A Professor Tried To End a Flirty Email Exchange With a Young Woman. Then She Threatened to Blackmail Him.

When the grad student threatened to publicize their embarrassing correspondence, he reported her. But the university decided he was the villain.

It began, unlike most epic love stories featuring two cosmically intertwined souls rediscovering their connection from some past life, in the printer room of the University of New Mexico's Anderson School of Management.

It ended with a graduate student attempting to blackmail a professor into continuing their flirtatious banter, a sexual harassment investigation that treated the blackmailer as a victim, and, ultimately, a one-year unpaid suspension for the professor.

The professor made serious mistakes. He shouldn't have let the conversation become romantic and sexual—an exchange he actively participated in. He shouldn't have floated the possibility of hiring the student for a low-paid research position—an opportunity she initially expressed interest in taking, then turned down, and then used against him when he rebuffed her, according to documents obtained by Reason.

But the professor and the student never slept together. She never worked for him, and she never took one of his classes. They never even met in person, except for their initial five-minute introduction.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) has taken the professor's case, and it is urging the university to reverse course.

"The university reached conclusions that defied reason and were completely at odds with all of the established facts of the case," attorney Samantha Harris, a vice president of FIRE, tells Reason.

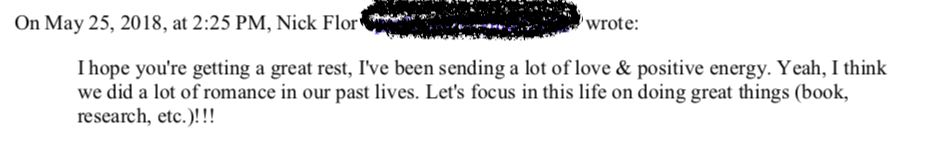

His name was Nick Flor. A tenured professor at the university, he had taught information systems and digital marketing for the past 17 years. He was in his 50s, married with kids.

Her name, for the purposes of this article, was Julia. (I have changed it to protect her anonymity.) She was a graduate student in her 30s. She was fond of hummingbirds, flowers, and astrology.

Julia knew someone who had taken one of Flor's classes some years back, and when she saw him in the School of Management, she took the opportunity to introduce herself. It was a fleeting encounter that lasted all of five minutes, but Julia followed it up with an email to Flor the next day—May 10, 2018. She asked whether he was teaching any classes in the fall.

"I am glad we crossed paths the other day…." she wrote, ending the thought with ellipses, as was her habit. "It was likely meant to happen, as are most if not all things in the Universe….."

Flor wrote back that he would not be teaching in the fall, but would be happy to chat with her about her academic interests.

Over the next two months, Julia sent Flor 3,258 emails and 174 text messages. Flor sent 2,218 emails in response—though his replies were usually shorter—and 11 text messages. Reason obtained and reviewed all of these messages.

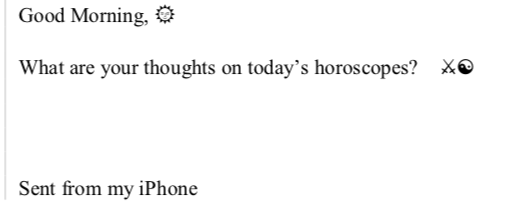

The content of Julia and Flor's correspondence became romantic, and then sexual. Julia sent Flor romantic songs, love horoscopes for their signs, and called him "babe." She suggested cuddling, he suggested kissing, she expressed a desire for it to lead to something more, and so on.

Flor says he eventually realized what he was doing was wrong—among other issues, he was married—and tried to de-escalate matters. When he stopped responding to her messages as often as she would have liked, she threatened him. When he appealed to his department for help, he became the subject of an investigation. And after a procedure that he says violated his due process rights, he was found guilty of quid pro quo harassment.

Flor says he knows he shouldn't have let the relationship develop the way it did. "I can't excuse my behavior," Flor tells Reason. "I exercised poor judgment."

But he's apoplectic at the idea that his conduct could be deemed sexual harassment, when the harassment—as evidenced by the full investigative file, which was obtained by Reason—went in the other direction.

"They're treating me like I'm Harvey Weinstein," he says.

