How America's Outdated Tax Code Fails Gig Economy Workers

More people are working in the gig economy than ever before, but the current tax code punishes Uber drivers and Airbnb hosts. Here's how Congress can fix that.

When Congress last passed broad tax reform legislation, in 1986, no one had ever heard of the "sharing economy."

It would be more than a decade before eBay and Amazon, the first major precursors of the idea that you could run a business with nothing more than something to sell and an internet connection, would appear on the scene. Companies that would later become synonymous with the sharing economy (or the "gig economy," as it's also known), such as Airbnb and Uber, were more than two decades away.

But in 2017, as Congress mulls a rewrite of the federal tax code for the first time in more than 30 years, people earning money from gig jobs tied to smartphone apps are a large, and growing, part of America's workforce.

"The current tax administration system isn't working for a significant percentage of on-demand platform small business operators," says Caroline Bruckner, managing director of the Kogod Tax Policy Center at American University. "These tax compliance challenges are only going to continue to grow and impact more and more self-employed small business owners."

Tax reform could be the centerpiece of Congress' fall agenda. While most of the discussion will focus on top marginal rates and the promises of faster economic growth or reduced inequality, a less-noticed but crucial part of the discussion will involve changing the tax code to match the needs of an economy that includes more independent contractors and freelancers, thanks to the rapid growth of gig economy platforms in recent years.

The current federal tax code puts those workers at a disadvantage in several ways. Ambiguity in the tax code has led to different interpretations about IRS reporting standards for workers earning money through gig economy platforms. Even though the current tax code contains loopholes that exempt potentially tens of thousands of dollars of income from some part-time independent contractors, navigating it can be complicated and costly for workers who use Uber or Etsy to earn a relatively small amount of extra income. Taken together, these problems can leave sharing economy workers with huge tax bills, potentially forcing them to seek expensive professional tax help, while simultaneously hampering the federal government's ability to collect tax revenue.

As talk of tax reform heats up in Congress, lawmakers have an opportunity to update the tax code to account for the growth of independent contractors and peer-to-peer employment, a trend that is unlikely to reverse in the coming decades. If lawmakers make small expansions to existing protections for low-dollar work of this type, it could save the majority of gig economy workers from costly tax issues, while making the tax code fairer and likely increasing revenue collections.

"Everyone is losing under the current rules," says Bruckner. "Both on-demand economy players and the IRS deserve greater efficiency and less hassle. We can do better."

II.

For new Uber and Lyft drivers trying to figure out the complexities of the federal tax code, ride-sharing can quickly turn to cloud sourcing. Websites like UberPeople.com and subsections of Reddit and other online message boards are used to swap stories, give advice, and, yes, complain about taxes.

"Why must the tax code be so stupidly complicated?" wrote user "New-Ber X" in one rather typical post on UberPeople.com's "Taxes" section. It was December 2014 and the 33-year-old woman from Chicago had only been driving for Uber for a few weeks, but she was already looking ahead to the following year's tax season. "I know that full-time Uber Drivers are typically classified as independent contractors and are required to pay quarterly estimated taxes once they pass a certain profit threshold," she wondered. "However, is that still the case for someone who has a full-time, 40+ hour job and is just doing Uber on the side for extra cash?"

The responses were about what you'd expect from complicated tax questions posed to an open online forum: a mixture of bad and potentially helpful advice, along with arguments between respondents about which are which. "Please contact an accountant," was probably the best—or at least the clearest—piece of guidance.

As Congress mulls a rewrite of the federal tax code for the first time in more than 30 years, people earning money from gig jobs tied to smartphone apps are a large, and growing, part of America's workforce.

Though some workers in the gig economy rely on Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Etsy, and the rest for all their income, New-Ber X's situation—working a full-time job and driving for Uber on the side to make a little extra dough—is a more typical arrangement. Under the current tax code, though, "just doing Uber on the side for extra cash" can land workers in a confusing, and potentially quite expensive, tax situation—one that often requires the assistance of a tax professional, or at least many extra hours of unexpected work.

When researchers from Boston College Law School surveyed online forums for Uber and Lyft divers in the spring of 2016, they found that similar confusion abounds. While most of the 800 online commenters surveyed "seemed to understand the basic requirement that they pay taxes on rideshare income," they concluded, many were confused about how to report that income or about how various deductions in the tax code applied to them. Almost all—including "New-Ber X," whose comments on the UberPeople.com message board were highlighted in the Boston College report—were new to being independent contractors.

