Like Schools, Parks, Social Programs? Too Bad, Because Retirees Get Paid First

New report shows how California's pension obligations are crowding out spending on other things.

Increasing pension obligations will slowly strangle schools, parks, and civil services in California. The rest of the country might not be far behind.

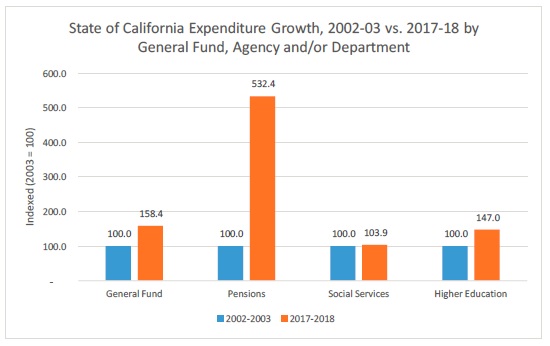

As recently as 2003, California's state government paid about $1.3 billion towards the state's two biggest pension funds—CalPERS, which funds retirements for state workers and public safety employees, and CalSTRs for the state's teachers. This year, the state will spend more than $8.7 billion on those two pension funds. By 2030, those annual payments will exceed $19 billion, according to projections in an extensive new report released this week by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Those increasing costs, the Stanford report says, cannot be covered without significant cuts to existing government programs. Because some education spending is fixed under California's Prop 98 rules and public safety funding cannot be cut under other state rules, there are few options other than reductions to other services.

"Pension costs have crowded out and will likely to continue to crowd out resources needed for public assistance, welfare, recreation and libraries, health, public works, other social services, and in some cases, public safety," says Joe Nation, the author of the report and former Democratic member of the California state assembly.

Compounding the state-level pension crisis, local governments are facing similar straits. The Stanford report includes case studies for more than dozen cities, large and small, across California.

In Sacramento, pension costs are projected to hit $150 million by 2023, up from $42 million in 2008. Pension costs have already forced cuts to its cultural programs, neighborhood services, transportation, and police, Nation says. By 2030, the increasing costs will require eliminating $94 million in non-pension spending—equal to a 25 percent reduction in both police and fire expenditures, or 10 percent across-the-board expenditure reductions.

California is in many ways the poster child for America's ongoing public employee retirement crisis, but it is by no means alone. Major cities across the country are facing the same difficult choices.

Using data from Merritt Research Services, Governing Magazine determined that American cities with a population of more than 500,000 spend, on average, about a quarter of their budgets on debt service—including payments to pension system and other so-called "legacy costs" like retired public workers' health care costs. That percentage isn't necessarily concerning, but what's more worrisome "is that legacy costs are rising, taking up ever-larger shares of budgets," writes Mike Maciag, Governing's data editor.

Annual budget outlays for debt payments, pension costs, and other post-employment benefits for cities in Governing's analysis have crept upwards from about 20 percent in 2011 to more than 22 percent in 2016. In some places, the increase has been much greater. "The trend continues to squeeze out other operating expenses over time," Richard Ciccarone, president of Merritt Research, tells the magazine. "Many cities are going to have to increase taxes to retain current levels of services."

Even with the rosiest assumptions, pension costs will continue to rise through at least 2020, warns Moody's Investors Service. State and local governments have more than $4 trillion in retirement debt on their books, the credit rating agency determined in a June analysis. Thomas Aaron, Moody's vice president, says governments will have to increase spending by 17 percent to keep pace with pension costs.

Americans will make do with fewer government services—the silver lining of all this is that increasing budget pressure is a good way to force cuts of wasteful and ineffective programs—but the pension crisis will only reduce the scope of government, not the cost of it.

Show Comments (33)