California, New York Have the Most To Gain From Ending Bonus Unemployment Benefits. They Probably Won't.

States that already had lower unemployment rates in May are more likely to have announced plans for ending the bonus unemployment payments.

Consider this your periodic reminder that economic incentives matter: Available job postings appear to be getting filled more quickly in states that are paying fewer benefits to people who are unemployed.

There's a real-life economic experiment happening across America right now, as 26 states have taken steps to limit or eliminate the $300 per week "bonus" unemployment benefits that are paid by the federal government and layered atop whatever state-level benefits unemployed workers receive. Those federally boosted unemployment benefits—a temporary measure enacted due to the COVID-19 pandemic—are set to expire in September.

But some states are doing away with them before that deadline in hopes of spurring a faster labor market recovery. In the states that were quickest to cut off the bonus unemployment payments, The Wall Street Journal reports, that strategy seems to be working out.

"The number of workers paid benefits through regular state programs fell 13.8 percent by the week ended June 12 from mid-May—when many governors announced changes—in states saying that benefits would end in June, according to an analysis by Jefferies LLC economists," the Journal reports. "That compares with a 10 percent decline in states ending benefits in July, and a 5.7 percent decrease in states ending benefits in September."

There are more than 9 million jobs available across the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' most recent update. There's also widespread anecdotal evidence that employers are having a hard time finding workers to fill open positions. "America's great economic resurgence is being held back by an unprecedented workforce shortage—and it's getting worse," says Neil Bradley, executive vice president and chief policy officer for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

But the degree to which temporary federal unemployment benefits are contributing to this situation remains subject to debate. In fact, The New York Times published a piece on Sunday that drew almost the exact opposite conclusions as the Journal's article did. After suspending the extra $300 per week jobless benefits on June 12, Missouri employers expected to see "a flood of job-seekers" but were left disappointed, the Times claims.

It's probably true that the bonus federal unemployment benefits are not solely to blame for the labor market's slow recovery right now. But they are almost certainly contributing to the situation.

Potential workers who aren't reentering available jobs "could be caring for family due to pandemic restrictions on in-person schooling, enjoying an early retirement, or waiting for the right job to open up," Michael D. Farren, a research fellow for the Mercatus Center, a free market think tank, wrote earlier this month here at Reason. But those other factors seem to account for only a small share of the declining workforce, Farren concluded, leaving "the federal expansion of unemployment insurance as a major driver of workers' decisions to remain on the sidelines."

Other economic studies suggest the same. A 2014 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis that examined the effects of extended unemployment benefits during and after the 2008 economic crisis found that "longer benefits may reduce unemployed workers' job search efforts, decreasing their likelihood of becoming reemployed." The circumstances now are slightly different, but the decision to extend those bonus federal unemployment benefits all the way until September—a decision that federal policymakers made in March, when it was clear the pandemic was coming under control and the economy was recovering—almost certainly had an impact on some would-be workers' economic incentives.

The shifts in unemployment benefits have become something of a Rorschach test because we don't yet have any empirical data regarding how unemployment rates shifted in the wake of various states cutting off those bonus benefits. The four states that led the way in cutting off the $300 per week federal unemployment bonus didn't do so until June 12, and the most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics data on state-level unemployment is from May. June's data won't be released for another few weeks.

But here's one thing we can say with certainty: The states that have the most to gain from cutting off extra benefits in the hopes of nudging workers back into available jobs are, for the most part, not doing that.

