Makers of 3D-Printed Guns Follow In DIY Tradition of Ammunition Reloaders

Reloaders and DIY gunmakers alike are motivated by innovation and a willingness to make for themselves what the government doesn't want them to have.

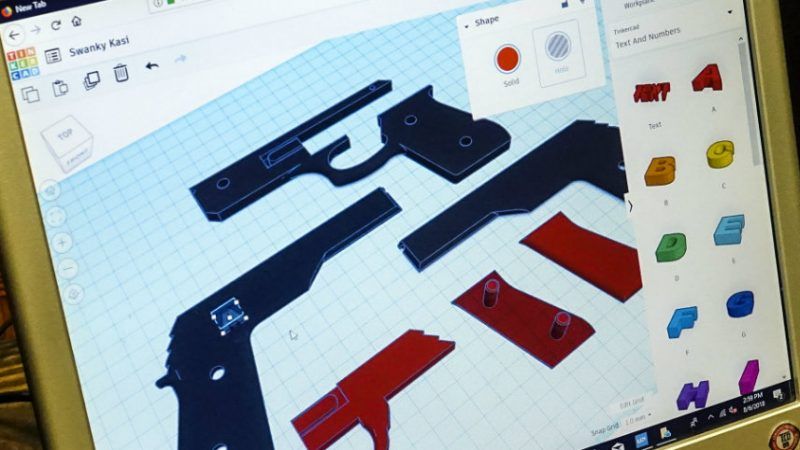

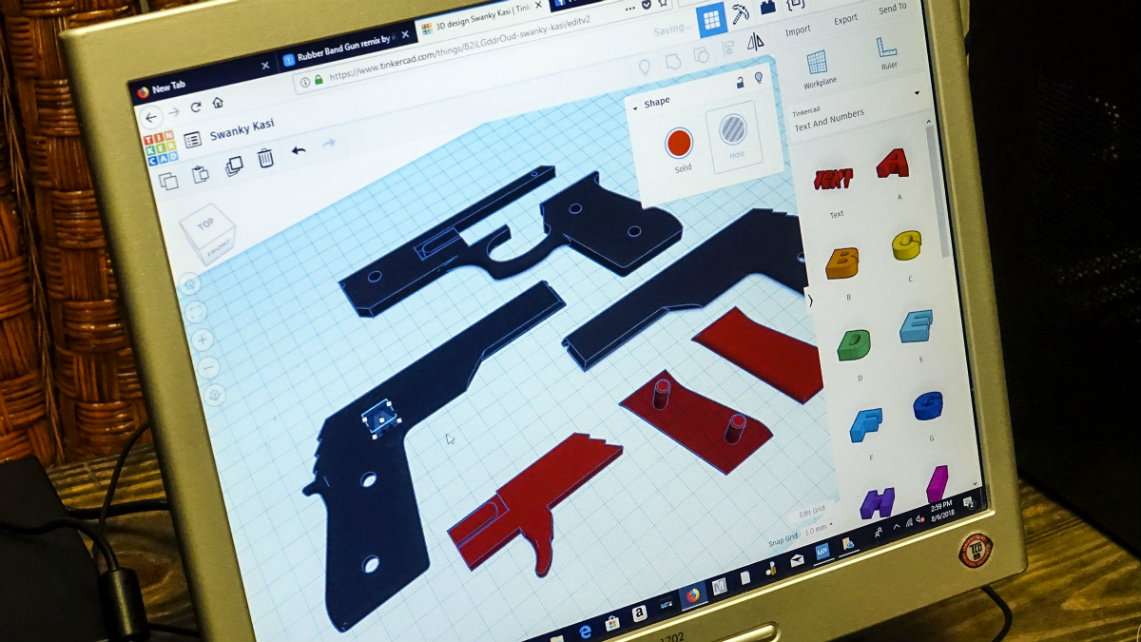

To the disappointment of control freaks, DIY gunmaking is rolling along strong despite Defense Distributed's Cody Wilson facing charges that he had sex with a 16-year-old. One man does not a movement make, not when he can be replaced by a British convert to the cause such as Paloma Heindorff, who has stepped in to lead Defense Distributed. But not only is home gunmaking doing just fine without the man who launched it into national headlines by making the first 3D-printed gun, what is perhaps the biggest DIY weapons community—that of ammunition reloaders—is surging along, too.

