When the Cops Come for You in the Target Parking Lot

A mom reflects on her experience parenting in the age of fear.

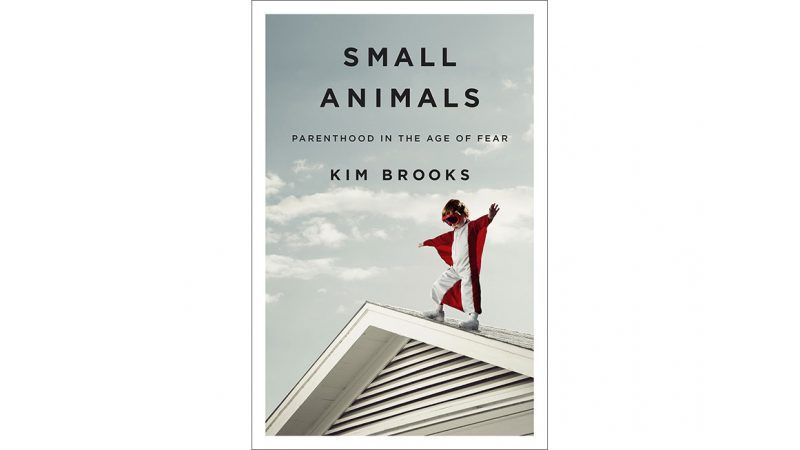

Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear, by Kim Brooks, Flatiron Books, 256 pages, $26.99

As the father of a toddler, I am uncomfortably familiar with parenting in an age of fear. I bristle when my son runs (always without looking) out of my sight, even though I know that parents overestimate the risks to their children's safety. And while I'm familiar with the reasons that parents shouldn't always solve their children's problems for them, I confess that when some kid snatches something from my son, I have to suppress the instinct to intervene.

So I looked forward to reading Kim Brooks' Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear, and the book did not disappoint. Brooks is a mother of two who, faced with a time crunch and an uncooperative 3-year-old, went into a Target store for around 10 minutes while her child played in the car on a tablet. A "concerned citizen" saw her leave the car without her kid, snapped a photo, and called the police. In the world we live in, Brooks was seen as the one in the wrong; the busybody who called the cops was just doing the right thing.

Small Animals is Brooks' attempt to figure out what happened, not just to her but to us. Intertwined with her own story, told from incident to aftermath, she talks with people who know something about parenting in this fearful culture. They include a social worker, a cognitive psychologist who has studied how parents appraise risk, a lawyer, and many parents—including Reason columnist Lenore Skenazy—who have similarly been accused of (and in some cases arrested for) supposed parental negligence.

Two things must be said at the outset. First, Brooks is not writing simply to vent her frustrations or shock readers with stories about "parents and cops these days." She really is trying, as sympathetically as possible, to understand the modern trend of fearful parenting. Second, she does not hold herself above the trends she laments. Some of the most intriguing and relatable parts of the book come when she discusses her own internal tensions—knowing how absurd some parental worries are while not being able to free oneself from them.

For instance, after an initial chapter rehearsing the incident that led to the book, she recalls her days as a mother-to-be. This, she tells us, is where it started. Every doctor's visit or talk with experienced parents turned into advice sessions of stern do's and don'ts. Doctors gave her pamphlets; parents recommended the latest manuals. What Brooks realized only afterward is that "knowing, as anyone with an anxiety disorder can tell you, is one step away from controlling." As kids get older, the expectation that we keep this control intensifies: We send them to schools that micromanage how they learn and behave, schedule them for after-school activities controlled by adults, and feel persistent pressure never to let them too far out of reach.

Brooks notes that, by and large, we are doing this to ourselves. Yes, her Target incident led to an unfortunate run-in with the police, but it was a citizen who snapped a pic and called the authorities. And much of the pressure that parents face doesn't involve the government at all. As Brooks writes, "If parenthood is no longer just a relationship or a part of 'ordinary life' but instead a new kind of secular religion, then true tolerance of each other's parenting differences becomes a lot more complicated and a lot less common."

So what happened to us? Brooks offers many theories. The media exaggerate the dangers of the modern world, and we seem to have responded accordingly. As the race for jobs and college admissions grows (or at least appears to grow) more competitive, parents worry that easing back means sabotaging their children's futures. There may even be some sexism here—there is evidence that women experience much more negative judgment than men when they aren't attending to their children.

One of the most compelling parts of the book comes toward the end, when Brooks discusses what this cultural shift does to parents and to kids. One mother suggests to Brooks that parenting in an age of fear means that she remembers precious little of her children's actual childhoods; she just remembers the fear and anxiety. "Perhaps this was the greatest cost of fear," reflects Brooks, "the way it blots out everything it touches—drowning out the joys of parenthood, deadening the very thing we hoped it would protect." Children experience a similar deprivation: the loss of self-efficacy, of the confidence and ability to solve their own problems, of knowing any aspect of life free from adult monitoring.

As a side note, Brooks mentions that when she started writing on these issues, she noticed to her surprise that libertarian outlets like Reason were sympathetic. To her mind, overprotective parenting just wasn't an obvious libertarian issue, since "the parent-child relationship makes it impossible to talk about parenting strictly in terms of individual liberty." Yet when Brooks tells stories of hovering parents and overprotected kids, she is telling stories about individual liberty, where neither parent nor child is terribly free. In an age of fear, "whatever [parents] have to do to feel safe…we vow to do it, to pay whatever price is set for a feeling of safety, a feeling of control." Yet again, prizing safety above all else is how liberty is lost.

Reading Small Animals was a sort of therapeutic catharsis. Brooks is short on solutions, but her gifts at introspection in telling her own parenting story are sure to resonate with parents. They certainly did with me.

Show Comments (42)