The Crucible, Now at a Campus Near You

Play about literal witch hunts should resonate today.

The centennial of the great American playwright Arthur Miller, born in New York on October 17, 1915, has been noted in articles and recognized with commemorative events and editions. For all the tributes, Miller (who died ten years ago) seems more a relic than a living voice on today's cultural scene; his earnest old-style liberal leftism alienates both conservatives and modern-day progressives obsessed with racial and sexual identities. Yet one of his most famous works, The Crucible—a mostly fact-based dramatic account of the 17th century Salem witch trials—is startlingly relevant to today's culture wars, in ways that Miller himself might have recognized.

Everyone knows that Miller's 1952 play was his response to McCarthyism, with the witchcraft hysteria an allegory for the anti-communist panic. (The latter, unlike the former, was grounded in a real danger; but, contrary to some recent claims on the right, McCarthyite paranoia that swept up many innocent people in its wide net was quite real as well.) In 1996, when Miller wrote a screenplay adaptation for the film version of The Crucible, many saw a metaphor for the day-care sexual abuse panic that had swept the country a few years earlier, with men and women arrested on suspicion of lurid acts and Satanic rituals.

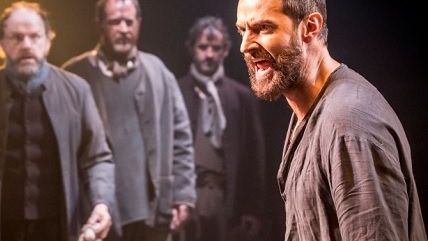

When I recently watched a webcast of the compelling 2014 production of The Crucible at London's Old Vic theater, I was struck by the parallels to another panic we are witnessing now: the one over "rape culture" and, in particular, the "campus rape epidemic."

"Believe the victim"—the mantra of today's feminist anti-rape movement—is a remarkably prominent theme in Miller's play. At one point, Deputy Governor Danforth, who presides over the trials, notes that unlike "an ordinary crime," witchcraft is by its nature invisible: "Therefore, who may possibly be witness to it? The witch and the victim. None other. Now we cannot hope the witch will accuse herself; granted? Therefore, we must rely upon her victims—and they do testify." Today, advocates for "survivors" of sexual violence argue that since such crimes virtually always take place in private, especially when victim and offender know each other, it is imperative to believe those who come forward with accusations.

Of course, "believe the children" was also the mantra of the child abuse trials of the 1980s and early 1990s. But in those cases, the children themselves were a somewhat passive presence, more victims of adult manipulation than active accusers. Not so the girls of The Crucible, whom Miller made older than their 10- and 11-year-old historical counterparts—more young women than children. (Danforth and other adult authority figures in the play often refer to them as "children"; but today's anti-rape advocates, too, often use language that infantilizes young people and young women in particular, sometimes explicitly insisting that college "kids" are not really adults.)

When the Salem girls' veracity is questioned and Danforth asks their ringleader, Abigail Williams, if her visions could be false, Abby responds with self-righteous outrage: "Why, this—this—is a base question, sir. I have been hurt, Mr. Danforth; I have seen my blood runnin' out! I have been near to murdered every day because I done my duty pointing out the Devil's people—and this is my reward? To be mistrusted, denied, questioned…" As Danforth backs down, assuring Abigail that he doesn't mistrust her, she warns, "Let you beware, Mr. Danforth. Think you to be so mighty that the power of Hell may not turn your wits?"

The McCarthy era has no direct parallels to this fetishizing of victimhood or this demand for absolute trust in accusations. But there are uncanny echoes here of today's crusading "survivors" who cry "victim-blaming" when questioned and lament that mistrust retraumatizes and silences victims of sexual assault. "If we use proof in rape cases, we fall into the patterns of rape deniers," Emma Sulkowicz, Columbia University's "mattress girl" and a leader in this crusade, said at Brown University last April.

In Miller's Salem, to question reports of witchcraft was to be suspected of doubting the Bible or even serving the devil. In American universities in 2015, accusations of "rape denialism" are almost as intimidating, even to high-level officials. ("Almost" because on today's campus, no one risks hanging—except maybe in effigy.) A modern-day Abigail would pointedly remind a modern-day Danforth of his "privilege" and warn him of the peril of perpetuating "rape culture."

The girls of The Crucible are a terrifying group, as Yael Farber's Old Vic production starkly conveys. They burn with icy conviction, whipping themselves into fits of agony supposedly inflicted by witches and spirits. (More parallels to the histrionics of the campus activists, so "triggered" by dissent that they have crippling flashbacks, flee to "therapy rooms," and become physically ill.) They easily overwhelm one girl who tries to break away.

There is the obvious caveat that witchcraft does not exist, while rape is all too real. None of the Salem girls were actual victims of witches—though, as the play suggests, many probably came to believe they were. Many anti-rape activists are undoubtedly actual victims of sexual assault. But a "rape culture" in 21st century America is no more real than the devil in the 17th century colonies. And some of today's most visible "survivors"—Sulkowicz, Lena Sclove, Laura Dunn, Lena Dunham—have stories that don't hold up well under scrutiny, or use absurd definitions of rape that equate repeated advances or drunken trysts with forced sex. Some, like the Salem girls, are probably fake victims so caught up in collective zealotry that they believe in their own stories.

To see The Crucible as a parable for the campus anti-rape crusade raises the touchy issue of false accusations as vengeance for sexual rejection. The play's Abby Williams is motivated largely by her past affair (entirely Miller's invention) with her ex-employer John Proctor, vengeance toward his wife Elizabeth, and then anger at Proctor himself for rejecting her. This has caused some feminist scholars to accuse Miller of covert misogyny.

The vindictive scorned woman is indeed a misogynist stereotype. But that doesn't negate the fact that some women, like some men, seek revenge when rejected—and that accusations of abhorrent crimes can be a form of revenge. (The wrong of stereotypes is in generalizing to an entire group.) It could have been true in Salem; it can also be true on today's campus, especially in a climate where women are often encouraged to reinterpret past sexual encounters as nonconsensual. In one recent case at Washington and Lee University, a student was expelled on a charge of sexual assault stemming from an encounter that his accuser admitted she initially saw as consensual and enjoyable. It was only after learning that the young man was seeing someone else—and after spending a summer working at a women's clinic which dealt with sexual violence—that she concluded she had been too drunk to consent.

In his 1996 essay on The Crucible and its themes, Miller wrote that, whatever the setting, "the play evokes a lethal brew of illicit sexuality, fear of the supernatural, and political manipulation." Replace "fear of the supernatural" with "fear of the hidden demons of patriarchal oppression," and you have today's American campus. Perhaps the Miller centennial, and The Crucible's return to Broadway next February, will hasten the much-needed rethinking of the modern witch-hunts.

Show Comments (37)