Inside the Mind of a Big-Time Spender

Senator Proxmire's evolution from "$35-Billion Bill" to taxpayer's friend

For those with an appetite for cynical interpretations of the American political process, the case of Sen. William Proxmire, Democrat of Wisconsin, has been a tasty morsel indeed. On the one hand, he has been a headline-grabbing fiscal conservative, decrying wasteful government spending even before he came to Washington in 1957. As a senator, he developed the well-known "Golden Fleece Award" whereby questionable appropriations are singled out for nationwide ridicule. For symposia on the importance of limiting federal spending, he is probably the most sought-after speaker in the country.

Yet, while being a crusader against government spending, the senator has also been a supporter of the budget-busting expansion of federal programs. He has long fought for subsidies for Wisconsin dairymen; he was instrumental in pushing through the first federal loan program for New York City in 1975; he is a staunch defender of Social Security and the Medicare program.

The cynics assume that they know, without a second glance, what Mr. Proxmire has been up to—namely, a textbook example of hypocrisy. He preaches fiscal conservatism to woo the tightfisted Wisconsin farmers, then plunks for the welfare state to please the liberal-labor pressure groups. It's the old ploy of appearing to be all things to all men—and, the cynic adds, look how well it works. The senator has been reelected five times by wonderful majorities. "Proxmire," in the sour view of Vic Gold writing in Harper's, "can be sure of his niche in the pantheon of irresponsible demagogues."

The trouble with such an interpretation is that it presumes a degree of conscious dishonesty that hardly anyone in real life can sustain for very long. The politician is supposed to project, day after day, a concern bordering on hysteria; a concern which, in his own mind, he knows to be false and empty posturing. As any actor will testify, to play a role even for a few hours is quite draining. To say that a politician has dissembled for over 30 years—which is how long Prox has been hammering at government waste—strains credibility.

So I've never liked the prevailing theory about Proxmire. But I didn't have a good substitute explanation for his behavior—until I began reading his books.

I had set myself the task of trying to understand why congressmen voted for more and more spending even while they said that they knew it was bad for the economy. The paradoxical Proxmire seemed an obvious figure to study. With great interest, I delved into his books on government spending and waste.

One of his earliest books on economy in government was his 1972 work, Uncle Sam—The Last of the Bigtime Spenders. In it one finds, with glaring clarity, the inconsistency that has given Proxmire his reputation. On the one hand, he is fulsome in detailing the failures of government programs, the thoughtless excesses, the corruption, and the "perversion of intent" endemic to government action. But right alongside these findings, often on the very same page, Proxmire declares the "pressing need" for additional and expanded government programs of all descriptions.

For example, he makes devastating criticisms of the housing and urban-renewal programs. He scores them for destroying more housing for the poor than they create, for discriminating against blacks, for mandating the wrong type of housing, for largely subsidizing housing for the middle and upper classes, and for the numerous scandals that plagued the programs. "The major villains were the FHA, HUD, and the Urban Renewal Administration bureaucracies," he concludes. Do his findings make him skeptical of the ability of government to handle the housing problem? Not a bit. "The problem with public housing is that there has not been enough of it," declares Proxmire, who then rushes ahead to congratulate himself for "the establishment of a ten-year housing goal under the Proxmire amendment" to the Housing Act of 1963.

What is going wrong? We can't say that Proxmire lacks the training to handle his job, for he has the highest of academic credentials: a BA from Yale, and an MBA and an MPA from Harvard. Furthermore, he is not the only member of Congress whose thinking takes this turn. His is simply a highly visible case of an error that, to varying degrees, afflicts all who grapple with public policy—and even those who only dream about grappling with it. That error is "policy solipsism."

A 50-cent term, I agree, but we need it because we are dealing with a 50-cent fallacy, one that has caused more tragedy around the world than earthquakes and hurricanes combined. A "solipsist" is one who considers his own thinking to be the only reality and who treats the external world, including the experiences of others, as meaningless. Probably no one adopts this position fully and carries it out in his daily life, it being not only foolish but dangerous. Nature has a way of weeding out people who believe that diesel-electric locomotives that are bearing down on them aren't.

But in politics, it is possible to be a solipsist. It is possible to live in a world of imagined policies and ignore the real world. The actual economy and society are so complex and distant, and the cause and effect relationships therein are so obscure, that we are tempted to believe anything we want to believe. Egotism reinforces this impulse: since we consider ourselves smarter and luckier than others, their failures are not relevant to us. Their automobile crashes say nothing about our need to wear seat belts.

The solipsist is thus a perennial optimist about his own policy ideas. Evidence that similar policies have failed at some other place or time will be disregarded because these failures happened to somebody else. The policy-in-my-imagination is reality; historical experience is treated as fiction. In effect, policy solipsism is adopting the position, I think of it, therefore it works.

