RIP Mark Schlefer, the Man Who Made FOIA Happen

"In the drafting, we were adamant that you didn't have to have an interest to have access. You could just be a citizen."

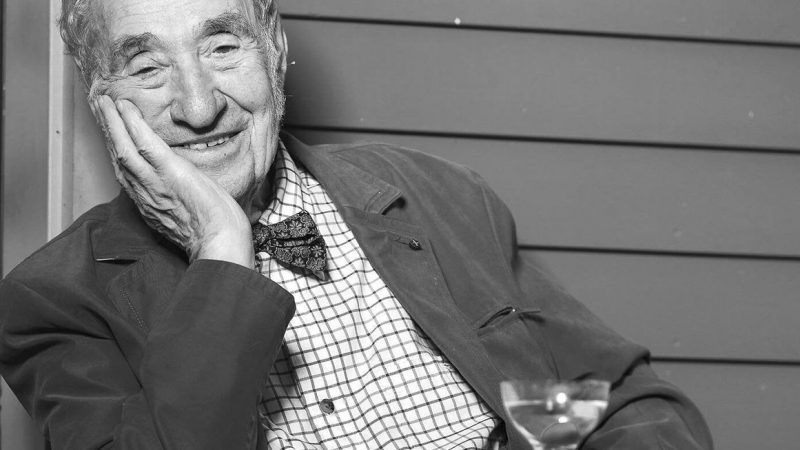

Mark Schlefer, who died in November at age 98 in Vermont, lived a full life that included 36 combat missions on a bomber crew in World War II and starting a fund to provide tuition assistance for minority children at D.C.-area private schools. But he will be best remembered for helping draft the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), a landmark federal law that opened up government records to the public.

In the early 1960s, Schlefer was working as a maritime lawyer on behalf of a shipping company that had been denied tariff documentation by the Federal Maritime Commission to stop at the Mariana Islands. When Schlefer asked for a copy of the legal opinion justifying the decision, he was told it was confidential.

Schlefer couldn't believe that the government's interpretation of the law his client was expected to follow was secret, but he soon learned that he wasn't the only one getting stonewalled. When he brought his problem to the American Bar Association, he learned that two other members of the body were already working with Rep. John Moss (D–Calif.) to draft a transparency bill.

Moss was also working with the American Society of News Editors, which had published an alarming report on government secrecy in 1953. The government's classification system ballooned in the midst of the Cold War, and there was no clear right to see government records and no clear judicial remedy for those who were denied access.

Moss' interest in transparency started after he picked a fight with the Eisenhower administration over records on nearly 3,000 federal employees it had fired for having Communist ties. He had been needling successive administrations over their undue secrecy for nearly a decade when Schlefer walked into his office with a draft of the legislation that would become the Freedom of Information Act.

"I had planned just to leave [the draft] with him, but he asked me to sit," Schlefer later wrote in The Washington Post. "After reading it slowly and carefully, he looked up and said, 'Mr. Schlefer, I'll deliver the House. You deliver the Senate.'"

It was an uphill battle. Twenty-seven federal agencies testified on the proposed legislation, all of them in opposition. The Justice Department argued that the bill was unconstitutional because it would violate the separation of powers. But by 1966, Moss, true to his word, acquired a critical mass of support in the House for FOIA, which passed 307–0. (A young Republican named Donald Rumsfeld, who co-sponsored the bill, would later advise Gerald Ford to veto amendments strengthening FOIA. Congress overrode Ford's veto.)

Schlefer, meanwhile, got the bill in front of the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, where it was shepherded to the floor and eventual passage. President Lyndon B. Johnson privately opposed FOIA. But he was hemmed in by his own party and signed it into law on July 4, 1966, at his Texas ranch.

FOIA established a presumptive right to see government records unless those records qualify for one of nine exemptions. Despite the broad exemptions and lax enforcement of FOIA, it has led to the release of everything from pictures of former Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt's $43,000 phone booth to a collection of interviews with Pentagon brass about the U.S. war in Afghanistan that sharply contradicted what they had told the public.

All 50 states passed their own versions of the law. Freedom of information laws now exist, at least on paper, in more than 100 countries.

Schlefer and others' contributions to FOIA were born out of self-interest but not cynicism or self-promotion. One of the most important features of FOIA is that anyone, not just a lawyer or reporter, has a right to request government documents. "In the drafting, we were adamant that you didn't have to have an interest to have access," Schlefer said in a 2017 interview with Vermont's Bennington Banner. "You could just be a citizen. This was critical."

As tends to happen, the product of this collaboration proved more popular and durable than any of the individuals behind it could have imagined. In fiscal year 2019, the federal government received 858,952 FOIA requests.

Show Comments (12)