Workers who earn a salary or hourly wages get a W-2 from their employer at the end of the year and use that information to fill out their federal income tax returns. Because almost all W-2 employees have income taxes withheld during the year, it's usually straightforward and even, maybe, somewhat rewarding when the government refunds some of their money.

Being an independent contractor is very different. This group has its income reported on a 1099 form, and usually does not have income taxes withheld. Additionally, independent contractors are on the hook for both halves of the federal payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare, while W-2 workers have half of those taxes covered by their employers.

Adam Gorlovsky-Schep, a Boston-based certified personal accountant, estimates that 80 percent of his clients who have income from Uber, Airbnb, and the like are using those applications as side gigs to make a little extra money—not as their main source of income. But that distinction means nothing to the IRS, which views all independent contractors the same way, whether they're earning hundreds of thousands of dollars a year running a business or making a few thousand dollars with ride-sharing or room-sharing.

"Paying taxes is perhaps the most obvious challenge faced by contractors," says Arjan Schütte, a senior advisor to the Center for Financial Services Innovation, a nonprofit focused on improving the policy landscape for entrepreneurs and investors. "Where individuals freelance by necessity or choice, 1099 status imposes unique financial complexities and pain points."

Those problems are faced by anyone who freelances—whether on the side or for a living—thanks to a federal tax code that incentivizes W-2 employment despite growing numbers of independent contractors. But independent contractors working in the gig economy face further complications from the fact that not all gig economy platforms operate the same way when it comes to reporting income to the IRS.

Under current law, payments for more than $600 to independent contractors or other non-employees are reported to the feds via Form 1099-MISC, and a copy of the form is also provided to whomever earned the income. But if payments are made via credit card—as many transactions in the gig economy are—and those payments exceed $20,000 or the number of transactions exceeds 200, they are reported via Form 1099-K. Banks and other "merchant acquiring entities" must report all payments no matter the amount, while "third party settlement organizations" must only report transactions exceeding the $200,000 threshold.

Yes, it's confusing. It gets more confusing if you're on more than one platform. Uber, for example, issues 1099-K forms to all employees, while Lyft operates under the "third party settlement organization" rules and only reports payments above the $200,000/200 transaction threshold.

The Boston University researchers, based on their review of message board tax confusion among new Uber drivers, concluded that some first-time 1099-K recipients may have over-reported earning on their tax return because Uber reported gross earnings (including things like Uber's commission on fares, tolls, and other fees that are deductible from a driver's taxable income). Some drivers may not be aware that they should report their gross amounts on the Schedule C of their tax form but then deduct a variety of expenses from that total. "This exercise is complicated," the Boston University team concluded, and "while savvier posters seemed to eventually get it right, we do not know whether the less savvy ones did."

In a report published with colleagues at American University earlier this year, Bruckner found that about 60 percent of 518 gig economy workers surveyed said they never received forms that would notify the IRS of their earnings. Most of them surely did, but either didn't understand what they needed to do or chose to ignore the mail.

"The inconsistent reporting rule adoption among on-demand platform companies creates confusion among taxpayers," says Bruckner. It's a problem that has arisen because the tax code has fallen out of step with the modern economy. That part of the tax code was written when independent contractors were unlikely to be paid via credit card transaction—indeed, before credit card transactions were anywhere near as common as they are today.

The tax bills can add up fast. A driver who earns $7,500 in a year (what the average Uber driver made in 2015, according to company data) would owe $1,060 in self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare, enough to trigger mandatory quarterly payments under IRS rules—another complication few gig economy workers will expect. "It just doesn't take that much income to trip over these filing requirements," Bruckner says. Not making quarterly payments—and waiting instead for normal end-of-year tax filing time, as most Americans do—can result in penalties and an even bigger bill.

The best way to get an answer to these questions is to talk to a tax professional, but that's expensive and time-consuming—potentially too expensive and time-consuming to be worth it if you're only making a small amount of money in the gig economy.

"Everyone is losing under the current rules. Both on-demand economy players and the IRS deserve greater efficiency and less hassle. We can do better."

Beyond the cost of such services, there is a generational divide. Millennials comprise the largest share of workers in the gig economy—68 percent of them, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center published in February. On the flip side, millennials are the least likely group, generationally speaking, to have access to tax help, according to a 2016 survey from NerdWallet, a San Francisco–based personal finance website.