This is Senator Proxmire's problem. When he thinks of a policy to correct some national ailment, he assumes his imagined policy will work. Similar policies that have failed or backfired do not call into question the soundness of his own idea. Public-housing programs may have been a disaster, the senator reasons, but my housing programs will work.

This inner conviction affects the senator's critical faculties. When it comes to the policies of others, Proxmire is energetic in identifying the reasons for their failure. In fact he could almost be writing for a sophisticated conservative or libertarian audience. But when presenting his own policy suggestions, his acuity flies out the window.

For example, in evaluating past programs to stimulate the economy, Proxmire roundly criticizes public-works projects on the grounds that the jobs involved tend to become permanent. He then turns around and advances his own program for combating recession, under which, he confidently asserts, "there would be full employment at the end of one year." The centerpiece of his plan is for the federal government to "provide public-service jobs for work in state and local governments." He never considers whether these jobs might not also become permanent (which is, of course, exactly what happened under revenue-sharing).

In a later book, The Fleecing of America, Proxmire discusses the Truth in Lending Law he authored but which, in his opinion, has been "miserably administered." He complains: "The Federal Reserve Board drafted regulations so complex that it took the lender hours to fill out the form, and the borrower got lost trying to read it.…What I had in mind," he laments, "was a simple disclosure statute." After decades of experience with the policymaking process, this lawmaker could still believe that the policy he had "in mind" would soar directly from his brain into national fact, untouched by senators, congressmen, aides, lobbyists, administrators, consumers, clerks, judges—or Murphy's Law.

Before we come down too hard on Senator Proxmire, we should realize that policy solipsism is not an unusual error. In its thrall, some of the great minds of history have been reduced to childish blathering. The first to go on record in this manner was Plato, who wrote the Republic in 375 B.C. Plato's idea was that the evils of his time traced to incompetent political leaders. The solution, he said, was to make kings out of philosophers, like himself, trained especially in mathematics. Once these philosopher-kings were put in charge, the state would function without a hitch until the end of time. Everyone would be assigned a specific occupation by the rulers and happily stay in it; no one would ever criticize the rulers or question their judgment; the rulers would never be selfish, they would never disagree among themselves, and so on.

Each year when we come to the Republic in government class, my first-year college students are appalled at Plato's lack of good sense, at gaps in his scheme you could drive a truck through. They do not reckon with the power of policy solipsism; since the ideal republic was a creation of Plato's mind, Plato's mind accepted it as workable.

Interestingly, Plato got a chance to try out his theories when Dionysius II of Syracuse invited him into his administration as a royal advisor. But being a real philosopher-king was tougher than being an imaginary one. The geometry Plato so earnestly crammed into Dionysius had no effect whatsoever on local politics; revolution brewed as usual and Plato was forced to flee for his life.

Intellect, as we see in Plato's case, is no insurance against the error of policy solipsism. Nor is experience an adequate check. Consider, for example, the persistent attraction of Marxism. There are 34 Marxist-Leninist dictatorships in the world, each a dismal tyranny that has failed even in terms of its own promises. Yet all around the world, Marxist activists and their sympathizers dream of establishing the 35th Marxist-Leninist dictatorship, confident that their revolution will bring freedom, justice, and prosperity. The historical record weighs as nothing against the policy-in-mind.

One sees this lack of skepticism in the way congressmen talk about policies as if they were facts rather than mere intentions. They speak of "programs to feed the poor," or "funds to retrain unemployed workers." Instead, they should be saying "programs aimed at feeding the poor," or "funds intended for retraining unemployed workers." It is solipsism that fuels their optimism. It doesn't occur to them that their ideas might transmute into something else when implemented. They don't consider, for example, that a plan "to educate handicapped children" might actually become, after a series of conferences, a scheme "to send administrators on Hawaiian vacations."

Like Proxmire, the congressmen can notice past failures and can even acknowledge that government programs have made certain things worse. Nevertheless, they believe in and support the program they have in mind at the moment. My policy, they say—without a trace of humor—will correct the problem caused by the policy to correct the problem. Obviously, this attitude fosters the endless expansion of government programs. The operative syllogism becomes, in effect, I think, therefore I spend.

What is the prognosis, then, for policy solipsism? Those concerned with the integrity of the federal government's fiscal policy are deeply interested. Can it be cured, or is it a terminal affliction that only worsens with the passage of time?

The evolution of Senator Proxmire's views gives us something of an answer to this question, and the news is both bad and good. In his more recent work, especially The Fleecing of America, one sees both continuity and change in his perspectives.

