When the Smoke Clears

For nearly eight years Alaska has been the only state where the use of marijuana is legal. it's time to take a look at the consequences.

Why should you be bound by rules that say, "Do not handle! Do not taste! Do not touch!" Such prescriptions deal with things that perish in their very use. They are based on merely human precepts and doctrines. While these make a certain show of wisdom in their affected piety, humility, and bodily austerity, their chief effect is that they indulge men's pride.

—COLOSSIANS 2:20-23

On May 27, 1975, the Alaska Supreme Court announced a unanimous decision in the case of Ravin v. State. The ruling held that under the Alaska constitution, the individual's right to privacy takes precedence over any legitimate reason the state might have for prohibiting the personal possession and use of marijuana. Some people panicked at the decision. "Dark days are ahead.…God help the young people of Alaska," wrote one. Another predicted a future of "broken homes, broken spirits, heart-aches, grief, yes, and untimely deaths." Nearly eight years have passed since Ravin—enough time to assess whether the legalizing of personal possession and use of marijuana has had the predicted effects—or any effects—on Alaskans.

The legal opinion that fostered the state's unique approach to marijuana reflects the social character of Alaska's residents. Less than a lifetime ago, most people inhabiting the then-territory lived a lifestyle that was almost neolithic. The changes since then have been breathtaking.

It was only in the 1930s that the indigenous people were first outnumbered by immigrants—often restless persons who disliked their former environments enough to make a radical change. In each ensuing decade, census data indicate that newcomers have outnumbered those who lived in Alaska before that decade. The ballooning immigration has created an aura of constant novelty and the feeling that anything is possible.

A dwindling group remembers Alaska before statehood when to enter the territory, one had to show a birth certificate and submit to batteries of vaccinations. Alaskans had to rely to a great extent on their own abilities and had to take responsibility for their own actions. Doctors and hospitals were rare. Few communities ever saw a judge or a court. With practically no law enforcement, there were very few enforced laws.

The territorial generation had the rare opportunity to devise its own government, constitution, and laws at the time of statehood in 1959. Many of the most conservative territorials were and are radically skeptical of official government pronouncements and strongly defensive of their private lives. One Fairbanksan expressed typically territorial sentiments when, after criticizing the way some of his neighbors lived, he added, "But I don't tell people what they can do on their property, because then they might get the idea that they can tell me what to do on my property."

The territorial generation constituted an electoral majority for the last time in 1972. In the August primary in that year, there ran on the ballot a proposed constitutional amendment that read simply: "The right of the people to privacy is recognized and shall not be infringed. The legislature shall implement this section." This referendum passed by a wide margin, and the right to privacy became Article I, Section 22 of the constitution of the state of Alaska.

By this time, the territorials were beginning to share power with their own sons and daughters and the first wave of 1970s' immigrants. As a rule, the immigrants of the '70s were quite young; at the end of the decade, the median age of Alaskans was 26, the second youngest of any state. Many of the newer residents were veterans who had first-hand experience in Vietnam with both government absurdity and abundant marijuana. They were in a generation that would soon interpret the right to privacy in a way not entirely foreseen by the territorial generation.

The catalyst for the change was the arrest of Irwin Ravin at the end of 1972. Ravin was stopped by Anchorage police for a taillight violation. When instructed to sign the citation, he refused. A search was conducted, a small amount of marijuana was discovered, and Ravin was charged with possessing the substance. He was not totally unprepared for the event; a lawyer himself, he had previously discussed the possibility of a defense based on the right of privacy with fellow attorneys Collin Middleton and Robert Wagstaff. All three agreed that the time was ripe for a test case.

The trial was held in May 1973. Middleton and Wagstaff provided pro bono counsel for the defense, with legal and financial assistance from the Alaska affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union and from the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. A number of local and national authorities were brought in to testify on the assortment of medical and social issues that are perennially attached to the subject, such as the relationships between marijuana and crime, mental illness, reproduction, general health, and public safety. At the conclusion of testimony, Wagstaff moved for dismissal, arguing before the court:

We have shown that there is no compelling state interest of any kind other than oppression, historical bigotry, and hysteria that justifies its intrusion into a protected area and makes criminals out of those who have, in fact, committed no particular crimes. Under the authority of the Alaska Constitution, under our right to privacy…before the state can regulate the use and possession of particular substances, there must be a compelling state interest.

