Upset About Budget Cuts to the National Institutes of Health? Blame the National Institutes of Health

The NIH's track record suggest that Trump's proposed $6 billion budget cut won't be the end of science, progress, or discoveries.

Scientists and fans of science are getting all worked up over a proposed 20 percent cut to the budget of the National Institutes of Health. If they're looking for someone to blame for those cuts, they can start by blaming the National Institutes of Health.

Seriously. From funding experiments that gave cocaine to quails and rats, to studying the sex habits of hamsters and goldfish, there are few parts of the federal government that have made a better case for budget cut than the NIH.

Adrienne LaFrance has a piece at The Atlantic that takes the hysteria over President Donald Trump's first budget proposal to new heights. The budget, which includes a cut of $6 billion to the NIH, has scientists bracing for "a lost generation in American science," according to LaFrance, who says scientists told her that the "consequences of such a dramatic reduction in public spending on science and medicine would be deadly."

One of those scientists, Peter Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, tells LaFrance that the proposed cuts "would bring American biomedical science to a halt and forever shut out a generation of young scientists."

Please.

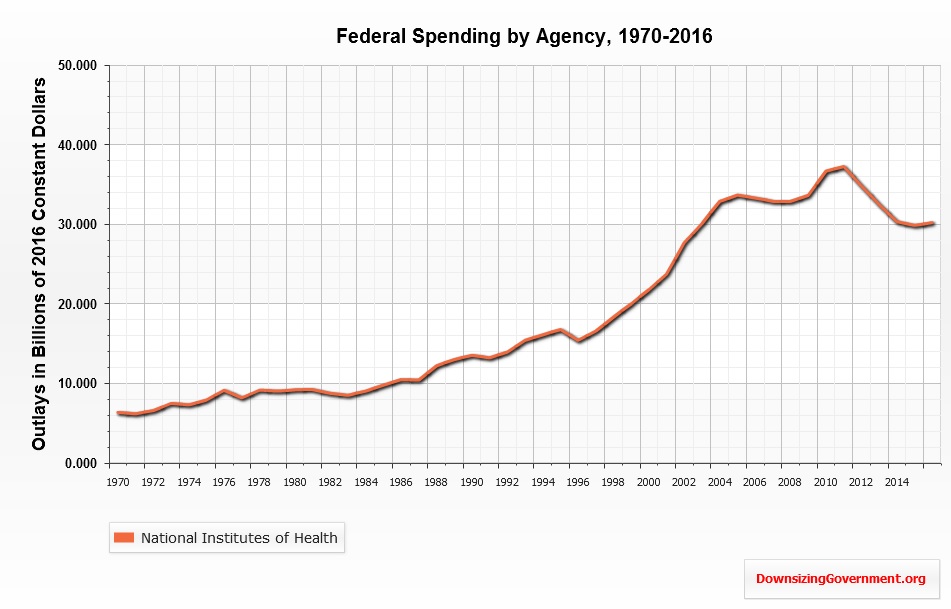

Behind all the hysterics is one simple fact. Even if Trump's budget cuts are enacted, as proposed, by Congress (which they won't be), the NIH would be funded at the same level as it was in 2003. That's less than 15 years ago. It's hardly a return to the Dark Ages—heck, that's hardly a return to the pre-iPhone ages—or to the era when smallpox and polio were running rampant. If the generation of young scientists that went to school in the 1990s and early 2000s managed to survive and get funding for research without the NIH at its current levels, then surely the next generation will.

Before going any further, though, an important note on Trump's budget. It's terrible. His proposed cuts are not a serious effort at reducing the size of the federal government, but rather a way to pay for a mostly useless wall on the border with Mexico and to feed the Pentagon more money ($52 billion more, to be exact), so the military can flush it down the toilet of endless wars, overpriced weapons systems, and who-knows-what-else because not even government auditors can figure out how the Department of Defense manages to waste so much taxpayer money.

The terrible spending decisions in Trump's budget, though, do not make his proposed cuts any less legitimate, and few government agencies have made a better, stronger case for having their own budgets reduced.

