The long-term prospects for a healthy economy face real problems, reports Seib, including:

- "The fertility rate for women aged 15 to 44 was 60.2 births per 1,000 women, the lowest since the government began tracking that rate more than a century ago."

- Over the next three decades, the percentage of Americans over the age of 65 will become larger than the percentage under the age of 18, "a historic crossing of demographic lines."

Other sources underscore that immigration and births to immigrants, who tend to have more children than native-born women, are the only reasons why America's population is growing slightly. Unless it is supplemented by immigration, the decline in birth rates will disastrously sink the labor market in years to come. To get a sense of what happens when a country ages dramatically and doesn't replenish its population with younger residents, look to ultra-restrictionist Japan, which is the prime example of a First World "demographic disaster." Japan, which has fewer people than it did in 2000, is suffering a slow-motion economic collapse characterized by weak-to-nonexistent economic growth and an erosion of quality of life. As The Weekly Standard's Jonathan V. Last wrote in What to Expect When No One's Expecting: America's Coming Demographic Disaster, Japan's "continuously falling birthrates" has given rise to "a subculture that dresses dogs like babies and pushes them around in carriages, and a booming market in hyper-realistic-looking robot babies." No major developed country, he cautions, has managed to consistently grow economically with a shrinking population.

As a hardcore, principled libertarian, I'll defend anyone's right to dress dogs however they want and buy whatever sorts of robots the market can produce, but I don't think today's Japan is anybody's vision of making America great again.

The Journal's Seib concludes that "there is a good case that America's economy—growing and thriving—has never needed immigrant labor more than it does now." Yet the congressional reaction to the current situation is to crack down on illegal immigration, especially through intrusive employer sanctions. Hardliners are also calling for reductions in legal immigration. Instead of giving DACA dreamers permanent legal status, they want to give them three-year renewable grants. When it comes to conventional immigration, they want to reduce current totals by "by 260,000 slots a year, or 25%. The libertarian Cato Institute, which is generally pro-immigration, says the reduction actually would be closer to 40%' which would be 'the largest policy-driven reduction in legal immigration since the awful, racially motivated acts of the 1920s.'"

Immigration is more complicated than economics, of course, but Seib's cautious and fact-rich piece may provide a model for a meaningful conversation between pro-immigration forces and restrictionists. If the latter want to make America great, they surely recognize that this is something that we can't do on our own. Underscoring the central role that immigrants play in a flourishing, growing economy while figuring out how to assuage the fears of immigration opponents—many of whom surely recall a parent or grandparent who was born elsewhere but died a "real" American—won't be easy, but it is necessary.

Show Comments (394)