The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

About Justice Jackson's "Recusal" From Loper Bright

Justice Jackson's "participation" in Relentless and SFFA further demonstrates why the usual recusal rules will not work for the Supreme Court.

Last term, the Supreme Court decided two affirmative action cases brought by Students for Fair Admission. Justice Jackson was recused from the Harvard case, since she served on the Harvard Board of Overseers. But Jackson participated in the University of North Carolina case. Ultimately, the Court only issued a single decision. Everyone can reasonably assume that Justice Jackson reviewed portions of the draft that concerned the Harvard case, even if she signaled that she didn't actually participate in that case.

Richard Re criticized Jackson. I defended Jackson. I contended that the "duty to sit" on the Supreme Court is significant, and should not be discarded lightly--even where some people may see a potential conflict of interest. Moreover, I surmised that Jackson consulted with her colleagues on how to proceed. Indeed, every Justice signed off on how Jackson characterized her role in the case, and presumably agreed with her decision.

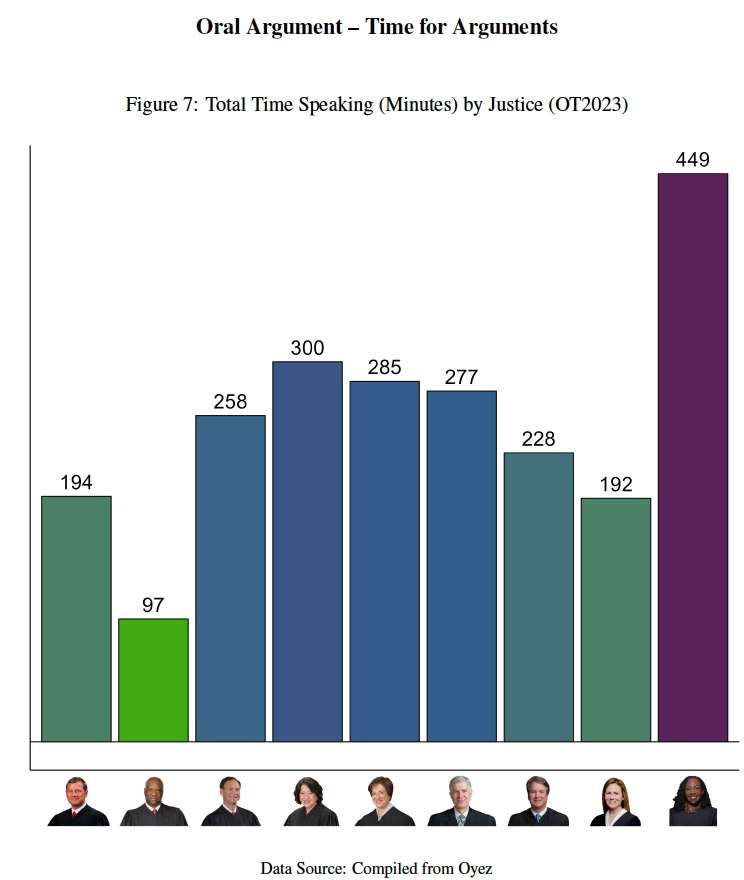

Another term, another "recusal." (Will Baude flagged it here.) The Supreme Court originally granted cert in Loper Bright. Justice Jackson heard oral argument in that case during her ever-so-brief tenure on the D.C. Circuit, but did not issue an opinion in that case. (Justice Thomas jokes that he was on that court for a short period, but at least he made it past the one-year mark.) Despite her limited involvement in the case, Jackson recused from Loper Bright. Later, the Court granted cert in Relentless, a similar case from the First Circuit. The thinking was that this would give Justice Jackson a chance to participate. But unlike the two SFFA cases, where the UNC case had the Fourteenth Amendment issue, the questions presented in Loper Bright and Relentless were identical. This cert grant was designed solely to let KBJ ask questions during oral argument. That's it. The Court heard separate oral argument in each case. And participate Jackson did--according to Empirical SCOTUS she spoke for more than 13 minutes, whereas Justice Sotomayor spoke for about 6 minutes. Here is the breakdown for the whole term:

Fast-forward to the decision. Justice Kagan's dissent includes this footnote:

JUSTICE JACKSON did not participate in the consideration or decision of the case in No. 22–451 and joins this opinion only as it applies to the case in No. 22–1219.

What does that even mean? Both cases were jointly considered. It is a fiction that they could be separated. But I'll defend Jackson again. This is a case of the utmost importance, and the mere fact that she participated in the lower-court opinion really does not require her recusal. I've never fully understood this rule about recusal based on past participation. The Justice does not have to recuse if they had previously ruled on a legal issue in a different case; only in the same case. In 2018 Justice Kennedy was forced to recuse in a case because he participated in an earlier proceeding from 1985 on the Ninth Circuit. In what world does that rule even make sense? Kennedy had forgotten about the case, yet he somehow has some sort of latent bias?

Back in the good old days, Justices who heard a case while riding circuit could would hear the case again when it was appealed to the Supreme Court. My understanding is that Justice Bradley participated in Cruikshank before the District of Louisiana, and there is no indication he recused on that case when it was certified to the Supreme Court. I hope I don't trigger anyone with a discussion of Section 3, but had Jefferson Davis not been pardoned, Chief Justice Chase would have heard his criminal appeal before the Supreme Court, after presiding over the criminal trial. (I'm sure some moderns will find yet another ethical violation based on ethical rules that did not exist at the time.)

Justice Jackson did nothing wrong. What difference does it make that she heard oral argument? We are often told that questions at oral argument should not be taken as an indication of which way a judge is going to vote. Moreover, hearing Loper Bright as a circuit judge focused on the best reading of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Act. But before the Supreme Court, the only issue was whether Chevron should be overruled--a question that a circuit judge could not even think about. Where is the conflict? I think that these sorts of recusals are largely performative, and not about addressing actual conflicts. As I said last year, there should be fewer Supreme Court recusals, and not more.

Show Comments (15)