Julia told the university's investigators that she did not harass Flor, that it was he who pushed their conversation into sexually explicit territory, and that she felt compelled to keep it up because she worried not doing so would negatively impact her educational opportunities.

"I believe that Professor Flor should be fired," Julia wrote in her victim impact statement. "Going through this process, and in particular, being the subject of retaliatory action and conduct by an instructor for exercising my civil rights has been nothing short of excruciating, daunting, and overwhelming. I have had to witness and endure, first-hand, the reality and influence of the power dynamic a faculty member inevitably and undeniably has over a student."

Through her attorneys, she declined to comment for this article.

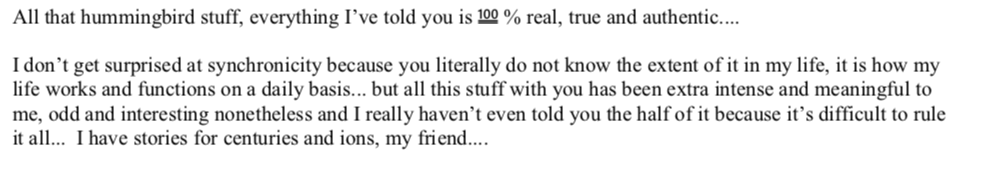

After the encounter in the printer room, Julia began earnestly conversing with Flor electronically. She was quick to stress that she believed their meeting was destiny and that it would be foolish to "take such synchronicity for granted."

Flor's initial responses were polite but curt. He provided answers to her questions about which classes she should take, whether she should go to law school, what the university's Organization, Information and Learning Sciences program was like, and other things.

Within a few days, Julia had shared that she was nearly killed in a car accident years ago and that she possessed lingering pain because of it.

"I'm a licensed therapist, in my own healing journey, but yet still," she wrote, "cannot find anyone to help me heal or feel better…."

Julia also expressed an interest in gossiping about other faculty members—hidden insights, she claimed, that Flor would find "hilarious, intriguing, and mysterious." Flor suggested switching to their personal email addresses or Google Hangouts for such conversations. One of her first messages was a picture of a male faculty member and an attractive woman standing next to each other on a golf course. Julia had circled the woman's breasts, and the man's crotch area, suggesting there was something going on between them.

Soon Julia was drawing hidden connections everywhere. She found it interesting that Flor had tweeted about hummingbirds right after she had seen—and attempted to photograph—precisely such a creature. Flor replied that this was bewildering. "Wow, maybe it wasn't chance that we met," he wrote back, adding a "haha."

But Julia seemed to think this was no laughing matter. "I really don't think you know how synchronous this all really is," she wrote, sending him a picture of a hummingbird landing on a yellow flower. Flor pointed out that his last name meant flower, which pleased her.

Next came love songs—"Past Lives" by the musician Borns was a favorite—and horoscopes. Julia indicated that she expected Flor to actively interpret and respond to them, and she did not appreciate it when he failed to take them seriously enough. She became distraught when he referred to a psychic she admired as crazy, though for the most part Flor passively agreed with Julia that a mounting pile of evidence suggested they were connected in some way. Julia informed him that although he was 20 years her senior, they were actually both ageless—possibly having lived many lives before their current one.

Over the course of May, the conversation became steadily more romantic. Julia frequently referenced her pains, both physical and spiritual. Discussions of coping techniques led to a proposed massage and escalated from there. These were followed by sexually explicit, graphic messages—sent by both Flor and Julia.

"I don't even know what came over me," Flor says. By early June, he had realized he was making a terrible mistake, and it was time to wind down their romantic conversations.