"Millennials tend to have less experience with a deeply confusing tax code, less cash to seek professional help and less need for the more complicated returns that having children or a mortgage can bring," says Liz Weston, a personal finance columnist at NerdWallet.

III.

The cost of confusion about the tax code goes well beyond the tax bill itself, which is unavoidable. But there is opportunity cost in the time spent tracking down answers to difficult questions, or the expense of hiring someone to walk you through the whole thing. The IRS is unlikely to be of much help. During the 2015 filing season, only 37 percent of taxpayer calls were routed to a customer service representative, and the average hold time for those calls was 23 minutes, according to the National Taxpayer Advocates' annual report.

Martin A. Sullivan, chief economist for Tax Analysts, a Virginia-based nonprofit organization that publishes Tax Notes, an online newsletter focused on news and commentary of tax policy issues, says most gig economy workers have no experience with the tax obligations of running a business. "To comply with tax laws, these microentrepreneurs [his term for gig economy workers] will be spending relatively large amounts on return preparation assistance and devoting large hours to record keeping."

Gig economy platforms offer some help, but, as the title suggests, independent contractors are mostly on their own. Airbnb commissioned Earnst and Young, a major accounting firm, to put together a 28-page tax guidance pamphlet that was distributed earlier this year to all hosts—i.e., those offering short-term room or home rentals through the site. It's hardly meant to be comprehensive. "Readers are encouraged to consult with professional advisors for advice concerning specific matters before making any decision," the booklet warns on one of the first pages. Still, it's better than nothing, assuming hosts take the time to read it.

There's no getting around the fact that the real problem is an outdated, overly complex tax code.

Sometimes, that works in favor of gig economy workers. Take the somewhat infamous "Masters Exemption," which is credited, perhaps apocryphally, to wealthy residents of Augusta, Georgia, who lobbied Congress in the 1970s to exempt short-term rentals from the tax code so they could continue to rent their houses, tax-free, to the out-of-town visitors who descend on the small community each April for the Masters golf tournament. Some rentals in Augusta can cost as much as $20,000 total over the fortnight of golf-related festivities surrounding the four-day-long tournament.

Though Section 280A(g) was written long before the concept of home-sharing came along, it effectively allows Airbnb hosts who rent their property for less than 15 days annually to avoid paying taxes on that income.

That's one notable exception, though, in a tax code that does little to help workers in the gig economy. Instead of more loopholes, Congress has an opportunity this year to make things easier for everyone.

"Tax reform's promise of simplifying taxes is critical for sharing economy providers," says Romina Boccia, deputy director of the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies, which is housed within the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C. "The current tax code is far too complex, especially on the business side." Workers in the gig economy find themselves become entrepreneurs overnight, and doing their taxes suddenly becomes "a daunting task."

One easy change, says Boccia, would involve that 14-day exemption for rented homes.

Aside from being a giveaway to homeowners within driving range of Augusta National, the idea behind the loophole makes some sense. In theory, the potential tax liability from a home rented for less than two weeks would be almost nonexistent after the host deducts expenses and depreciates the value of the house.

Of course, there's an inherent problem when so-called "safe harbor" provisions are based on the number of days a home is rented. That loophole is a lot bigger when applied to a mansion during the Masters than when applied to a one-bedroom apartment listed on Airbnb. That's why Congress should alter the safe harbor for rental properties so it's based not on the length of time it's occupied for but, more sensibly, on the income that's generated, Boccia says.

IV.

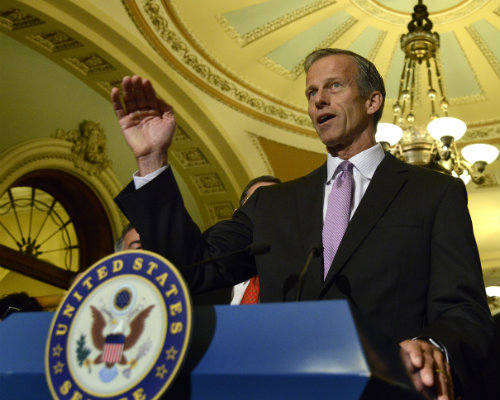

Lawmakers have already begun to propose changes targeted at sharing economy workers. In the Senate, John Thune (R–S.D.), has introduced a bill to make a series of changes to how independent contractors and gig economy platforms fit into the tax code.

Among other things, Thune's bill would settle a long-running dispute over whether Uber drivers and other gig economy workers should be classified as employees or contractors. Lawsuits launched in California last year by a group of Uber drivers attempted to force the company to treat drivers as employees—potentially giving them access to income tax withholding along with health care and other benefits, but also potentially increasing overhead costs for Uber and risking the entire ride-sharing business model.