More than 80 percent of the NIH's annual budget is used to fund research grants, mostly for universities and post-grad students. While there is plenty of good research funded by the NIH, there's also no shortage of examples that make you wonder if they're secretly conducting a study on how many ridiculous, wasteful studies they can fund before Congress or the president cuts their budget.

Perhaps the most infamous example of pure WTF research funded by the NIH is the $175,000 grant given to the University of Kentucky to study how cocaine affects the sex drives of Japanese quail.

"It's hard to think of a more wasteful use of American taxpayers' money than to give cocaine to quail and studying their sexual habits," deadpanned then-Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Oklahoma) in highlighting the study in his 2011 report on wasteful government spending.

There are plenty of other head-scratching examples, like the $509,000 grant used to study how meth-heads responded to text messages using "gay lingo." The NIH spent more than $2.8 million over four years funding a study to determine why "nearly three-quarters of adult lesbians overweight or obese," and why gay men generally are not. More than $600,000 from the NIH helped finance a study on the sex habits of hamsters, and another $3.6 million from the NIH allowed researchers at Bowdoin College to ponder "what makes goldfish feel sexy?"

My personal favorite is the 2012 NIH-funded study that determined rats on cocaine prefer listening to jazz music instead of classical. Specifically, they like listening to Miles Davis' classic album "Four" more than Beethoven's "Fur Elise." Don't worry, the researchers did the same experiment with rats high on methamphetamine, too, and found that they also enjoy Miles Davis. Cool.

Not to be outdone, researchers at the University of Illinois used a $242,600 NIH grant to get honeybees high on cocaine, ultimately discovering that the intoxicated bees are "about twice as likely to dance" and moved 25 percent faster than sober bees.

Other NIH studies simply prove what everyone already knows, like when a $548,000 grant helped demonstrate that adults over age 30 who frequently binge-drink tend to be less mature than their peers. Or when the NIH spent $666,000 on a study that found watching re-runs of old television shows make people happy, because it gives them an "energizing chance to reconnect with pseudo-friends."

Even when they try to clean up their act, the NIH ends up raising questions about how it's spending taxpayer money. After a government audit found that the NIH had blown $823,000 on a Las Vegas conference (enough to fund five more studies about the drug habits of Japanese quail, can you believe?) in 2010, the agency created new levels of bureaucratic oversight to make sure that didn't happen again. The problem: Bloomberg reported in 2015 that the additional oversight costs as much as $14.6 million annually, roughly equal to how much the agency spends each year researching Hodgkin's disease.

The hilarious examples of waste at the NIH are just a drop in the bucket of the federal deficit, of course, but it certainly seems like the agency could do a little trimming without losing any critical medical research.

Even without budget cuts, that research is increasingly being driven by the private sector anyway.

In her piece at The Atlantic, LaFrance points out that the federal government funded 60 percent of research and development in the United States in 1965. By 2006, however, more than 65 percent of R&D funding was coming from private sources, she notes.

This, we're meant to believe, is a bad thing. A sign that government—that all of us—is not doing its part to finance the scientific discoveries that make the modern world such a wonderful place to live. For shame.

Get rid of the percentages, though, and a different picture emerges. Funding for the NIH has increased by about 3.5 times between 1970 and 2015 (not quite enough to keep pace with inflation, but pretty close). Most of that increase has been in the past two decades. In just five years, from 2000 through 2004, the NIH's budget grew by a whopping 58 percent, and there was another huge boost in NIH funding during the Obama administration's stimulus program (lots of shovel-ready jobs in labs, one assumes).

There hasn't been a reduction in public funding for research and development, but government funding now makes up a smaller portion of the overall pie because privately funded research has grown so quickly that it's overtaken government as the main patron of science. That's not a bad thing! Sure, privately funded research is subject to approval from corporate overlords at times—in her piece, LaFrance quotes an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale who proclaims that only "sexy, hot" science will get private funding, instead of the tedious research that leads to most important breakthroughs—but if that means fewer studies on why rats like Miles Davis, I think we'll survive.

Similarly, I think we'll be okay if a smaller budget for the NIH means the agency has to prioritize important things like research into deadly diseases ahead of questionably useful studies on the drug habits of Japanese birds, the importance of old television shows, and the sex habits of small mammals.

Show Comments (75)