Should We Quit Teaching Cursive in a Digital Age?

While script may wire the brain, connect to history, and come more naturally to many kids, digital print is winning.

Forget Marx vs. Mises. You want to get a spirited debate going, ask pretty much anyone over the age of 8: Should kids still be taught cursive writing?

I posted this question to Facebook, and for the next hour or two, every time I checked in someone was busy typing a response. Which, I think, proves my side of the argument: These folks weren't penning flowing notes on scented paper. They were using the most dominant method of written communication today: keyboarding. When most of your life will be spent tapping keys, why bother to learn two different ways of writing with a pen or pencil?

Because it is super-important historically, physically, psychologically, therapeutically, and cognitively—that's why, said the pro-cursive folks. And as I talked to teachers, therapists, and education gurus, it started to seem to this cursive-challenged gal that perhaps they have a point.

One of script's biggest benefits, they said, is that because the letters are strung together, it makes reading and comprehending easier (yes, even though books are rendered in print).

"First graders who learned to write in cursive received higher scores in reading words and in spelling than a comparable group who learned to write in manuscript," reported researchers in Academic Therapy in 1976. This could be because when a kid isn't lifting his pencil all the time, the linked letters provide "kinesthetic feedback about the shape of the words as a whole, which is absent in manuscript writing."

The gains can go beyond mere reading and spelling to processing whole thoughts. "Kids that write in cursive don't just form words more easily, they also write better sentences," claim the folks at Scholastic.

Is it possible we've been so focused on print that—like a toddler's lowercase bs and ds—we got it all backward? At many Montessori schools, that is the belief. There, kids learn cursive as early as age 3—before they learn print, says Jesse McCarthy, host of The Montessori Education Podcast. Then, using a "movable alphabet" of script letters, "you'll have a 4-year-old on the ground and they're basically writing sentences."

Barbie Levin, an occupational therapist in public and private schools, told me she has seen cursive work almost as therapy for some kids with coordination problems, learning disorders, or cognitive limitations that make it hard for them to learn how to print. "When a fourth grader is referred to me with poor handwriting," says Levin, "I can't unravel the handwriting habits of five years. But if it's within their capabilities…I teach them cursive. It's a fresh start, instead of harping on something they've given up on, and they are learning rather than unlearning. Also, they feel motivated because even 'the smart kids' (who they've been unfavorably comparing themselves to for years) don't know how." Once her kids get the hang of script, she says, they often do better not just at classwork but even at things like tying shoes and buttoning buttons. It's a win all around.

Beyond that, says retired elementary school teacher Michele Yokell, who was teaching an after-school class in cursive right up until COVID-19 hit, script "is part of our history—our heritage." You don't want kids squinting at the Constitution as if it's in cuneiform.

Yet despite all these boons, cursive seems to be going the way of the IBM Selectric—and for the same reason. While script may wire the brain, connect to history, and come more naturally to many kids, digital print is winning.

Cursive is not required by the Common Core curriculum, though a few states have mandated it. And a survey of handwriting teachers by Zaner-Bloser, a cursive textbook publisher, found that only 37 percent of them write exclusively in script. Another 8 percent write only in print, while most—55 percent—use a print/script mashup.

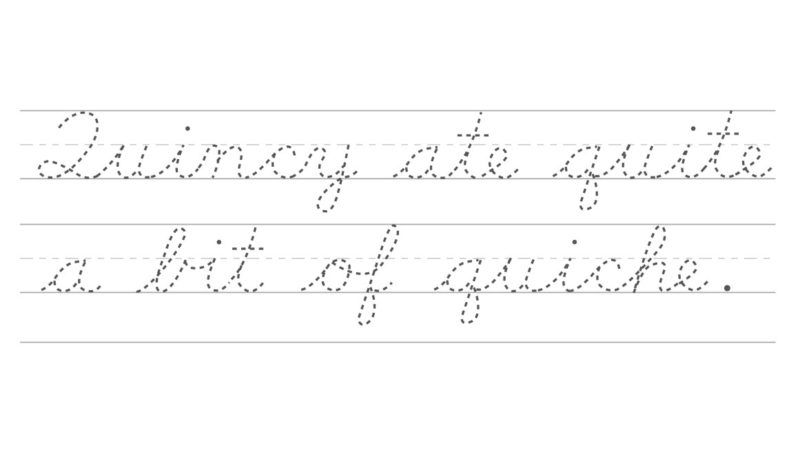

As do I. But 99 percent of my writing time involves a keyboard. So, sure, give kids a chance to learn script if print is tough for them, or if they want to research anything older than Betty Crocker recipes. Or maybe teach script and skip print. But teaching two ways to write the same letters when a third way—tap tap tap—is the real skill everyone needs? That seems as wacky as writing a capital Q that looks like a 2.

Show Comments (92)