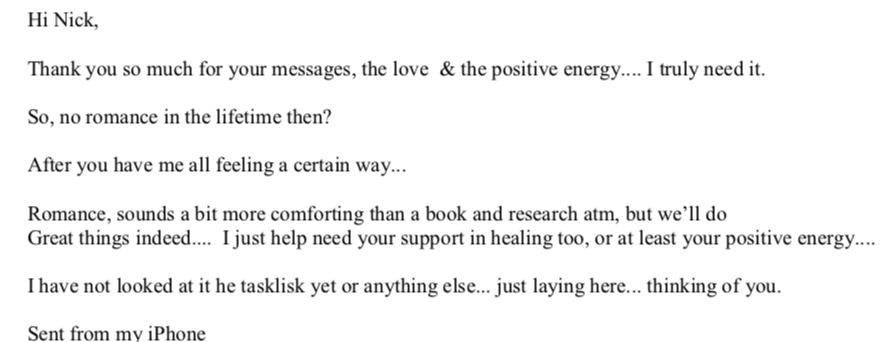

Julia was routinely sending lengthy declarations of love and descriptions of the kinds of emotional, physical, and spiritual pain she wanted him to help her heal. But by the beginning of June, she had noticed that he was barely responding to her emails.

"So what do you have against chatting with me?" she wrote, adding "just curious."

She accused him—in half a dozen separate emails—of killing the romance. He had broken her heart, she said, in this life and in her previous ones. She alternated sending messages contemplating suicide, and pictures of flowers.

During the month and a half of correspondence, Julia and Flor had briefly discussed the possibility of her working a few hours each week as his assistant doing data and analytics. As the messages make clear, he proposed using leftover money from a National Science Foundation grant, which came to a grand total of $703. That meant 35 total hours of work, spread out across 7 weeks.

They couldn't quite work out the logistics, and Julia declined the offer in a June 9 email. But a few days later, she asked about it again. By this point, Flor had quite sensibly decided to spend the money elsewhere, on new equipment, and told her so.

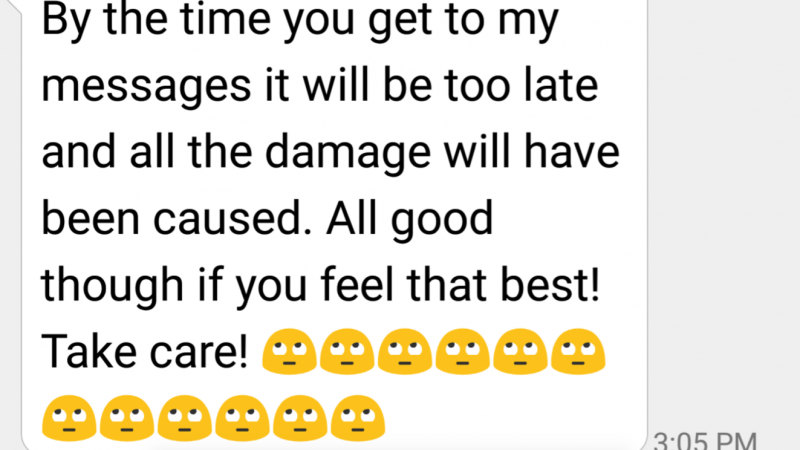

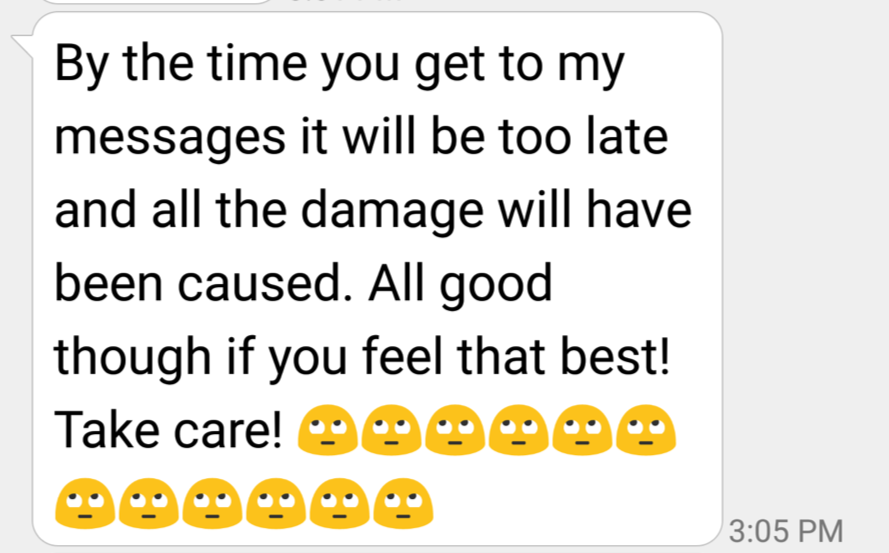

It was on June 24 that Julia made her first threat. She referenced Flor's boss, and asked what he would think if she sent the boss screenshots of their romantic correspondence. Flor stopped responding to her emails, so she began texting him.