The district judge denied the motion to dismiss and was upheld by the Superior Court; so Ravin appealed to the Alaska Supreme Court. The resolution of the appeal took two years.

In the meantime, in early 1975, the state legislature prepared a bill to decriminalize the private possession of marijuana. Governor Jay Hammond threatened to veto the bill unless changes were made to restrict use in public, in vehicles, and by juveniles. As amended, the bill made possession of any amount in private, or up to one ounce in public, a civil offense carrying a maximum fine of $100. Possession of more than an ounce in public was a criminal misdemeanor. Sale remained a felony.

Decriminalization received legislative approval on May 16, 1975. With the tacit assent of the Republican administration, this Republican-sponsored bill was thus set to become law without the governor's signature.

At this point the first significant public comment was heard. The Anchorage Times, the state's major paper, urged its readers to "put heat on Hammond to veto the bill." The Alaska Peace Officers Association also pushed for a veto. But Hammond responded:

It is hypocritical to criminally punish users of marijuana while legally sanctioning the use of alcohol.…In any event, I could not now veto without the legislature concluding that I had broken my word.…such a course of action would not only be intellectually dishonest but became unavailable to me because of circumstances.

The debate would surely have grown more acrimonious but for the Ravin decision, announced only 10 days later.

Why should my liberty be restricted by another man's conscience?

—I CORINTHIANS 10:29

Written by Chief Justice Jay Rabinowitz, the decision noted first that although the US Supreme Court had inferred some rights of privacy from the Constitution, it hadn't recognized any right to own or ingest marijuana. Nor had courts in Hawaii, Michigan, and Massachusetts accepted that "smoking marijuana was…locatable in any 'zone of privacy.'" The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, for example, had said that "there is no constitutional right to become intoxicated."

Traditionally, courts have considered some rights to be fundamental, not to be overridden by government unless there is a "compelling state interest." Rabinowitz reviewed some fundamental rights of privacy and concluded, "We would hold that there is no fundamental right, either under the Alaska or federal constitutions, either to possess or ingest marijuana."

But that was not the end of the issue. Even if marijuana use and possession isn't protected as a privacy right, said Rabinowitz, the court must take into account the relevance of where the use and possession occur, specifically, "if there is any area of human activity to which a right of privacy pertains more than any other, it is the home." Rabinowitz declared that the Bill of Rights is very clear on this issue. The Third Amendment guarantees against quartering of troops in a private home in peacetime. The Fourth Amendment establishes the right of citizens to be "secure in their…houses…against unreasonable searches and seizures." And "there exist a 'myriad' of activities which may be lawfully conducted within the privacy and confines of the home, but may be prohibited in public."

From this, Rabinowitz inferred that Alaskans do have a right to privacy that encompasses the "possession and ingestion of substances such as marijuana in a purely personal, non-commercial context in the home unless the state can meet its substantial burden and show that proscription of possession of marijuana in the home is supportable by achievement of a legitimate state interest."

But what "legitimate state interest" could there be? How could personal use of marijuana in the home affect the "public welfare" and thus be vulnerable to state prohibition? Rabinowitz noted that the state had presented scientific and medical reports of potential danger from marijuana use but that "in almost every instance…reports can be found reaching contradictory results."

And he read between the lines: "Possibly implicit in the state's catalogue of possible dangers of marijuana use is the assumption that the state has the authority to protect the individual from his own folly, that is, that the state can control activities which present no harm to anyone except those enjoying them." But earlier privacy cases, he pointed out, had established "that the authority of the state to exert control over the individual extends only to activities of the individual which affect others or the public at large as it relates to matters of public health or safety, or to provide for the general welfare. We believe this tenet to be basic to a free society."

The court accepted two legitimate state concerns—the potential for harm caused by drivers under the influence of marijuana and the possibility that use of the substance might spread among' adolescents—but "these interests are insufficient to justify intrusions into the right of adults in the privacy of their own homes." Such intrusions had to cease—and did, with the Ravin ruling.