Thune's bill clarifies that gig economy workers are independent contractors, and that neither service recipients nor third party apps are employers. At the same time, the bill would require gig economy businesses to withhold income tax from their contractors—a provision that would ease the confusion facing Uber drivers who expect income tax to be taken out of their pay in the same way that it is for W-2 employees.

Thune also wants to streamline the tax code by doing away with the inconsistent rules for income reported on a 1099-MISC vs. a 1099-K. Instead of a $20,000 threshold for one type of income and a $600 threshold for the other, Thune proposes a $1,000 reporting threshold for all miscellaneous income, whether paid via credit card or not. He says his bill "would provide clear rules so these freelance-style workers can work as independent contractors with the peace of mind that their tax status will be respected by the IRS."

Sharing economy companies, however, have withheld judgment on the bill so far. "While we're evaluating this proposal, we have always made it clear to every Airbnb host that they must pay taxes," says Nick Papas, a spokesman for Airbnb. "We regularly communicate with our hosts to remind them about tax rules and have a dedicated section on our website where hosts can get all the information they need to meet their obligations." Lyft and Uber did not return requests for comment on Thune's bill.

Though it's unlikely to pass on its own, Thune's New Economy Works to Guarantee Independence and Growth Act—the NEW GIG Act—could get incorporated into an omnibus tax bill if Congress moves one. In the House, Rep. David Schweiker (R–Ariz.) has proposed a bill to allow gig economy platforms to offer income tax withholding without jeopardizing workers' status as independent contractors.

"Tax reform's promise of simplifying taxes is critical for sharing economy providers. The current tax code is far too complex, especially on the business side."

Tax experts say these proposal aren't without their own complications, however. Making withholding mandatory, as Thune's proposal would, is a red flag for Boccia, even though she says offering withholding would help many gig economy workers. "This safe harbor should be created without extortion," she warns. "Companies like Airbnb and Uber should have the option to voluntarily withhold taxes on amounts paid to sharing economy workers, but this should not be a requirement in order to receive clarity regarding worker classification."

Another possible concern is the income reporting threshold, which would be set at $1,000 in Thune's bill. Eliminating the two conflicting levels could reduce confusion, but lowering the $20,000 line for credit card income would also pull more workers into the system. Since the average Uber driver makes about $7,500 annually, and the average Airbnb host makes only slightly more, setting the threshold above that total would allow the majority of gig economy workers—most of whom just do it as a side hustle—to avoid much of the fuss created by the current tax code.

Meanwhile, workers falling above the new threshold—say, $10,000 or so—would be able to take advantage of voluntary income tax withholding to ease their own tax season complexities, if they wanted.

V.

Today, there are more than 2.5 million Americans earning income each month by renting rooms, giving rides, running errands, and selling goods via online, on-demand platforms, according to data collected by JPMorgan Chase. Harvard University researchers found a 66 percent increase in what they called "alternative work arrangements"—including temp workers, on-call workers, independent contractors, and freelancers—from 14.2 million in 2005 to 23.6 million in 2015. The number likely has increased in the two years since, with more online platforms constantly appearing on the scene.

The Aspen Institute estimates that 45 million Americans (or 22 percent of the adult population) have offered some good or service at some point via the sharing economy. And it's not going away. "The rise of 1099 Nation is a structural shift driven by economics, policy, technology and cultural forces—it is unlikely to reverse in our lifetime," says Schütte "Growth in 1099 workers will not halt in the face of regulatory scrutiny, though the way contractors are sourced, hired, and engaged will certainly evolve."

To be sure, this is a small part of the complicated political balancing act that is tax reform. Lawmakers have to worry about how business will respond to corporate tax changes, balance investment income against earned income while deciding how each type of money should be taxed, and figure out what counts as a "fair share."

It might not happen at all. The Trump administration has said that a tax overhaul is a priority, but it has yet to offer a specific plan, and administration officials now say legislation may not pass by the end of the year. That would leave many American workers stuck in a system designed long before their current jobs ever existed.

"Millions of American taxpayers are needlessly burdened by trying to comply with an antiquated, outdated tax system," Bruckner told members of the House Small Business Committee during a May 2016 hearing. "Inaction has very real implications on the Treasury and the IRS' ability to fairly and efficiently collect taxes."

Show Comments (28)