Ideas Aren't Enough—Freedom Needs Good Stories

Good stories introduce people to liberty long before they think about policy.

Having spent most of my career engaged in political debate—as a writer, teacher, organizer, and think tank president—I'd like nothing better than to counter the grave threats currently facing American liberty with the standard tools of public policy.

Are politicians meddling more and more in markets? Then let's publish rigorous empirical research, powerfully written books, and attention-grabbing articles to convince them of their folly. Is the progressive quest for equity threatening equality under the law? Then let's explain, patiently and persuasively, how such goals are best accomplished by eliminating barriers and embracing individualism rather than redistribution and collectivism. Are professors and students being "cancelled" for expressing impolitic ideas? Then let's strengthen First Amendment protections on campus. Is the practice of American government increasingly at odds with the principles of federalism, separation of powers, and the rule of law? Then let's pass new laws or constitutional amendments to restore the ideals of the American Founding.

The strategy is familiar and inviting. It fits like a comfortable shoe. I'd like to believe it would kick the ball hard enough to score a goal, but experience has convinced me otherwise. While such activities are necessary to the defense of classical liberalism, they fall far short of being sufficient.

Most Americans don't think about politics and government very much. For the most part, that's a trait worth celebrating. Their daily lives aren't consumed with legislative procedure or partisan bickering. They vote but they don't obsess about it. They answer poll questions about specific policies, but their answers are often more artificial than insightful, reflecting more the choice of terms and limited range of options presented than what they really think. Even within the political class—by which I mean not just elected officials but also the people who staff their offices, run and fund their campaigns, and try to sway their decisions—abstract concepts and abstruse arguments fail to explain much of what people say and do.

Ideas do have consequences. But those consequences are contingent on factors beyond the substance and soundness of the ideas themselves. They depend on context, on timeliness, on presentation. Among elites and masses alike, ideas have the greatest consequences when embedded in narratives.

Human beings aren't calculating machines. We're storytellers. Our facility for language has helped enable learning, planning, cooperation, and exchange, propelling our species to success. As my friend and former Duke colleague Frederick Mayer explained his 2014 book Narrative Politics, social and political movements need something more than shared goals and concepts to thrive: They must inspire costly, time-consuming behavior by busy human beings whose default setting is to take no notice or action. "Facts are great, analysis is important, but if the goal is political mobilization, a shared story is essential," Mayer says. "You cannot beat a story without another story. Politics often revolves around a contest of stories."

Champions of liberty have been repeating this wisdom to each other for years. That's why we are quicker to spotlight a particular student harmed by ineffective schools, or a particular professor harmed by speech codes, or a particular entrepreneur shackled by regulation, rather than just citing empirical studies or presenting philosophical arguments.

But even case studies and anecdotal leads are insufficient. Ideas assume tremendous narrative power when expressed in novels, shows, films, and art. "All stories are fictions," Mayer observes, "yet some fictions are essentially true."

There may be no truer description of government tyranny than the scene in Robert Heinlein's The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress when the protagonist, Mannie, reflects on what he and other residents of Luna left behind on Earth: "Do this. Don't do that. Stay back in line. Where's tax receipt? Fill out form. Let's see license. Submit six copies. Exit only. No left turn. No right turn. Queue up and pay fine. Take back and get stamped. Drop dead—but first get permit."