With roots dating back to black powder shooters casting bullets by the campfire, and spurred by ammunition shortages and regulations, people who make their own ammunition quietly demonstrate a desire to place themselves beyond the reach of the state. That ethos should ring a bell with anybody who has ever contemplated purchasing a 3D printer, just in case.

"About five million out of roughly 43 million hunters and sport shooters in the United States make their own bullets and shells," The New York Times reported earlier this month, in one of the media's periodic rediscoveries of this expression of the spirit of self-reliance.

The estimate of the number of shooters is probably on the low side for a country that the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey tells us owns about 46 percent of the world's 857 million privately held firearms. But the popularity of reloading is unquestionable.

I saw it myself at a gun show a few years ago when attendees vacuumed up brass cases, powder, and other reloading supplies in response to a shortage of commercially available ammunition. (Fortunately, I'm pretty well-stocked at home.) That shortage spurred plenty of people to rediscover their inner craftsmen. "[T]he scarcity of ready-made bullets has frustrated shooters to the point they're spending between $200 and $1,000 to get into the hobby known as 'reloading,'" NPR noted at the time.

If you're a serious hobbyist shooter, that cost might not seem all that daunting. It's not difficult to blow through the equivalent expense in commercial ammunition in a few sessions at the range. Loading your own doesn't eliminate the expense, but it can lower it—and provide increased access not only to ammunition, but to loads customized for personal needs.

Those are do-it-yourself benefits discovered a very long time ago.

"Prior to the development of the cartridge case, shooters usually kept a possibles bag that contained black powder (often in a powder horn), flash powder or caps, a bullet mould, patches, lubricant and other necessary items to reload and maintain their guns," Handloader magazine related in a 2016 history of the practice.

Early shooters' skills remained relevant with the introduction in the 1870s of self-contained center-fire cases. Commercial ammunition was expensive when it was available at all. But brass cases could be reused, lead melted, primers hoarded, and powder acquired from a variety of sources. Powder and other components improved in sophistication, but the basics of reloading were in place in the 19th century—there's little a shooter at a bench can do today that wouldn't be recognizable to Wild West-era counterpart.

"More retro than futurist, more low-tech than high-tech, casters and reloaders tend to be older and often retirees," the Times piece pointed out. "In contrast, those interested in creating printable guns are often younger and more internet savvy."

But reloaders and DIY gunmakers have rather more in common than that characterization suggests.

Both "share a staunch skepticism of the government and an ideological individualism that have long been hallmarks of the broader American gun ethos," the Times continued. "many in this group think of themselves as social disrupters, questioning the relationship between citizens and their states. In their view, guns are not just a constitutionally protected right, but also a socio-historical symbol whose very purpose is to level the playing field."

Whether or not they're the actual offspring of the reloaders casting bullets and measuring powder on a garage workbench, the people tinkering with 3D printers and CNC machines are the philosophical heirs to men and women laboring over reloading presses. The chosen means of expression may have more to do with the fact that, until recently, the cost-savings and customization of reloading were more compelling to most shooters than the sense of accomplishment in home gun manufacture.

Politicians have set themselves to changing that dynamic though. While gun laws in some states have loosened to respect individual rights, others have tightened in an effort to choke off civilian access to the means of self-defense. And officials sponsoring those restrictions recognize the threat DIY efforts pose to their plans.

"These 3D-printed weapons will be used to evade Massachusetts' strong gun laws, and my office and our law enforcement partners will do everything we can to keep deadly homemade weapons off our streets and out of our schools," Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey sniffed in August.

The same logic applies to the ammunition that feeds those weapons, as is apparent to shooters. Several sellers of reloading components explicitly argue that "by reloading your own firearm, you can avoid ever-changing, restrictive gun laws."

Logically enough, the DIY gun and ammo worlds are bridging whatever cultural gap may ever have divided them. The Times described a reloading enthusiast who believes he has designed a round that will work better than traditional ammunition in relatively fragile 3D-printed guns. He even envisions a future in which printed firearms are disposable, like current pepper spray canisters.

That may or may not come to pass. But it illustrates the point that it's not gee whiz technology that drives weapons tinkerers. Rather, reloaders and DIY gunmakers alike are motivated by innovation, self-reliance, and a willingness to make for themselves what the government doesn't want them to have.

Show Comments (56)