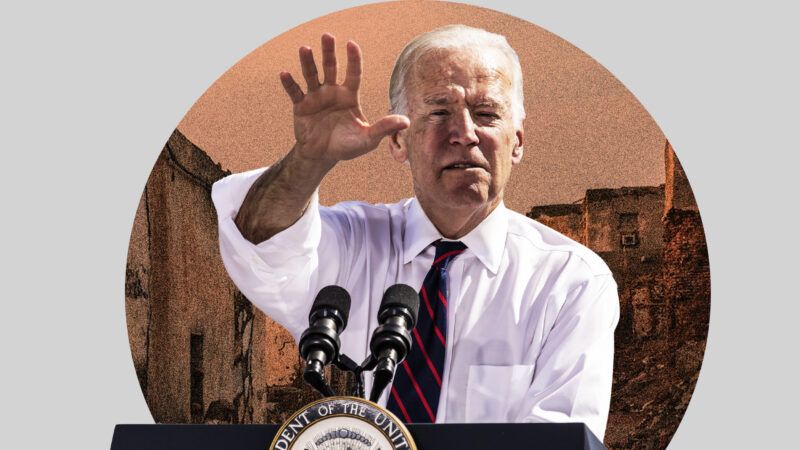

Why Aren't We Out of Yemen Yet?

Biden's vague, partial drawdown isn't enough.

President Joe Biden's announcement two weeks after taking office that he would end "all American support for offensive operations in the war in Yemen, including relevant arms sales," was welcome. It was also inexcusably ambiguous, and when lawmakers sought clarity into the scope of the policy change, the administration mostly declined to give it. Biden's announcement "includes the suspension of two previously notified air-to-ground munitions sales and an ongoing review of other systems," wrote the State Department in a letter. But beyond that, the administration didn't indicate what military support would continue to flow to the Saudi-led coalition intervening in Yemen's grueling civil war.

An extensive new report from The Washington Post this week confirms that skepticism of the drawdown was warranted and the specification of "offensive operations" was deceptive. While rightfully decrying Russian aggression against civilian targets in Ukraine, the U.S. government continues to be implicated in the same kind of brutality against civilians in Yemen, the site of the world's most acute humanitarian crisis. This Post report is fresh evidence that we need to know exactly how the U.S. government is backing the Saudi-led coalition and its war crimes in Yemen—and that this backing needs to stop.

The Post story is not the first to suggest that U.S. involvement in Yemen continues to be significant. We already knew, for instance, that other weapons deals had proceeded during Biden's tenure. The president and Congress signed off on a $650 million sale of missiles and other arms to Saudi Arabia in late 2021, and the State Department approved millions more in February—using language of rationale copied and pasted from a Trump administration sale completed before Biden's ostensible policy change, Responsible Statecraft reports.

We also knew the administration had yet to cancel military maintenance contracts which, per the Post article and previous reporting by Vox, are crucial for continuing airstrikes in Yemen. "If we don't sell [Saudi Arabia a] particular ammunition, they can still fly. They have got a lot of munitions stockpiled. They might be able to find replacements," Rep. Tom Malinowski (D–N.J.) told the Post. "But there's no replacement for the maintenance contract and no ability to fly without it." These "contracts fulfilled by both the U.S. military and U.S. companies to coalition squadrons carrying out offensive missions have continued" since the "offensive operations" announcement, the Post found, even though the air campaign is responsible for most direct civilian deaths and Biden couched his comments in concern for civilians.

And we knew that the Biden administration had not pushed for an immediate end to the Saudi blockade of Yemen, officially intended to intercept Iranian weapons but in practice a major contributing factor to the country's famine conditions and severe shortages of necessities like medicine and fuel. The State Department letter didn't answer lawmakers' inquiry about transfers of naval equipment, which could be used to prolong the blockade, and "the U.S. Navy occasionally announces it has intercepted smuggled weapons from Iran," the Brookings Institution notes, "suggesting a more active role [in the blockade] than the administration admits."

The crucial new information of the Post report, then, is the identification "for the first time [of the] 19 fighter jet squadrons that took part in the Saudi-led air campaign in Yemen." While the Pentagon had claimed it could not reliably distinguish which units were engaged in the precluded offensive operations, the Post investigation was able to do exactly that. It was also able to determine that the U.S. military conducted training exercises, some of them on U.S. soil, "with at least 80 percent of [coalition] squadrons that flew airstrike missions in Yemen." These continued after Biden claimed to end offensive operations support. A round of training in March 2022, for example, would "concentrate on three primary themes," said an Air Force write-up. One of them was "offensive" techniques.

These revelations come, on several counts, at an opportune moment for U.S. policy to change course. The United Nations last week announced a two-month extension of a truce begun in April, the first such nationwide ceasefire since the civil war began in 2014. This truce is not only an immediate relief for Yemeni civilians but also an important step toward a negotiated peace, one which suggests even the partial U.S. drawdown may be having some effect on the coalition's appetite to continue the war.

Here in the States, a bipartisan resolution introduced in the House this month would direct the president to more comprehensively end "U.S. military participation in offensive air strikes," including—particularly in light of the Post's squadron identifications—canceling maintenance contracts.

Meanwhile, Biden is reportedly considering a trip to Saudi Arabia in July. He's been widely castigated for the plan, which would mark a major reversal of campaign-era talk about making the regime a "pariah." But the visit has yet to be formally announced, which means Biden could still cancel or reconfigure it to push the Saudi government toward a more permanent peace in Yemen.

The president doesn't need to wait for Congress to pass that resolution to wind down U.S. military support for the coalition; constitutional constraints on presidential war powers are all on the side of joining wars, not leaving them. Nor does Biden need congressional permission to give the American people full information on what our government has done in Yemen and how it can—and should—stop working with the Saudi-led coalition going forward. He can speak plainly to the public and Riyadh whenever he likes.

We've had weasel words enough about the U.S. role in Yemen for three presidencies now. It's time for transparency—and peace.

Show Comments (58)