Don't Pack the Courts

Joe Biden shouldn't repeat FDR's big mistake.

On February 5, 1937, President Franklin Roosevelt made what would prove to be one of the biggest blunders of his political career. "The personnel of the Federal Judiciary is insufficient to meet the business before them," Roosevelt announced in a special message to Congress. His plan to fix the alleged problem: Pack the courts. "A constant and systematic addition of younger blood will vitalize the courts," FDR declared, "and better equip them to recognize and apply the essential concepts of justice in the light of the needs and the facts of an ever-changing world."

Under the court-packing legislation that Roosevelt sent to Congress, the president would get to appoint one new federal judge for every sitting federal judge that had served at least 10 years on the bench and had failed to retire or resign within six months of reaching the age of 70. In practical terms, the bill would empower Roosevelt to completely reshape the federal judiciary, letting him name up to 44 brand new federal judges and, most important, up to six new Supreme Court justices, bringing the total in that body as high as 15.

The odds of success certainly seemed to be in the president's favor. Not only did Roosevelt's party control both houses of Congress at the time but it did so by an absolutely lopsided legislative majority. In the House of Representatives, the Democrats' advantage was a staggering 4–1. And "the president had so overwhelming a majority in the upper house," the historian William E. Leuchtenburg noted of the Senate, "that several Democrats could find seats only across the aisle in the Republican section."

But then everything started to go wrong. Opposition to the plan rapidly mounted. What is more, the bill's most effective adversaries turned out to be members of Roosevelt's own party, such as the legendary progressive jurist Louis Brandeis, who deftly maneuvered behind the scenes to ensure the bill's ultimate defeat. Like so many others at the time, Brandeis was frankly aghast at FDR's blatant power grab. "Tell your president," Brandeis coldly informed Roosevelt adviser Tom Corcoran after learning of the plan, "he has made a great mistake."

Despite its many perceived advantages—a popular president recently reelected, a friendly Congress full of ostensible allies—the court-packing plan would be dead and buried in less than six months, unceremoniously entombed within the confines of the Senate Judiciary Committee, from which it would never emerge.

Eight decades later, a growing number of Democrats are ready to try again. "Should Democrats win" control of both Congress and the White House, declared New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie in 2019, "they should expand and yes, pack, the Supreme Court….Likewise, expand and pack the entire federal judiciary to neutralize [President Donald] Trump and [Senate Majority Leader Mitch] McConnell's attempt to cement Republican ideological preferences into the constitutional order."

Joe Biden's election to the White House has brought that scenario one step closer. At the time of this writing, the Democrats have a grip on the House of Representatives, while the future of the Senate remains to be decided by a pair of special elections that will be held in Georgia in January. Should the Democrats actually succeed in winning control of the upper chamber at some point in the near future, the arrival of a new court-packing scheme on Capitol Hill is within the realm of possibility.

Historians have long been fascinated by the spectacular failure of FDR's judicial gambit. Given the unruly state of American politics today, the story of how and why his court-packing bill met its demise may hold some potent lessons for the present as well.

'The Judicial Power'

According to Article III, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution, "the judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." The document says nothing about the number of judges needed to fill the bench.

