Vietnam and the Rise of White Power

A new book ties racist reactionary politics to the war, but overreaches when it comes to militias.

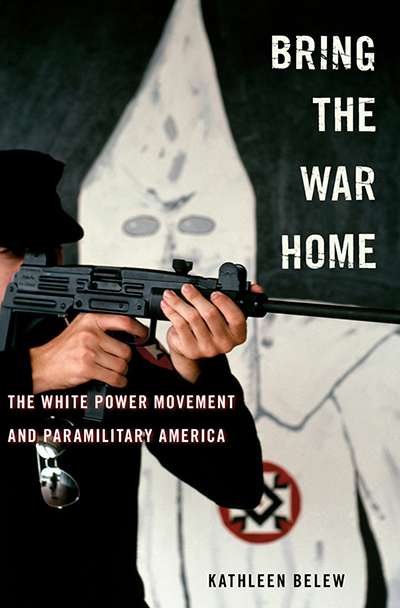

Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, by Kathleen Belew, Harvard University Press, 339 pages, $29.95

America's defeat in Vietnam produced a surge of men who felt betrayed by the federal government and who feared communism's spread to the United States. Further incensed by government scandals, economic struggles, and a changing cultural landscape in the wake of the civil rights movement's successes, some of these men sought to regain control through white power organizations.

So argues Kathleen Belew, a historian at the University of Chicago, in Bring the War Home, an engaging account of how and why the modern white power movement emerged from 1975 to 1995. By Belew's account, the movement encompasses the Klan, white separatists, neo-Nazis, and even radical tax resisters. Her research is thorough: She compares news reports, government records, and materials from the groups she studies to cross-check her analysis. Her argument falters, though, when it treats the militia movement of the 1990s as an "outgrowth" of this racist milieu rather than a separate movement with its own origins and concerns.

Belew is not the first writer to argue that the defeat in Vietnam helped fuel the growth of a new kind of reactionary politics. But she offers an unprecedented level of detail, engaging deeply with developments that other authors typically gloss over. Take her analysis of how white power activists sought out mercenary experiences in Latin America. (Klan leader Don Black, for example, was part of a failed effort to initiate a coup in Dominica. The aim was both to protect the U.S. from allegedly encroaching communism and to filter money to white power groups at home.) She links these members' decision to become mercenaries to tactics (such as booby traps), weaponry (such as AK-47s), and ideas (such as anti-communism) they associated with the Vietnam War. Through such shared concepts, Vietnam stayed relevant in white power circles long after the conflict ended.

A few other authors have mentioned white power figures' mercenary work and their lack of legal accountability for possible crimes committed along the way, from violations of the Neutrality Act to involvement in civilian massacres. But Belew alone shows these men's impact on the movement, as opposed to merely demonstrating their violent dedication to it. The mercenaries wanted to physically enact a redemption from the loss in Vietnam—in Belew's words, to "redeem the defeat." More radically, some prepared themselves to use these same techniques of war on home soil against a federal government they saw as increasingly hostile to their interests. Examples include a foiled plot to bomb an embassy and several groups' paramilitary activities at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Belew's analysis unfortunately outsteps its supporting data when the book reaches the 1990s. The author argues that militias—groups of mostly white, mostly male Americans who feel a civic duty to be prepared to defend the country from any threat—represent the "peak" of the white power movement because of their size.

As a sociologist who studies the contemporary militia movement, I think Belew overstates the connection to white power groups. My research and the work of several other scholars indicate that the racist right and the militias had separate aims and identities.

Some white power organizations did overlap somewhat, both in membership and in ideas, with some early militia groups. But as Belew herself notes, militia recruits "could, theoretically, participate in a local militia without deliberately participating in the white power movement." This is because, unlike white power organizations, most militia groups' aims were not racially oriented. Instead, they focused on gun rights and the federal government's size and power.

Belew rightly rejects the idea that a social movement needs a single leader or unified message. But distinct movements that share select interests or pool their resources under the right circumstances can maintain separate identities. This framework can be envisioned as a Venn diagram, where groups with different core characteristics have some, but not all, ideas, members, or other resources in common. For example: Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, the Sierra Club, and other movements on the left have recently coordinated with the Women's March against the current presidential administration.

In the case of white power groups and militias, the shared "field" of common interest was a perception of government overreach and abuse, particularly following the standoffs with Randy Weaver's family at Ruby Ridge in 1992 and with the Branch Davidian sect in Waco in 1993. Needless to say, this field was shared far beyond both movements, bringing in mainstream Americans across the political spectrum.

Belew's evidence for treating the militias as an outgrowth of the white power movement largely rests on two points. The first is that militia groups in Idaho and Montana had racist orientations. But most militia scholars recognize the Idaho Christian Patriot group as an overtly religious and supremacist organization—and while the Militia of Montana included "militia" in its name, it had no firearms proficiency requirements and little in the way of formal military-style training, both of which rapidly became central to other militias' identities.

The second piece of evidence relates to conservative radio host and conspiracy theorist Mark Koernke, whom she identifies as a Michigan Militia leader. Koernke successfully framed himself that way, but his name is absent from the original 3,000-plus pages of fax records—including lists of leaders—provided to me in 2010 by Michigan Militia founder Norm Olson. Members who were active in the '90s described Koernke to me as a "wannabe Alex Jones" who had little interest in anything except his own status, which he severely damaged by jumping into a lake while running from police searching for an unrelated marijuana grow.

Belew mentions a possible connection between Koernke and Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, although unlike many authors, she is careful to note that McVeigh merely attended some militia meetings rather than calling him a member. To demonstrate the McVeigh-militia connection, Belew cites a 1995 news article where unnamed witnesses recalled that McVeigh had acted as Koernke's bodyguard a year prior. At least one journalist—ABC's Jonathan Karl, then of the New York Post—has reported that this was a case of mistaken identity, and that Koernke's bodyguard was actually a man named McKay. But even if the McVeigh report is true, it says more about Koernke and his small personality cult than it does about McVeigh's relationship to the militia movement as a whole. Koernke has a reputation for maintaining unpaid "bodyguards," drawing when he can from veterans and others he perceives as boosting his own status by proximity.

There is also evidence that groups under the white power umbrella tend not to accept militias as part of their movement. White Aryan Resistance founder Tom Metzger (a recurring figure in Belew's book) stated his opinion of the militias in 2001: "They are mostly uniform freaks that wanted to play war. The minute McVeigh committed a real act of war, the militias disappeared quickly. Most backtracked [on their anti-government ideology] and affirmed allegiance to the Iron Heel. Most now work directly with the FBI." Similar rants can be found in other publications from the '90s and on online message boards through the present day.

Treating the militias as a separate movement may seem like splitting trivial academic hairs, but the distinction has practical importance. Research suggests that overbroad labeling, especially from law enforcement, can help push people into violence or other extremism. A notable example came when the Department of Homeland Security released a report on "rightwing extremism" in 2009 that called the militias "violent," and that offended veterans by warning that former soldiers may be susceptible to terrorist recruitment. Attendance spiked at Michigan Militia events immediately following this report, and leaders of other states' militias reported the same response—presumably the exact opposite of what the writers had intended.

The label "white power" carries a race-focused orientation that isn't present in the militia movement as a whole. Applying it to nonracist militias undermines our understanding of both movements, making it harder to use our limited resources to address racism and extremist violence. But despite these problems, Bring the War Home is an excellent resource for anyone interested in the history of America's white power movement—whether for academic pursuits or to inform opposition to white supremacy. I wish the book had been available when I started my own studies in this area.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Vietnam and the Rise of White Power."

Show Comments (80)