"I'll also unfortunately keep on this til it's addressed," she said, referencing Flor's refusal to answer her. "I'm still relentless."

She also began stalking him on social media, sending him screenshots of a tweet he had liked. This tweet belonged to another female student.

"That's what made her go ballistic," Flor recalls.

The texts came at all hours of the day. On June 29, Julia texted him every few minutes, from 5:20 a.m. until 8:30 a.m. Over and over again, she repeated her threat to embarrass him by making public their earlier conversations.

Flor says he realized he could no longer ignore her threats, and felt he had no choice but to inform the university administration. He told his boss that he was experiencing harassing behavior from Julia, and his boss reported the matter to the university's Title IX office, which deals with gender and sex-based misconduct. Flor met with the university's compliance specialist on July 2. According to the investigative file, he told the specialist that Julia was harassing him because he would not pursue a relationship with her.

When Julia learned she was the subject of a Title IX investigation, she filed her own complaint, accusing Flor of quid pro quo harassment and retaliation. The university referred the matter to an independent investigator, who interviewed both parties over the next few weeks.

Flor had to come clean to his wife, something he described as "the hardest part of all of this." They talked about everything, and though his behavior damaged their relationship, Flor says they have stayed together.

"It's so hard to recover from," he says. "But I feel like our relationship is stronger now because we talk so much about it."

At the end of November, the independent investigator issued his preliminary findings, subject to comment from both Flor and Julia. Flor says at that point his attorney was optimistic.

Two weeks later, Flor learned that the university had taken the independent investigator off the case and replaced him with a woman, the interim Title IX coordinator at the university's Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). The documents informing Flor of this development included no explanation for it.

The interim Title IX coordinator then ruled that Julia had not sexually harassed Flor. In fact, her threats to publish their correspondence was "good faith civil rights protected activity," the coordinator wrote in her report. The coordinator went so far as to dismiss the idea that revenge played any part in Julia's decision making: Rather, "she presents as a very hurt individual grasping for some sort, any sort, of communication from a former lover." (Again, Flor and Julia had never had a physical relationship.)

Flor did not get off so easily. The report found him responsible for quid pro quo sexual harassment and retaliation. In the OEO's view, Julia might have believed that she needed to send him sexual messages in order to get the research position—a classic example of quid pro quo harassment. Flor's decision to report Julia's threats constituted retaliation.

"They kept her retaliation complaint but threw away mine," says Flor. "They found me guilty. I don't see how."

The case went on for several more months, as Flor filed a series of fruitless appeals. Finally, in October 2019, it was time for sentencing. I spoke to Flor a few days before the hearing. He told me he was expecting to get off lightly: a 30-day unpaid suspension, perhaps. That had been the punishment, Flor recalled, when the university disciplined a football coach.

"It seems like that's the worst thing they do to you," says Flor.

On October 17, I received a frantic email from Flor. "It is worse than I ever imagined," he wrote. The university had suspended him without pay for a full year.

The university declined to comment about the case, replying instead with a boilerplate statement."The University of New Mexico abides by [university] policies and state and federal laws relating to disciplinary matters," a spokesperson wrote in an email to Reason. "It is our practice not to discuss individual personnel matters."

Julia would have preferred an even stronger sanction, according to her victim impact statement.

"Submission to the sexual advances were the basis of Professor Flor's offers of employment to me," she wrote in calling for his dismissal. "I was forced to make a decision: either 1) tolerate the increasing misconduct, sexual advances, and harassment from a professor in order to receive a Graduate Assistant/Project Assistant position and advance in my field and school of study, or 2) report the misconduct and policy violations. When I decided I had to report Professor Flor's conduct things went from bad to exponentially worse because he chose to use his might to fire numerous false and retaliatory statements and allegations against me."

