The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Frederick Douglass Praises the "Courage" Of Justice John Marshall Harlan

“In these easy going days [Harlan] should find himself possessed of the courage to resist the temptation to go with the multitude”

On Tuesday, I spoke at the Louisville Federalist Society Chapter about presidential immunity. After the debate, I was fortunate enough to visit the Library's special collections. The collection includes papers from Justice Louis Brandeis, the namesake of the law school, who is actually buried outside the building. The collection also includes papers from Justice John Marshall Harlan I. I have spent some time with Justice Harlan's papers at the Library of Congress. In 2013, I published a paper with Brian Frye and Michael McCloskey that transcribed Harlan's constitutional law lecture notes. (To this day, I use some of Harlan's lines in class--for example, when I tell my students that the Supremacy Clause is the most important provision in the Constitution; without it, everything else would fall apart.) Over the years, I've corresponded with Peter Scott Campbell, a librarian at Louisville. Campbell was kind enough to show me around the room.

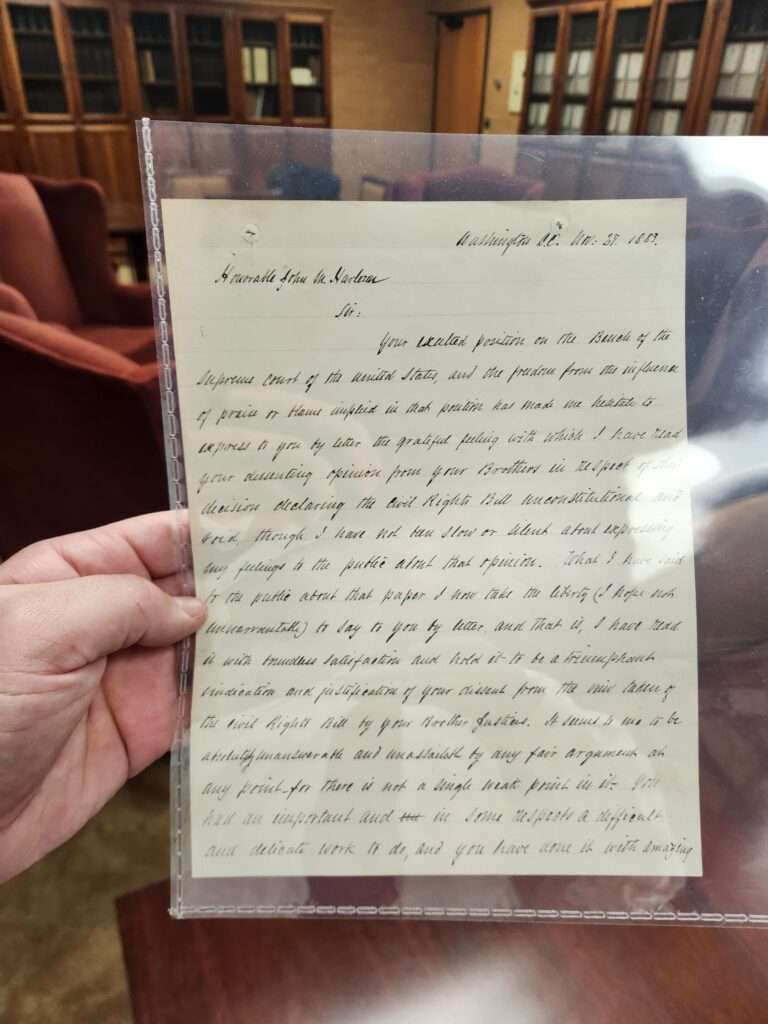

One of the coolest pieces I saw was a letter that Frederick Douglass wrote to Justice Harlan shortly after the Civil Rights Cases (1883) was decided. I encourage you to read the entire letter, which Campbell helpfully transcribed. Here is an excerpt:

[Harlan's dissent] seems to me to be absolutely unanswerable and unassailable by any fair argument at any point for there is not a single weak point in it. You had an important and in some respects a difficult and delicate work to do, and you have done it with amazing ability skill and effect. . . . I have nothing bitter to say of your Brothers on the Supreme Bench, though I am amazed and distressed by what they have done. How they could at this day and in view of the past commit themselves and the country to such a surrender of National dignity and duty, I am unable to explain. I have read what they have said, and find no solid ground in it. Superficial and [???], smooth and logical within the narrow circumference beyond which they do not venture, that is all.

To this day, I remain convinced that Justice Harlan was correct in the Civil Rights Cases. Had his view prevailed, the Court would have never needed to contort the Commerce Clause is Katzenbach and Heart of Atlanta Motel. And cases like United States v. Morrison would have come out differently. Moreover, if the Civil Rights Act of 1875 had been upheld, we never would have had Plessy, because a segregation law on a public conveyance would have been preempted by the federal bill. Everyone focuses on Plessy, but truly the root cause of the problem was The Civil Rights Cases, and if you want to go back a decade earlier, The Slaughter-House Cases.

