Tell Me, Comrade, When Did Russia Go Bad?

Parlor games for a new Cold War

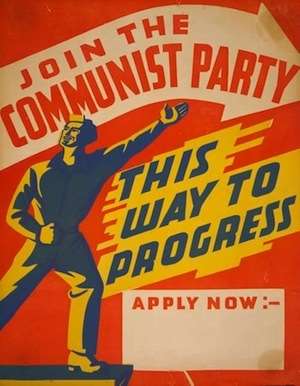

There's an old left-wing debate called When was the Russian Revolution betrayed? (Like many leftist pastimes, this can take the form of either a parlor game or a firefight, depending on the circumstances.) The anarchists think the revolution went sour when the Bolsheviks seized power and transformed the soviets from bottom-up organs of worker control into instruments of the state. The Trotskyists think things went bad when Trotsky lost his power struggle with Stalin, though most of them maintained that Russia remained a "workers' state," albeit a "bureaucratically deformed" one. The "anti-revisionists"—that's Stalinist for "Stalinists"—think Khrushchev's the man who drove the train off the rails. (*) I'm sure there's an old Communist Party stalwart somewhere who thinks the last moment of True Socialism in Red Square came on December 26, 1991, the day the Soviet Union broke up.

Twenty-two years later, there's talk of a new Cold War beginning. Large swaths of the West have given up on post-Communist Russia. But no one's gotten a good game going of When was the Russian Revolution of '91 betrayed? There's a vague sense in the American press that it happened not long after Putin took over, which matches the personality-centric way that power tends to be covered (as well as the fact that Yeltsin is widely seen as a U.S. ally and Putin as an enemy). But while Putin has certainly made thing worse, I remember the moment my pessimism about the new Russia started to outweigh my optimism, and it arrived long before he came to power. It was October 4, 1993, the day Yeltsin had his tanks shell parliament. I didn't doubt that the new order was freer than the Soviet system, of course, but it seemed to be stopping well short of anything appealing.

In those days, setting aside some Bircher die-hards convinced that the apparent fall of Communism was a ruse, my fellow Yeltsin-skeptics tended to be on the left. Now Moscow's most vocal American opponents are the neocons, whose Cold War nostalgia feels like a right-wing mutation of Ostalgie. But my attitude hasn't substantially changed, except for getting bleaker.

If I'm pessimistic about Russian liberty, I'm relatively optimistic when it comes to Russia's place in the world order. Two years before I was born, the Soviet Union sent tanks to a city in the middle of Europe. Nowadays the big Russian foreign-policy crisis involves a dispute over the control of a majority-Russian enclave just over the country's border. While I don't for a moment defend Putin's actions in Crimea, I think I can safely say that in the grand arc of history, this is a better problem to have. And while I don't have sympathy for those Americans eager to thrust this country deeper into that dispute, I can see that they're spouting the frustrated rhetoric of a faction that knows it isn't setting policy. On both sides of the old Cold War, things could be a lot worse.

(* There's probably only five or six people out there who'll agree with me about this, but I think the Encyclopedia of anti-Revisionism On-Line is one of the most endlessly entertaining sites on the Internet. The thing is like a TV Tropes of Stalinism. I'm especially fond of this document from 1980, in which an American Maoist sect's loyalty to Chinese foreign policy leads it to call for a "united front with U.S. imperialism against Soviet imperialism." It goes on to endorse the draft, NATO, increased Pentagon spending, and an American military presence around the globe—but not in Taiwan, since the U.S. presence there "represents support for a comprador, counterrevolutionary separatist faction." Seriously, this is hilarious.)

Show Comments (33)