Samantha Harris of FIRE believes the university has violated Flor's due process rights.

"This is one of the most egregious cases of university malfeasance that I have seen in my nearly 15 years with FIRE," Harris says. "The university found Professor Flor responsible with zero due process—no hearing, no opportunity to question his accuser—in a case where credibility was of critical importance."

It has become much more common over the last decade for universities to adjudicate misconduct—particularly sexual misconduct—in a manner that disregards due process. In 2011, the Obama administration's Education Department released a "Dear Colleague" letter that contained new requirements for publicly funded educational institutions. The department's Office for Civil Rights instructed colleges and universities to take sexual misconduct accusations much more seriously, and to investigate them using a framework that would minimize the possibility of retraumatizing the victim. This meant lowering the burden-of-proof threshold to a preponderance of the evidence, defining misconduct broadly as "any unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature," and discouraging investigators from allowing cross-examination.

The result was that many schools stopped holding adjudicatory hearings altogether, and instead moved to a single-investigator model, in which one administrator would decide which witnesses to question, produce a report based on these interviews, and then recommend a finding. Such procedures give accused parties very little opportunity to present evidence on their behalf.

Last year, under the guidance of Sec. Betsy DeVos, the Education Department rescinded its previous guidance. But many universities have vowed to continue operating as if nothing has changed.

Flor's case is emblematic of this widespread abuse of the rights of accused students and professors. In a letter to the university, Harris wrote that the OEO's findings do not establish that Flor "implicitly or explicitly conditioned employment on submission to sexual conduct." On the contrary, FIRE points out, Julia declined the position after Flor had ceased his overtures. She was not interested in working with him if they were going to be mere work associates. Flor did not condition Julia's employment on a romantic relationship—Julia did.

FIRE's letter notes that Flor never received so much as a hearing, let alone an opportunity to cross-examine his accuser. He was not able to pose questions that a panel might ask of Julia. He was not able to present witnesses on his behalf—even though he knew of another professor who had received similar correspondence from Julia and would have been willing to appear on his behalf.

Indeed, documents forwarded to Reason by Julia's attorneys make reference to this other professor, Smith. (I have changed his name to protect his anonymity.) Julia had also accused of Smith of sexual misconduct following an email- and text-based relationship that failed to yield an employment offer for her, but OEO cleared Smith of wrongdoing. On October 8, Julia wrote to the university's board of regents, urging them to reverse this decision and sanction Smith. According to Julia, Smith broke off contact with her after his wife demanded that he do so.

"Professors must not dangle promises of job and project opportunities in front of a student with whom they are communicating with in a personal nature and then use their wife as an excuse to retract the offer and all communication," wrote Julia in her appeal. "This decision was based on sex/gender and directly violates University Policy."

Smith did not respond to a request for comment.

On November 13, Flor inquired about the outcome of a separate investigation: The university had also sought to determine whether he had violated Policy 2215, which deals with consensual relationships and conflicts of interest. This investigation had determined that Flor "did not exercise authority over a subordinate," since he had not been teaching, supervising, or evaluating Julia. In this case, he had been cleared.

But according to Flor, the university only belatedly informed him of this important fact after he asked about it. If he had been told in August, when the decision was reached, he could have cited the outcome in his appeals concerning the Title IX matter.

"I look at this as withholding exculpatory evidence," says Flor.

In the meantime, Flor can't even look for alternative long-term work. The University of New Mexico has a policy prohibiting employees from working at any other job for more than 39 days per year. Flor asked the administration if he still counted as an employee during the term of his suspension. He was informed that he did.

He's also worried that he will never again receive any grant money, since the OEO reported his Title IX violation to the National Science Foundation.

Flor is currently waiting for the outcome of another appeal. This "peer review" appeal, permitted under university policy, gives faculty members the power to review the appropriateness of a colleague's sanction. They could opt to lessen Flor's punishment, though his suspension—which goes into effect on January 1—is likely to begin before the faculty reach any kind of decision.

"FIRE will not rest until Professor Flor gets some justice in this egregious case," says Harris.

Show Comments (178)