John McCain: Iraq War 'Can't Be Judged as Anything Other Than a Mistake'

"I have to accept my share of the blame for it," the ailing senator writes in a new book, even while defending several other interventions and surges.

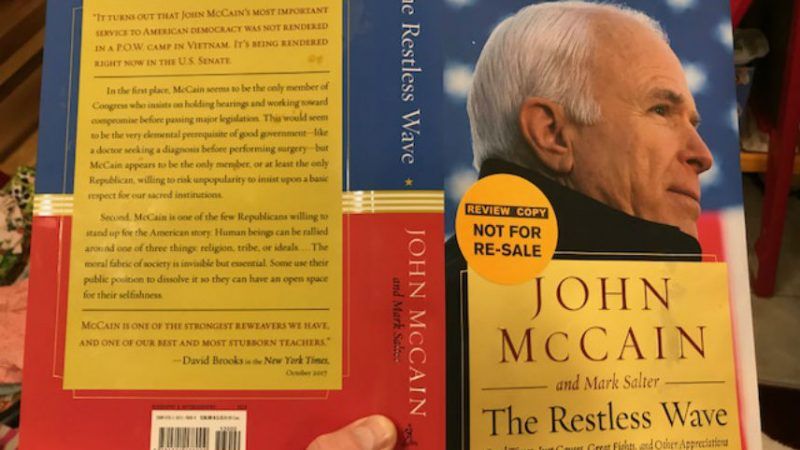

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), arguably the most influential post-Cold War hawk to never have worked inside the White House, makes a startling admission on page 107 of his soon-to-be-released book, The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights, and Other Appreciations.

"The principal reason for invading Iraq, that Saddam had WMD, was wrong," McCain writes along with co-author Mark Salter. "The war, with its cost in lives and treasure and security, can't be judged as anything other than a mistake, a very serious one, and I have to accept my share of the blame for it."

This marks a departure from McCain's historical stances on whether the war was justified. In his speech after wrapping up the GOP presidential nomination in March 2008—long after the lack of weapons of mass destruction was well established—McCain insisted that "I will defend the decision to destroy Saddam Hussein's regime as I criticized the failed tactics that were employed for too long to establish the conditions that will allow us to leave that country with our country's interests secure and our honor intact."

McCain spent most of the 2007-2008 election cycle focusing not on the original decision to go to war, but on President George W. Bush's unpopular counter-insurgency "surge" of U.S. troops, which the senator had been advocating for years. "The next president of the United States is not going to have to address the issue as to whether we went into Iraq or not," McCain said at his first debate with Barack Obama. "The next president of the United States is going to have to decide how we leave, when we leave, and what we leave behind." (Obama's counter: "John, you like to pretend like the war started in 2007…[A]t the time when the war started, you said it was going to be quick and easy. You said we knew where the weapons of mass destruction were. You were wrong. You said that we were going to be greeted as liberators. You were wrong. You said that there was no history of violence between Shiite and Sunni. And you were wrong.")

McCain's 2007 book Hard Call: Great Decisions and the Extraordinary People Who Made Them, rather than address the hard call to overthrow Saddam Hussein, limited that discussion to a single passage that was concerned chiefly with the consequences of faulty intelligence: "Leave aside the question of whether we would have invaded had we known the true state of his weapons programs: some have argued we shouldn't have; others, myself included, argued that Saddam still posed a threat that was best to address sooner rather than later."

As of 2013, the senator had moved to a more neutral position about the war's origins, while maintaining his usual position that things would be going a lot better if the U.S. maintained a more robust military presence in the region. "Was Saddam Hussein a long-term threat to the United States and his neighbors? Of course," he told the Arizona Republic then. "Was that justification to go to war? It's very difficult to assess that. But the tragedy of Iraq is that we had it won, thanks to the surge that began with David Petraeus in 2007, but this administration willfully arranged it so that there was no residual force left behind, and we are now seeing the unraveling of Iraq."

McCain's insistence that "every public official involved" in the decision to attack Iraq "has to accept responsibility for it" appears to be new, at least according to an initial search of public statements and my old files. But the maverick's enthusiasm for military intervention in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria has remained remarkably undimmed.

"All we can say for certain," he concludes in that section of the book, "is that Iraq still has a difficult road to walk, but another opportunity to progress toward that hopeful vision of a democratic, independent nation that's learned to accommodate its sectarian differences, which generations of Iraqis have suffered without and hundreds of thousands of Americans risked everything for." Such language could be cut-and-pasted from McCain speeches of more than a decade ago.