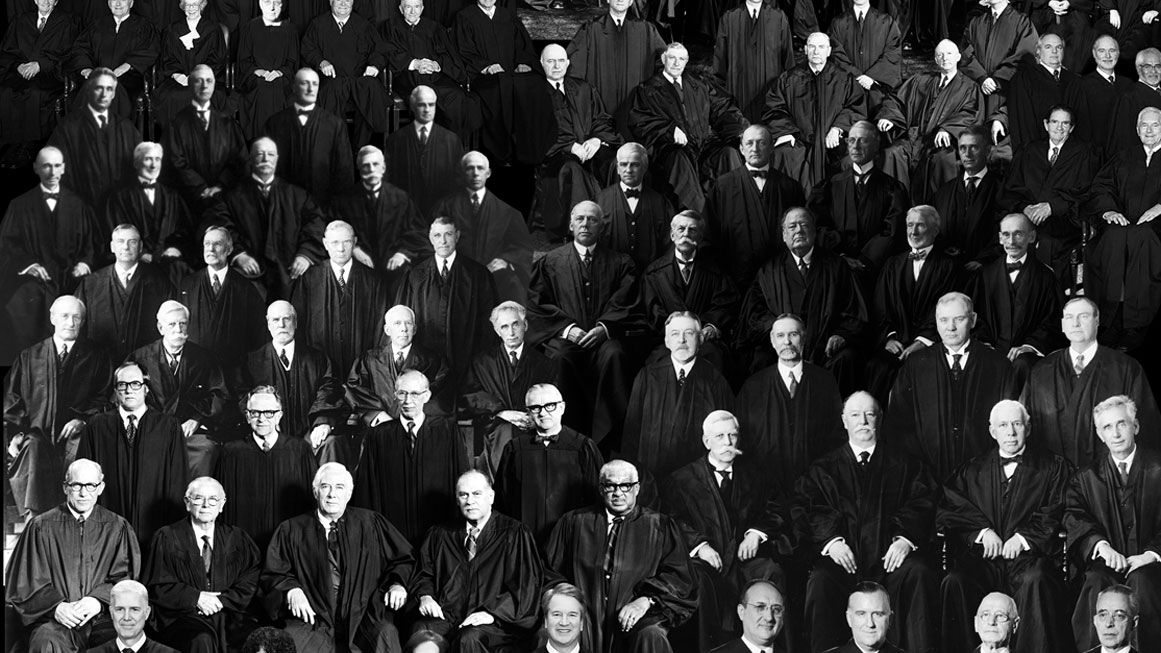

The Judiciary Act of 1789 took care of that, setting the size of the first Supreme Court at six. "Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives," the law read, "that the supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum."

That figure would fluctuate in the years ahead, dropping down to five justices at one point and then climbing to seven at another. The high-water mark came in 1863, when the Supreme Court briefly had 10 justices as a result of Congress expanding the federal bench to include the new U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. The Judiciary Act of 1869 would later fix the number of justices at nine, where it has remained ever since.

Although the idea of tinkering with the size of the Supreme Court for the express purpose of filling it with simpatico jurists is most closely associated with Franklin Roosevelt, the idea was not original to him. His famous older cousin had floated the concept three decades earlier.

In 1912, former president Theodore Roosevelt launched a third-party run for the White House under the Progressive Party banner. Attacks on the "reactionary" Supreme Court played a notable part in his campaign.

The Rough Rider was particularly incensed by decisions such as Lochner v. New York (1905), in which the Supreme Court struck down a state economic regulation for interfering with the constitutional right to economic liberty. "If a majority of the people, after due deliberation, decide to champion such social and economic reforms as those we champion," T.R. would say, "they have the right to see them enacted into law and become a part of our settled government policy." Progressive voters and lawmakers, he maintained, "cannot surrender the right of ultimate control to a judge."

In order to combat Lochner and similar rulings, he declared, "it will have to be made much easier than it now is to get rid, not merely of a bad judge, but of a judge who, however virtuous, has grown out of touch with social needs and facts that he is unfit longer to render good service on the bench."

Cousin Franklin took that notion and ran with it.

'Extraordinary Conditions'

It doesn't take Sherlock Holmes to discover the cause of Franklin Roosevelt's beef with the Supreme Court. The simple fact is that FDR was sore about losing a bunch of big cases. Perhaps his most stinging defeat came on May 27, 1935—"Black Monday," as despondent New Dealers came to call it—when Roosevelt lost three major cases in the course of a single morning, each one decided against him by a vote of 9–0. The most significant of the three was Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, which invalidated the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, the legislative centerpiece of FDR's New Deal agenda.

The Schechter case asked whether the NIRA represented an illegal delegation of lawmaking authority by Congress to the executive. Given the massive number of executive orders issued by FDR under the sweeping law, it seemed as if the president was becoming a lawmaking power unto himself.

Also at issue in Schechter was whether the NIRA, which regulated economic activity down to the most minute local level, amounted to an illegitimate exercise of Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. The Schechter brothers, who operated a kosher slaughterhouse in Brooklyn, New York, sparked the case by running afoul of New Deal regulators by committing such supposed infractions as "destructive price cutting" and allowing customers to make "selections of individual chickens taken from particular coops and half-coops." Not exactly "commerce…among the several states."

The Supreme Court ruled against the New Dealers on both counts. "Extraordinary conditions do not create or enlarge constitutional power," declared the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes. That phrase was widely understood as a direct rebuke of Roosevelt himself. The NIRA must be struck down in its entirety, the chief justice wrote, or else "there would be virtually no limit to the federal power, and, for all practical purposes, we should have a completely centralized government."

FDR was furious. "The country was in the horse-and-buggy age when that clause was written," he complained to the press, referring to the provision giving federal lawmakers the power to regulate commerce that crosses state lines. As far as he was concerned, the country needed a Supreme Court that would "view the interstate commerce clause in the light of present-day civilization."

