The Hidden Legacy of Columbine: Ignorance About School Violence

On another National School Walkout day, 57 percent of teens are worried about dying in a school shooting. They shouldn't be.

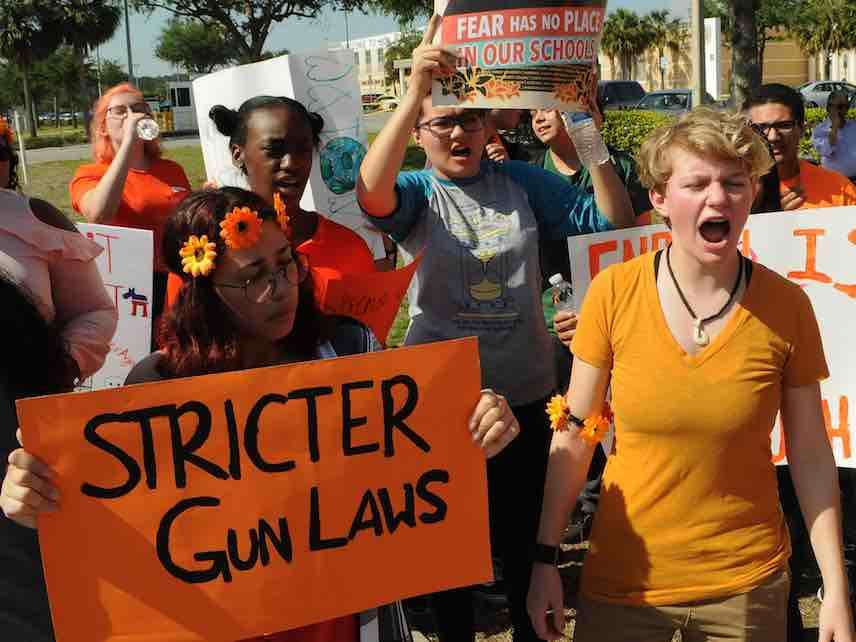

Today, on the 19th anniversary of the Columbine massacre, students around the country skipped classes as part of a National School Walkout to protest gun violence.

This is the latest attempt by survivors of the recent mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, to keep the public focused on school violence and on the various gun control proposals they believe would deter it. Invoking Columbine is meant to remind people that such attacks have been happening for decades, and to imply that this is because national leaders have continually failed to implement solutions.

But Columbine should teach us a different lesson: The press, the public, and policymakers are often ignorant, and doing the wrong thing can be just as counterproductive as not doing anything. In the wake of Columbine, so-called experts completely misdiagnosed the causes of the crime, and they decided to implement "safety" policies that gravely undermined students' rights without making schools any safer.

On April 20, 1999, two teenagers, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, marched into Columbine High School in Columbine, Colorado, and murdered 12 students and one teacher. They had planned to use explosives to kill many, many more, but their bombs failed to detonate.

Desperate for answers, the media quickly seized on "bullying" as its preferred explanation: Harris and Klebold were unpopular kids who had been brutally mistreated by their classmates, until finally they snapped and decided to shoot up the school as an act of revenge.

The journalist Dave Cullen has done excellent work debunking this and other myths associated with Columbine. No, Harris and Klebold weren't notably victimized by bullying. No, they didn't want revenge on specific students—they didn't specifically target jocks, Christians, popular kids, or any other group of students during their rampage. No, they weren't part of a cult. Neither comic books nor violent video games nor goth culture were responsible for the attack.

Harris, according to Cullen, was a true psychopath: He enjoyed hurting people because he hated them and thought himself superior. Klebold was depressed and suicidal, and he largely followed Harris's lead. As Cullen wrote in Slate many years ago:

What [Harris] was really expressing was contempt.

He is disgusted with the morons around him. [His diaries] are not the rantings of an angry young man, picked on by jocks until he's not going to take it anymore. These are the rantings of someone with a messianic-grade superiority complex, out to punish the entire human race for its appalling inferiority.

These distinctions might not seem like they matter much. But partly because of these fundamental misunderstandings, nationwide efforts to stamp out bullying intensified after Columbine. At the same time, zero tolerance policies—already growing more prevalent in the years immediately prior to Columbine, thanks in part to the 1994 Gun Free Schools Act—became even more popular, giving schools all sorts of means for expelling problematic, "bullying" kids. It's no wonder that by 2006 the school suspension rate was double what it had been in the 1970s. These trends were already underway before Columbine, but the massacre made them seem more necessary and intensified the push for them.

Schools also continued to employ more and more school resource officers to police hallways and classrooms. The federal Community Oriented Police Services office doled out hundreds of millions of dollars from 1999 to 2005 so that schools could hire cops. Columbine is not solely responsible for this, but the public's massive, sudden post-Columbine terror about violence in schools ensured that SROs and zero tolerance remained popular. This terror was largely unjustified, given that school violence—like most kinds of violence—was falling over this time period. But these policies were anything but harmless: Students have increasingly had to endure prison-like conditions.

Ignorance about the relatively low likelihood of school shootings is just as widespread today. I spoke with dozens of kids at the March for Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C., last month. Many told me that they were afraid of dying in school. According to the Pew Research Center, 57 percent of teens are worried about a school shooting. Here's how Vox highlighted this news:

A majority of American teenagers are now worried about being the victim of a school shooting—something that is no longer an uncommon occurrence in the United States.

But this is wrong. School shootings are no more common than they used to be, and might even be less common.

The media's exhaustive reporting on school shootings might make them seem more common, or especially deadly: The Washington Post recently reported that "in 2018 alone, there have already been 13 shootings." But many of those were accidents—a gun going off by mistake—and in nine of the incidents, no one was killed. Columbine-style violence remains blessedly rare.

Such widespread ignorance about school violence should make us skeptical that tragedy will inspire good public policy. It's certainly worth having a discussion about whether there are specific policies that might reduce gun deaths—particularly the most common kinds of gun deaths, which are suicides, not school massacres. But anyone making such a proposal must reckon with the fact that since the '90s, as it has become easier for most Americans to obtain a gun, America has become safer for both adults and kids.

Show Comments (115)