California Mulls Bail Reform

As the state legislature reconvenes, getting rid of cash bail will likely be on the table.

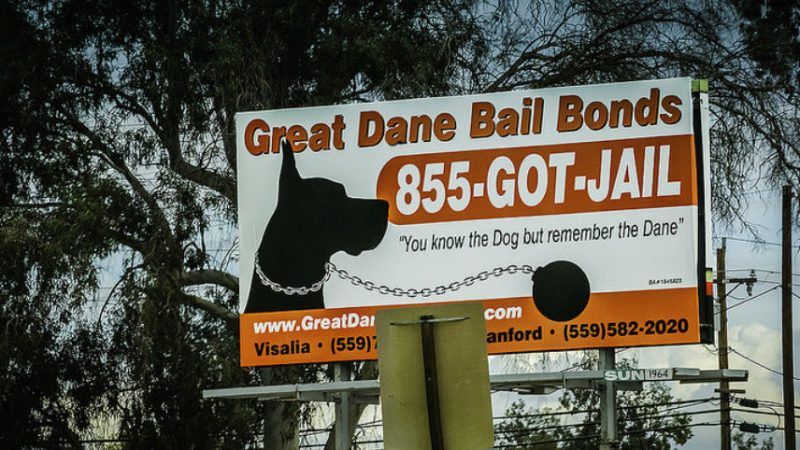

Facing an existential threat to their business model, California's bail-bonds industry worked last session to derail two bills that would have changed the way the state deals with people who have been accused of crimes, but are awaiting trial. Opponents even brought out the colorful reality TV star, Duane "Dog the Bounty Hunter" Chapman, to make the case that the Assembly should kill the bill that was on the table.

Nevertheless, California again is moving forward with plans to largely do away with the "money bail" system. Even though the bills ultimately were shelved, they are likely to come back now that the state legislature has reconvened. The reform effort has since gained a boost from two important sources—a working group established by state Supreme Court's Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, and from Gov. Jerry Brown (D), who issued a statement in August promising to craft a "cost-effective and fair" reform to the bail system.

The reason is obvious. The current process is fundamentally unjust, as it too heavily relies on an accused person's financial status—rather than flight risk and danger to the public—to determine whether that person goes home or stays in jail. It also hammers California's taxpayers. The bail-bonds industry touts its efforts as cost effective because private insurers underwrite these bonds—and then private "recovery agents" track down those who go on the lam.

Yet they neglect to mention the enormous costs to taxpayers of housing so many people during pretrial detention. According to a UCLA School of Law study from May, California jails 59 percent of those people accused of crimes compared to 32 percent nationwide. Such pretrial detention, for instance, costs $204 a day in Santa Clara County compared to $15 a day when the accused are released as part of a pretrial supervision program.

But the main public policy issues involve justice and public safety. The current bail system fails both of those tests, as well. With money bail, a person accused of, say, voluntary manslaughter might be required to post bail of $100,000. If the person has that much cash in the bank, he or she could provide that amount to the court and get it refunded after showing up for trial.

More commonly, the person will pay 10 percent to a bail-bonds company, which posts a bond guaranteeing the full bail amount if the accused is released and then hops a bus to Guadalajara. That's nonrefundable. Bounty hunters (such as "Dog") track down the folks who run away. It makes for good TV, perhaps, but it's not a good way to administer a justice system based on a presumption of innocence.

Most people who are accused of crimes don't have the money to bail themselves out, nor do their families. A wealthy person accused of a serious crime can post bail and go home. A poor person accused of a lesser crime will languish in jail. The court process can be excruciatingly long. Those who wait in jail are three times more likely to be sentenced to prison than those who post bail, according to reports.

The reason is simple. If you were accused of a crime, but didn't have the money to get out, you'd be far more likely to accept a plea deal—any plea deal—so you could get back to work, or get back to your kids. How do you pay the rent or car payment while you're sitting in a county jail? The prosecution already holds most of the cards in the criminal justice system, and this system gives prosecutors a winning hand.

Public safety should of course be the first concern. After New Jersey passed reformed its bail system, "the state's jail population has fallen by 15.8 percent, while crime has decreased 3.8 percent and violent crime by 12.4 percent," according to my R Street Institute colleagues Arthur Rizer and Caleb Watney, writing in USA Today in September.

It's reasonable to think that a pretrial release system based on a "robust risk-based pretrial assessment and supervision system," as the California Supreme Court's working group explained, actually could improve public safety. The group explains that these pretrial programs "give judges more tools to supervise defendants, such as drug testing, home confinement, and text reminders for court dates." Such a system also gives judges more power to keep potentially dangerous people behind bars.

The UCLA study found myriad problems with the current commercial bail-bond industry. The study noted, as we saw during last session's hearings, that it "has exerted significant political influence through organized lobbying, fueling growth in the use of money bail and curtailing the expansion of non-monetary pretrial release mechanisms."

That's to be expected. Every interest group has an incentive to lobby and contribute to political campaigns. But legislators need to listen more to the evidence and less to emotional appeals offered by self-interested parties.

This article first appeared in the Orange County Register.

Show Comments (19)