81 Federal Prisoners Have Died While Waiting for the Government to Decide If They Were Sick Enough to Go Home

The Justice Department has finally shared data from the "compassionate release" program, and the numbers aren't pretty.

Since 2014, at least 81 elderly and terminally ill federal prisoners have died while waiting for the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to rule on their applications for "compassionate release," according to a letter the Justice Department letter sent to 12 members of the Senate. The letter was obtained and published by Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

"We are disappointed but not surprised," says Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM).* A nonprofit devoted to sentencing reform, FAMM is pushing the BOP to reduce the sentences of elderly and ill prisoners.

Congress created compassionate release in 1984, the same year it abolished parole in the federal system, in order to provide the Bureau of Prisons with a systematic method for shortening the sentences of federal prisoners whose "extraordinary and compelling" circumstances merit early release. No list of criteria constrains the BOP's ability to grant compassionate release.

Two years ago, The Washington Post profiled several federal prisoners who seem like textbook candidates. One of them was a nonviolent marijuana trafficker named Michael Hodge who applied for compassionate release after being diagnosed with metastatic cancer. His request was denied, and Hodge died behind bars in 2015. Bruce Harrison, 65, also had his request denied. Sentenced in 1994 to 50 years for delivering drugs on behalf of undercover federal agents, Harrison, a recipient of two purple hearts during the Vietnam War, now suffers from neuropathy and vertigo. "Compassionate release is conspicuous for its absence," declared the authors of a 2012 report from Human Rights Watch.

If people like Hodge and Harrison aren't receiving compassionate release, who is? We don't know. Unlike commutations and pardons, which are approved by the President and published in detail by the Office of the Pardon Attorney, the review and approval process for compassionate release is a black box. That's why 12 senators sent a letter last August to the Justice Department requesting five years' worth of data about the compassionate release program. A month earlier, Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.) inserted language into the appropriations bill requiring the DOJ to reveal how many prisoners died awaiting a response, how many applications had been granted and denied, and how long prisoners had to wait on average before receiving a response.

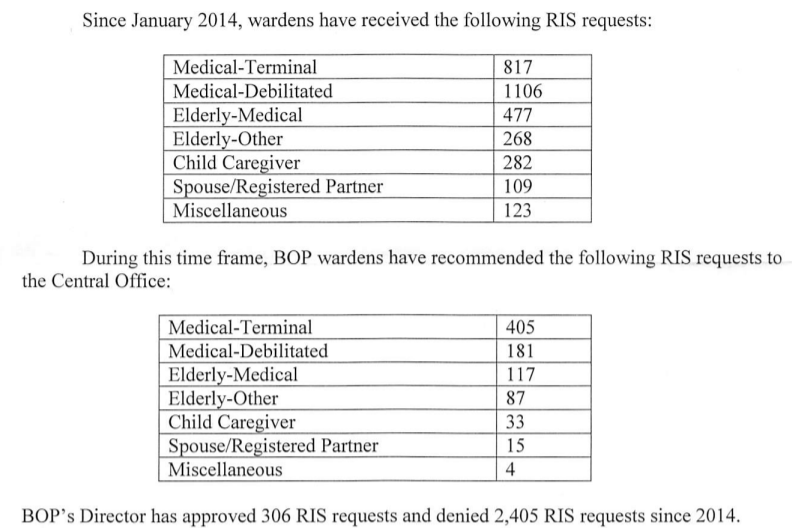

The DOJ's letter answers many of these questions. In addition to the 81 prisoners who died while waiting for a response, the letter reveals that the BOP Central Office has has denied 2,405 compassionate release requests since 2014. BOP wardens recommended nearly three times more reductions in sentence (RIS) than were granted by the BOP Central Office in Washington, D.C.: 842 warden recommendations compared to 306 grants from the BOP's Central Division.

The DOJ's letter also omits the subcategories for grants, despite sharing them for requests:

"The local warden and his or her staff know best which prisoners in their care merit early release," Ring tells me. "The fact that central office bureaucrats are rejecting so many petitions sends a terrible message to the wardens who are trying to do the right thing. Wardens should be encouraged to identify sick and elderly prisoners who can be safely released. Early release will help ease overcrowding and save money. But if the people on the ground making smart recommendations are just going to rebuffed by Washington, they will stop trying."

While the DOJ told the senators what kind of requests the BOP Central Office received, it declined to share the criteria that led to grants. Were all 306 grants for terminal illness? If so, why did the Central Office deny the additional 100 terminal illness applications recommended by wardens? Did the BOP grant any compassionate release sentence reductions for chronically ill or physically disabled prisoners? What about prisoners whose children lost a parent and needed a breadwinner? And what's happened to 817 medical-terminal applicants who've applied since 2014? It seems to assume that however many are not among the 306 are now dead.

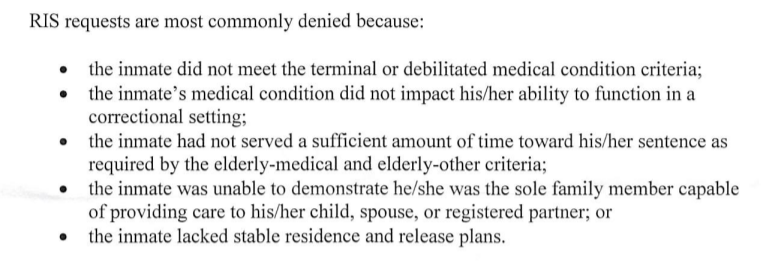

The DOJ also revealed common reasons for denying compassionate release requests. Some of these rationalizations are pretty horrifying:

The inmate wasn't in prison long enough to deserve not to die there? The inmate was capable of functioning in a prison setting despite their illness? Go click the link for that Washington Post story and look at the pictures, and then tell me the BOP's definition of "ability to function" is not outrageously broad.

The letter also reveals that the BOP has no sense of urgency for these cases. Processing times for grants averaged 141 days—nearly five months—while denial processing times averaged 196 days, almost seven months; that's too much time for terminally ill prisoners and for people whose home lives have deteriorated to the point that the bureau would allow them early release. In fact, requiring prisoners to wait that long, especially if their applications come recommended by a warden, defeats the purpose of the program. We know the department spent too much time deliberating for at least 81 prisoners. Congress should ask the department how many more people died after receiving a rejection, whether they were serving time for a drug offense (as half the federal prison population is), and why those prisoners were not granted the small mercy of dying outside a cage.

*Full disclosure: I served as FAMM's communications director from 2014-2016.

Show Comments (37)