Douglass also included an article he wrote in The American Reformer newspaper about Harlan's dissent. The first paragraph defends Harlan's decision on its own terms:

[Harlan] has felt himself called upon to isolate himself from his brothers on the Supreme Bench, and to place himself before the country as the true expounder of the Constitution as amended, and of the duty of the National Government to protect and defend the rights of citizens against any infringement of their liberty. The opinion which he has given to the country, as to the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Bill, places his name among the ablest jurists who have occupied the Supreme Court. No utterance from that Bench, since the celebrated and splendid opinion given by Judge Curtis against Judge Taney's infamous Dred Scott decision, has equaled this opinion in ability, thoroughness, comprehensiveness and conclusive reasoning. Compared with it the decision of the eight judges was an egg shell to a cannon ball. We are told in Scripture that one shall chase a thousand, but one opinion like this could put to flight ten thousand of such decisions as the thin, gaunt and hungry one which denies the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Bill, and the duty of the Federal Government to protect the rights and liberties of its own citizens. No man, unless blinded by passion, prejudice, or selfishness, can read this opinion without respect and admiration for the man behind it. Where the decision of the Court is narrow, superficial and technical, the opinion of Judge Harlan is broad and generous, and grapples with substance rather than shadow, with things as they are rather than with abstractions…

A few important points jump out here. First, Douglass twice refers to the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as "protecting the rights and liberties" of citizens. This is precisely the correct accounting of the Fourteenth Amendment. Section 1 made the freedmen citizens, and granted them the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The states then had a duty to equally protect those privileges and immunities, which included the right to access places of public accommodation. And Congress, through Section 5, could enact appropriate legislation to ensure those rights were protected. The Equal Protection Clause was not, as the Warren Court would tell you, about treating everyone equally. Instead, Douglass's conception is how Chris Green explains it: the Equal Protection Clause imposes a duty to protect everyone equally from the violation of rights. Douglass was able to articulate sophisticated constitutional principles in so few words.

Second, Douglass pays homage to Justice Curtis's dissent in Dred Scott. It is not well known, but Curtis resigned from the Supreme Court shortly after Chief Justice Taney's decision. Curtis was held in high esteem by Douglass, and Harlan entered that pantheon. I would wager that Justice Story, author of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, would not make the cut.

Third, Douglass uses the phrase "grapples with substance rather than shadow." This phrase may sound familiar. Chief Justice Roberts used the same phrase in the Trump immunity decision:

That proposal threatens to eviscerate the immunity we have recognized. It would permit a prosecutor to do indirectly what he cannot do directly—invite the jury to examine acts for which a President is immune from prosecution to nonetheless prove his liability on any charge. But "[t]he Constitution deals with substance, not shadows." Cummings v. Missouri, 4 Wall. 277, 325 (1867).

Another passage from Douglass is particularly significant in light of recent discussions on this blog:

As to Justice M. Harlan, no man in America at this moment occupies a more enviable position. His attitude is one of marked moral sublimity. The marvel is that, born in a slave State, as he was, and accustomed to see the colored man degraded, oppressed and enslaved, and the white man exalted; surrounded by the peculiar moral vapor inseparable from the slave system, he should so clearly comprehend the lessons of the late war and the principles of reconstruction, and, above all, that in these easy going days he should find himself possessed of the courage to resist the temptation to go with the multitude. He has chosen to discharge a difficult and delicate duty, and he has done it with great fidelity, skill and effect. In other days, when Garrison, Phillips, Sumner, Wilson and others spoke, wrote and moved among men, Old Massachusetts did not leave to Kentucky the honor of supplying the Supreme Bench with a moral hero. That State then spoke through the cultivated and legal mind of Judge Curtis. Happily for us, however, Kentucky has not only supplied the needed strength and courage to stem the current of pro-slavery reaction, but she has also supplied in Justice Harlan patience, wisdom, industry and legal ability, as well as heroic courage.

I've written at some length about the concept of judicial courage. And I cite a lack of courage to explain why some judges vote the way they do. Will, Orin, and Sam recoil at my discussion of judicial "courage." They think it is a corrosive and dangerous way of thinking about judges. They also think it problematic to focus on how a judge votes, rather than substance of their opinions.

This latter point would come as a surprise to entire political science departments that painstakingly count how Justices vote. And I assure you, my "courage" analysis is not new. It goes at least back to Douglass, and really much earlier. Judges today, judges in the twentieth century, and judges in the nineteenth century, are not much different. There is always the "temptation" to, as Douglass writes, "go with the multitude." Now you might try to localize "courage" to standing up to racism and Jim Crow. But that was not Douglass's argument at all. Rather, courage means a willingness to stand alone for your principles, and to go out on your own. Lone dissents take courage. Justice Thomas issues them without any concern. Justice Alito has issued a few over time. Justice Scalia's Morrison dissent comes to mind. How often are the other Justices willing to stand alone, and buck the trend of the "multitudes"?

On a related point, I have some other archival documents from Justice Brennan's papers in which he thanks and praises a Supreme Court advocate, who is still with us, for his defense of the Court. I'll publish those at the appropriate time. There is nothing new under the sun.

Show Comments (16)