The Confidence-Man

Friday A/V Club: Long before "fake news" was a cliché, Alan Abel was both inserting and exposing fakery in the news.

I keep hearing that we live in a Post-Truth Era, and I keep wondering when the Truth Era that presumably preceded it is supposed to have taken place. It certainly didn't happen during my lifetime, and I haven't encountered it in the history books either. We've always been wandering through a fog of misinformation, disinformation, urban legends, and dubious guesses, and while I don't suppose that's good news in itself, some may find it reassuring to realize that it isn't a new development.

With that in mind, let's raise a glass to the writer, drummer, filmmaker, comedian, and infamous media prankster Alan Abel. Long before the phrase "fake news" became a cliché, he was both inserting and exposing fakery in the news.

"I tested the gullibility of the New York Times by running my own obituary," Abel told Re/Search in 1987, "and it felt like The Twilight Zone when I read it. They gave me a great write-up; it was so well-written—they crammed into six paragraphs everything I'd ever done." The Times published that obit for Abel in 1980, nearly four decades too early.

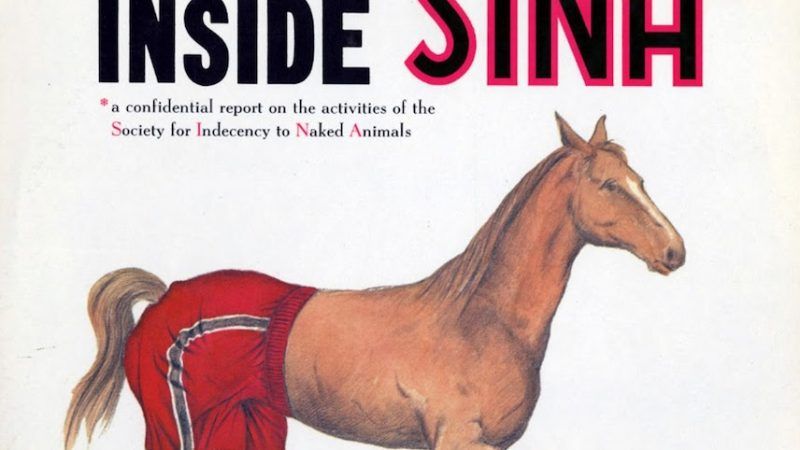

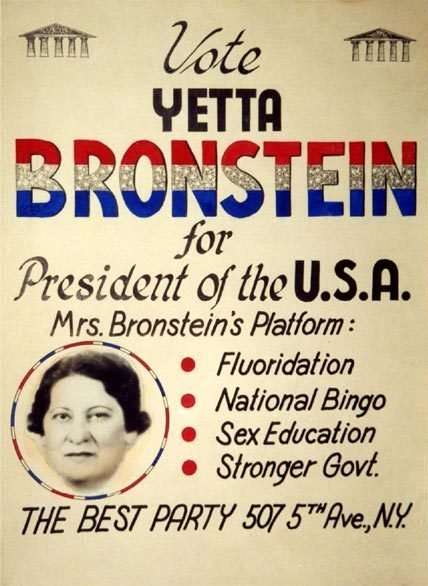

Last week, Abel really did die. Or so I read in The New York Times, which ran a new obituary under the good-sport headline "Alan Abel, Hoaxer Extraordinaire, Is (on Good Authority) Dead at 94." The piece gave due attention to the time he persuaded the Times to prematurely pronounce him deceased, along with various other pranks that Abel and his allies carried off over the years. There was the Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (SINA), launched in 1959 by Abel and a young Buck Henry, who attracted credulous coverage by posing as bluenoses offended by the sight of animals without clothes. There was Yetta Bronstein, played for the press by Abel's wife Jeanne: a fictional New York grandmother who ran for president in 1964 and '68 on a platform of flouridation, sex education, a national bingo tournament, and replacing congressmen's salaries with commissions. There was the Ku Klux Klan Symphony Orchestra. There were the Euthanasia Cruises. There was Females for Felons, described in the Times obit as "a group of Junior Leaguers who selflessly donated sex to the incarcerated." Abel's website has long list of his media pranks, including incidents where he or a confederate fooled reporters by posing as Howard Hughes, as Salman Rushdie, and as Deep Throat.

And then there was the faint-in on The Phil Donahue Show. During a 1985 episode of the program, the website recounts, "Abel planted several of his pranksters in the audience. As per Alan's instructions they stood up, one by one, to ask Phil a question. And as soon as the microphone came near, they collapsed onto the floor." The unconscious actors piled up, and the audience was eventually evacuated.

Abel told the press that he did that to protest the sensationalism displayed on shows like Donahue's. But he may have been deliberately fanning that sensationalism too, if you credit the account he gave to Re/Search:

I used to write material for Phil Donahue when he was a talk show host back in Dayton, Ohio. Phil went to Chicago where he remained for eighteen years. Then in 1985 he moved to New York. I got a call from one of his assistants who said, "It's very important that Phil's new show gets good ratings in New York. Why don't you come up with some media stunt, and if it works, and doesn't kill anybody or hurt anyone, you'll be well-paid." I thought about it and came up with this idea….Donahue was very upset when he found out it was a hoax, but his ratings started going up, so he mellowed.

And now you know the rest of the story. Maybe. It's possible that this explanation was itself a hoax.

Abel's most resilient prank was Omar's School for Beggars, an imaginary academy for panhandlers who want to improve their skills at tricking passers-by into giving them money. Created in 1975, it was exposed as a gag fairly quickly; by the time Gannett syndicated a profile of Abel to newspapers in 1979, it was one more caper on the list of successes, described alongside SINA, Yetta, and the rest. Yet reporters kept falling for it. As late as 1988, more than a decade after the truth about Omar had been revealed, New York magazine, The Miami Herald, and the BBC all did their own School for Beggars stories. There was, apparently, a big media appetite for tales about panhandlers conning people—so big an appetite that the marks didn't pause to consider whether they were being conned themselves. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

(For past editions of the Friday A/V Club, go here. For an installment about another media prankster—Joey Skaggs—go here. We covered yet more hoaxes here and here.)

Show Comments (17)