On Afghanistan, too, the senator's policy and rhetoric are almost wearingly familiar, and seemingly unaltered by the disappointing results of previous applications. "If you're going to commit American lives to a conflict, you must give them a mission they can win and the support they need to do it," he writes, sidestepping the original road not taken of declaring "mission accomplished" after overthrowing the Taliban regime. Instead, there's this update on his previous 50-100 years formulation:

The way to shorten a war is to make clear to the enemy you're going to do whatever it takes for as long as it takes to defeat them. The Afghanistan war has lasted more than sixteen years. It seems paradoxical to suggest that we can only win by committing to stay indefinitely, but that is the reality.

Thus McCain demonstrates one of the most fatal flaws of hawk-logic: It rarely takes into account the real-world constraints of American public opinion. Voter fatigue with never-ending war and perilous troop-deployment is part of the reason John McCain never made it to the White House, while such initial longshots as Barack Obama and Donald Trump did.

Having presidents less eager to use the military might make for frustrated political ambitions and poor policy outcomes, but it also provides an ever-ready excuse for when the interventions McCain champion turn out disastrous, as in Libya. "The U.S. and Europe, having intervened to change the regime, disengaged from the urgent, complex task of transforming a terrorized nation into a functioning civil society, of helping Libyans build national institutions where none existed," he complains. Yet despite all evidence that post-dictatorial, multi-sectarian, majority-Muslim countries in the Middle East and North Africa are not exactly promising candidates for America-led liberalism, McCain still believes: "There are many who still have faith they are capable of building a modern democracy. I do, too. I have met them, and been inspired by them, and believe in them. They need other Libyans to believe in their future, too, and assistance from the West to help them build it."

Then, after having lamented the lawless chaos of post-intervention Libya, McCain on literally the next page of his book agitates for a vigorous bombing campaign against Syria. There are rarely unintended consequences in these considerations, just insufficient resolve.

For someone whose entire lifespan, and those of his father and grandfather (and plenty of relatives besides, including two sons), has been marked by the fateful decisions of whether to go to war, McCain remains to his last days fascinatingly incurious about the implications of being wrong. As I wrote in a 2007 review of Hard Call:

Winston Churchill's pre–World War I conversion of the British navy from coal-fueled engines to oil is lauded. But once World War I is under way and he establishes a disastrous record in the Dardanelles campaign and on the shores of Gallipoli, we get only this: "I think Churchill was made a scapegoat for the mistakes and irresolution of others. But that is not a universal opinion and is perhaps best left for another book." As for the lasting geopolitical necessities brought on by the U.K.'s sudden and massive thirst for oil, which was at least partly responsible for the way Churchill drew the map of the modern Middle East, McCain is silent. […]

This pattern is repeated in McCain's other books and public utterances. In his 1999 memoir Faith of My Fathers, he describes his grandfather's time patrolling the Philippines during the long and bloody insurrection there as a Tom Sawyer–like adventure of swimming and fishing. He mentions that critics considered the 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic, which his father commanded, "an unlawful intervention" (and "with good reason"), but there the inquiry ends.

Nowhere is this historical incuriosity more evident than in McCain's public discussion of the conflict that concerns him most: Vietnam. When National Public Radio interviewer Terry Gross asked the senator in 2000 whether he would have still wanted to go to Vietnam had he known what he'd learned after coming home, McCain replied, improbably, "That question has never been asked of me before." […]

The biggest hint of any sort of intellectual exploration regarding Vietnam came in McCain's nine-month stint at what was then called the National War College in 1973–74. There, McCain wrote in an introduction to a recent edition of David Halberstam's history The Best and the Brightest, he "arranged sort of a private tutorial on the war, choosing all the texts myself, in the hope that I might better understand how we came to be involved in the war and why, after paying such a terrible cost, we lost." The results of McCain's Vietnam studies, therefore, have been of particular interest to those trying to pin down his evolution on questions of intervention, particularly during the time he was transitioning from orders-taking soldier to orders-giving civilian.

But McCain's April 1974 research paper, recently released after a Freedom of Information Act request, has absolutely nothing to do with how we got into Vietnam.

(That last tale is told here.)

Having McCain call the Iraq War a "mistake," and owning up to his responsibility for it, is certainly a welcome if belated tonic in our low age. The next step, for those who have shared the man's hawkishness, is to ruthlessly self-examine the aggressive mindset that not only led to the original errors, but arguably compounded them afterward. There are, at long last, limits to the applications of American power. Some waves would be better off a little less restless.

Show Comments (208)