A reporter then asked the president about his next move against the Court. "We haven't got to that yet," Roosevelt replied. Two years later, having been securely reelected to a second term, he would seek his revenge via the court-packing plan.

'Emphatically Rejected'

Sen. Burton K. Wheeler (D–Mont.) was nobody's idea of a New Deal foe. In 1924, Wheeler was the Progressive Party's vice-presidential candidate, serving as running mate to the famous Wisconsin leftist Robert M. La Follette. Later, as chairman of the Senate Interstate Commerce Committee, Wheeler would play a central role in the 1935 passage of FDR's bill to regulate utility holding companies. Wheeler even had a personal stake in wanting to see New Deal legislation prevail in federal court. When the Supreme Court in 1936 struck down the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 in United States v. Butler, Wheeler's son-in-law, an economist at the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, was tossed out of work.

Yet none of that prevented Wheeler from launching an all-out attack on FDR's court-packing plan. "It is an easy step from the control of a subservient Congress and the control of the Supreme Court to a modern democracy of a Hitler or a Mussolini," Wheeler fumed in a letter to the socialist leader Norman Thomas. Speaking to a national radio audience less than two weeks after FDR forwarded his judiciary bill to Congress, Wheeler went nuclear: "Every despot has usurped the power of the legislative and judicial branches in the name of the necessity for haste to promote the general welfare of the masses—and then proceeded to reduce them to servitude."

As Wheeler led the congressional fight against court packing, he acquired a powerful progressive ally in another branch of government. According to biographer Melvin Urofsky, FDR's "scheme particularly alienated eighty-year-old Louis Brandeis, by then an icon of the liberals and considered by many of them the original New Dealer." Brandeis, a sitting Supreme Court justice, would marshal opposition to the court-packing plan from inside the Court itself.

Another nail in the coffin was driven home by the Senate Judiciary Committee, which issued a damning adverse report on the bill in June 1937. The court-packing plan "is a measure which should be so emphatically rejected," the report stated, "that its parallel will never again be presented to the free representatives of the free people of America." Seven of the 10 senators who signed that document were members of the Democratic Party. The killing of the bill was a thoroughly bipartisan affair.

Ironically, Roosevelt could have avoided the whole embarrassing ordeal if he had just kept his cool and waited things out. By the time of his death in 1945—during his fourth term in office—FDR had appointed eight new justices to the Supreme Court. In the end, he got to leave his mark on the Court without any unsavory meddling with its size.

'I Beat the Socialist'

Is there a Brandeis or a Wheeler among today's Democrats—a figure willing to lead the fight against court packing from inside the liberal coalition?

The late Ruth Bader Ginsburg might have been happy to play the role. It "was a bad idea when President Franklin Roosevelt tried to pack the court," she told National Public Radio in 2019, and it would be a bad idea now. "If anything would make the Court look partisan, it would be that—one side saying, 'When we're in power, we're going to enlarge the number of judges, so we would have more people who would vote the way we want them to.'"

Maybe Joe Biden will consider playing the part. During his 2020 presidential campaign, Biden took pains to distance himself from the extreme left wing of his party. "I beat the socialist," Biden bragged of defeating Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) in the primaries. "That's how I got elected. That's how I got the nomination."

Biden also made certain efforts to distance himself from the growing Democratic calls for court packing. "If elected," Biden told 60 Minutes, "I'll put together a national…bipartisan commission of scholars, constitutional scholars. Democrats, Republicans. Liberal, conservative. And I will ask them to, over 180 days, come back to me with recommendations as to how to reform the court system, because it's getting out of whack." Such a commission, Biden stressed, is "not about court packing."

Of course, Biden also conceded that the composition of the courts is a "live ball" among the Democratic base. But he added that "the last thing we need to do is turn the Supreme Court into just another political football, whoever's got the most votes gets whatever they want."

Unlike Franklin Roosevelt, Biden has yet to see any of his signature presidential accomplishments go down in judicial flames. A few sharp losses at SCOTUS could push him into Roosevelt territory.

Or maybe not. After all, many presidents have lost at the Supreme Court since 1937, including Biden's old boss, Barack Obama. Yet none of them threw an FDR-sized temper tantrum and tried to rig the process for their own benefit. One hopes Biden will follow that historical precedent.

The justices of the Supreme Court may be appointed by the executive, but they answer to the Constitution. No president should ever again launch such a shameful attack on the independence of a co-equal branch of government.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Don't Pack the Courts."

Show Comments (195)