The bad news is that the senator has not overcome policy solipsism. Much of the book is devoted to criticizing federally funded research. Examples include an HEW project to teach college students to watch television, a study of a Peruvian brothel, a study of the time it takes to cook hash and fry eggs, a study of why prisoners want to escape from jail, and so on.

The senator goes beyond attacking these studies for asking obvious or silly questions. He points out that oftentimes even worthwhile studies merely repeat existing studies, that the budgets of these projects are typically inflated, that the results are often not put in usable form and not relayed to the appropriate audience, and finally, that taxpayers should not be forced to pay for studies that benefit only one group.

Has he therefore become skeptical of the desirability of government-funded research? Not when it is research that he has in mind. "Coming from the number-one dairy state," he declares, "I strongly favor economic studies with a sensible cost/benefit ratio in support of milk, dairy farmers, or the cow." It never occurs to him that the government studies he has in mind would be open to all the defects he has listed—including the unfairness of having taxpayers "fleeced" to pay for studies of benefit to the dairy industry.

While Proxmire hasn't overcome the flaws in his basic logic, there has been a decline in his enthusiasm for government action. In his most recent book he makes far fewer suggestions for new government programs than in earlier volumes, and he announces, his opposition to numerous spending ideas. His legislative record shows this trend toward fiscal conservatism. In his early years in the Senate, he was an unabashed big-spending liberal. Then–Vice President Richard Nixon tagged him "35-billion Bill" on the basis of his spending proposals in 1958—when $35 billion was real money. Some 25 years later, he has grown much more cautious. In 1983, the National Taxpayers Union ranked him sixth out of the 100 senators in fiscal conservatism; in 1984, he ranked in first place.

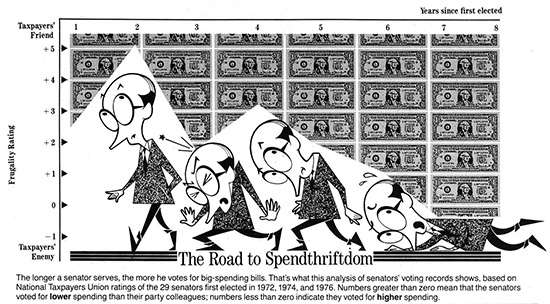

What is significant about Proxmire's evolution is that it goes squarely against the trend. For most congressmen, the longer they serve, the more pro-spending they become (see graph). This relationship, I have found, holds for both free-spending Democrats and fiscally conservative Republicans. Why does Proxmire depart from the norm?

The answer, it seems, lies in the patterns of indoctrination and reinforcement at work. Most congressmen are exposed only to pro-spending influences. They are in contact with beneficiaries of government programs who urge more spending—agency officials whose salaries and prestige depend on the expansion of the programs they administer, pressure groups lobbying for more government largess, and constituents seeking government help for their problems. Exposed year in and year out to the beneficiaries' point of view, most congressmen are swayed toward the pro-spending orientation.

For Proxmire, the indoctrination has gone in the other direction. By a largely accidental process, he has become the recipient of anti-spending stimuli. Proxmire's initial interest in government waste did not come from the heart nor (obviously) from any bedrock convictions about the virtues of limited government. As he frankly explains in The Last of the Bigtime Spenders, he picked the issue of economy in government when he started out in politics because he needed a highly visible theme for his election campaign: "I was desperate; I just had to get elected. How do I identify?"

Once he picked the issue, however, a process of reinforcement began. He directed his staff to work on cases of government misfeasance, and they in turn persuaded him about the wastefulness of government. His reputation as an opponent of waste attracted whistleblowers from within the bureaucracy, whose influence further swayed him away from his natural confidence in government's ability to solve problems.

The good news about the Proxmire case, then, is that it shows what a suitable campaign of persuasion can do to hold back big-spending proclivities. Proxmire began his career with all the makings of a leading big-spender, optimistic about government's abilities to solve problems and afflicted with the thought pattern I have called policy solipsism. Nevertheless, he has drifted far from his fellow liberal Democrats. He has not repudiated his pro-government premises, nor has he overcome solipsism, but the indoctrination by critics of spending has made him one of the most fiscally responsible senators.

The challenge facing advocates of limited government, then, is to figure out ways to bring anti-spending stimuli to bear on the rest of Congress. The congressional-opinion climate—now dominated by beneficiaries—needs to be balanced by the voices of taxpayers and those who criticize specific programs. Legislators are still going to be tempted to believe that their programs will always work. But if they are bombarded with enough new cases of government malfeasance, misfeasance, and bosh, they can be made to shy away from the impulse to spend.

James L. Payne has taught political science at Wesleyan, Johns Hopkins, and Texas A&M University. He is currently working on a book explaining congressional spending.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Inside the Mind of a Big-Time Spender."

Show Comments (0)