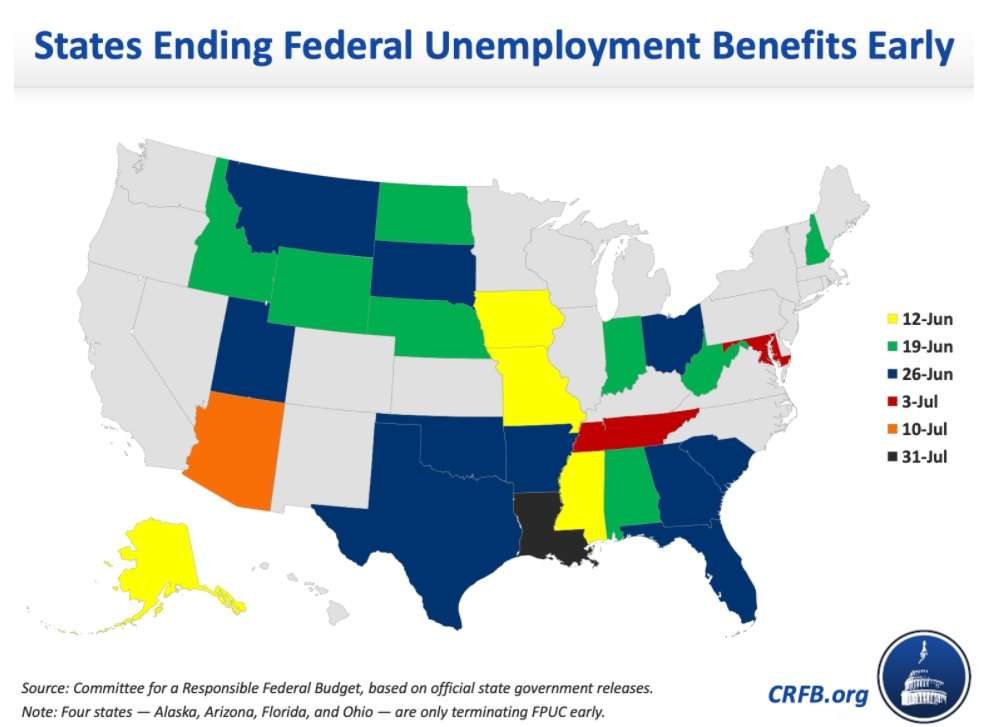

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) has been tracking which states are ending the boosted federal unemployment benefits, as well as when the added payments will terminate. Here's their most recent update on the 26 states that have terminated or announced plans to terminate the $300 federal benefits boost.

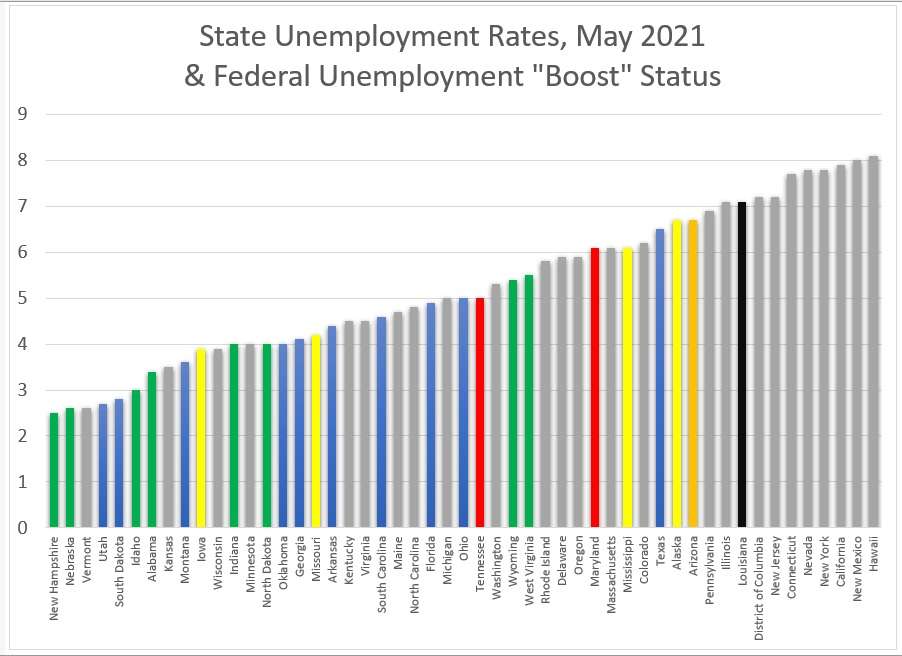

Here's how it looks when that same information—color-coded in the same way—is arranged to show the states ranked by their respective unemployment rates.

It's far from a perfect correlation, of course, but there's a clear trend here. States that already had lower unemployment rates in May are more likely to have announced plans for ending the bonus unemployment payments in June or July. We'll have to wait a bit to see how that changes this distribution, but it seems likely to only deepen the divide between places that are emerging from the pandemic with healthy economies and those that are lagging behind.

But this is also something of a chicken-or-egg problem. When the Times goes spelunking into Missouri to find that there hasn't been a "flood" of new job-seekers since the policy change two weeks ago, maybe it is only identifying the fact that unemployment in Missouri was already about half as high as it is in, say, New York.

This is an ongoing experiment so it's probably not fair to draw any serious conclusions just yet. But if New York or California announced plans to cut off that bonus $300 per week federal unemployment boost before September, it seems likely that the results would be more dramatic than what's happening elsewhere.