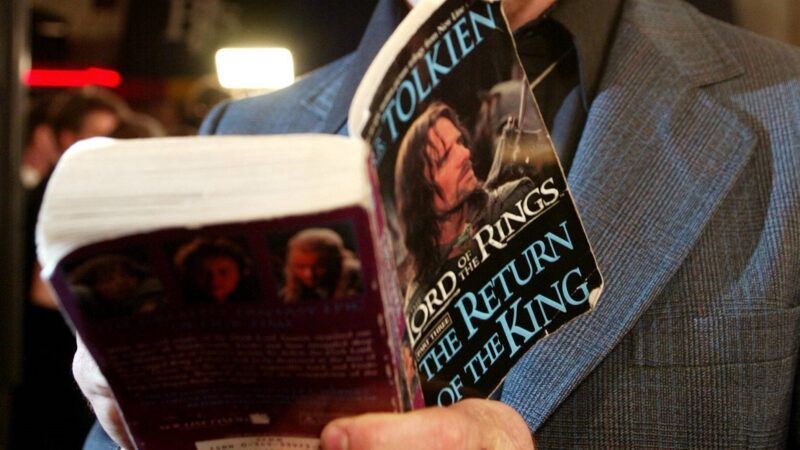

Generations of young people gained their deepest understanding of totalitarianism not from lectures or textbooks about the Soviet Union but by reading George Orwell. Many heard their first full-throated defense of markets and individualism not from economists or historians but from Ayn Rand's characters. And for many, their first introduction to the seductions of power—and to the qualities it takes to resist them—came from watching the hobbit Sam become a ringbearer in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Return of the King: "Already the Ring tempted him, gnawing at his will and reason. Wild fantasies arose in his mind; and he saw Samwise the Strong, Hero of the Age, striding with a flaming sword across the darkened land, and armies flocking to his call as he marched to the overthrow of Barad-dûr. And then all the clouds rolled away, and the white sun shone, and at his command the vale of Gorgoroth became a garden of flowers and trees and brought forth fruit. He had only to put on the Ring and claim it for his own, and all this could be." But "deep down in him lived still unconquered his plain hobbit-sense: he knew in the core of his heart that he was not large enough to bear such a burden, even if such visions were not a mere cheat to betray him. The one small garden of a free gardener was all his need and due, not a garden swollen to a realm; his own hands to use, not the hands of others to command."

Young (and not-so-young) readers also encountered a key passage about the abuse of power in The Magician's Nephew, by Tolkien's friend C.S. Lewis. The nephew in question, Digory, had just called his uncle "rotten" for breaking a promise to trick another character, Polly, into transporting away:

"Rotten?" said Uncle Andrew with a puzzled look. "Oh, I see. You mean that little boys ought to keep their promises. Very true: most right and proper, I'm sure, and I'm very glad you have been taught to do it. But of course you must understand that rules of that sort, however excellent they may be for little boys—and servants—and women—and even people in general, can't possibly be expected to apply to profound students and great thinkers and sages. No, Digory. Men like me, who possess hidden wisdom, are freed from common rules just as we are cut off from common pleasures. Ours, my boy, is a high and lonely destiny."

As he said this he sighed and looked so grave and noble and mysterious that for a second Digory really thought he was saying something rather fine. But then he remembered the ugly look he had seen on his Uncle's face the moment before Polly had vanished: and all at once he saw through Uncle Andrew's grand words. "All it means," he thought to himself, "is that he thinks he can do anything he likes to get anything he wants."

Such classics are still popular today, as are more-recent works by liberty-minded writers and artists. But there aren't nearly enough of them, I would submit, to sustain a rich culture of freedom. Large swaths of today's popular entertainment cast business as the villain, government as the hero, and everyone else as helpless victims. They exalt "social justice" over freedom, expediency over truth, and the collective over the individual. We can and should rebut these calumnies with facts and arguments. But we must also tell many more stories of our own — in print, audio, video, and art. A few may break through to become bestsellers or cultural touchstones. But such an outcome isn't required to accomplish the task. In today's splintered marketplace, producing a large number of works with discrete audiences and themes is likely to be more effective than placing a few big bets and hoping for a blockbuster.

The defense of American liberty and the renewal of American institutions cannot be accomplished without patient capital invested in intellectual infrastructure. I believe in the value of scholarship, policy analysis, journalism, leadership development, and academic programs. But in the "contest of stories" that forms the substance of most political disagreements, lovers of liberty must use all the tools at our disposal.

To quote a character in Mountain Folk, my novel of the Revolutionary War: "Glory is a lonely man. Best marry him to Victory."

Show Comments (59)