God did not make death, nor does he rejoice in the destruction of the living. For he fashioned all things that they might have being; and all the creatures of the world are wholesome, and there is not a destructive drug among them.

—WISDOM 1:13-14

For years, advocates of marijuana prohibition have argued that the dangers ascribed to the plant are far more threatening to the fabric of American life than are legal constraints on its use and sale. It has been suggested that if people were allowed to smoke marijuana with impunity, the country would end up populated by a majority of addicted criminals; drivers would run amok on the streets and highways; the national socioeconomic machinery would slow to a halt as otherwise productive citizens spent their time in a haze; children would become unteachable; lung, brain, and chromosome damage would be widespread.

For eight years, people in Alaska have been allowed to smoke marijuana and it is difficult if not impossible to find any data to support the most dire predictions. One is less aware of the presence of marijuana in Anchorage than in most major cities in other states. Complete strangers have offered to sell me marijuana in Houston, Honolulu, and Seattle—but never on the streets of Anchorage or Fairbanks. Despite personal legalization, public display is negligible.

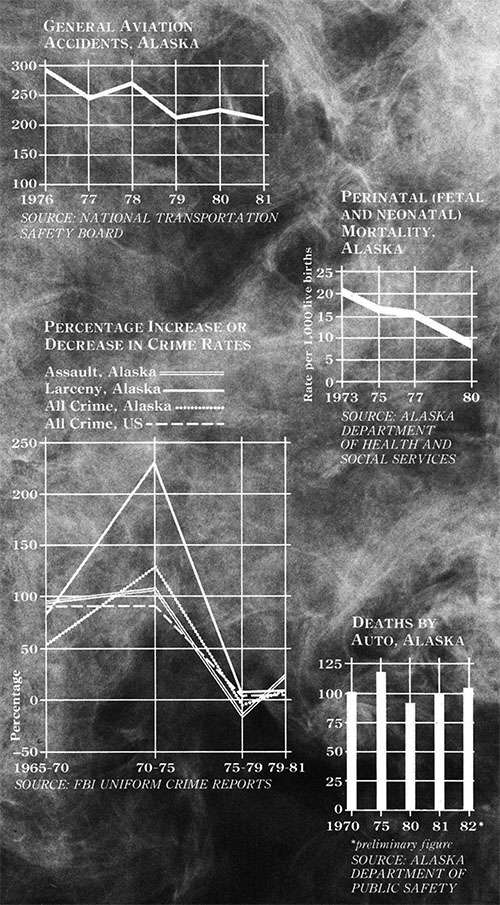

There has been no increase in automobile deaths or aircraft accidents since Ravin; in fact, those rates are stable or declining. There have been no unexplained epidemics of infectious diseases, birth defects, or infant deaths. Alaska's crime rate—ferociously high since the arrival of the first immigrants—is growing at a much slower pace than it did prior to the decision and currently reflects the national norms more closely than at any time since such statistics were first gathered. (See charts, p. 34.)

There is no evidence that young people are using marijuana any more frequently now than they did before Ravin. The most authoritative post-Ravin survey of drug use by Alaskan high school students was being conducted at press time by Bernard Segal of the University of Alaska (REASON was unable to obtain preliminary results from the Anchorage school district). But less formal reports consistently indicate that early predictions of a generation lost to marijuana simply haven't come to pass.

SAT scores for Alaskan students are the highest in the nation and since Ravin have occasionally bucked the national trend of declining scores. The learning abilities, or at least the test-taking abilities, of Alaska's young people do not seem to be suffering unduly.

The point is certainly not that these statistics are the result of the Ravin decision. What is beyond dispute, however, is that no measurable social problem has resulted from allowing adults the freedom to use marijuana.

There might even be some benefits. One positive consequence of Ravin is undoubtedly the feeling of relief that Alaskans who use marijuana must feel now that they are no longer "criminals." It is of course impossible to know just how many citizens have benefited from the lifting of the legal stigma; but if the percentage of Alaskans who have ever smoked is no greater than the national average of 30 percent, this would mean that more than 110,000 individuals who would be on the wrong side of the law elsewhere are left alone in Alaska.

Finally, because Ravin protects possession of marijuana only for personal use—which means that smuggling and sales are still illegal—many Alaskans have chosen to take up home cultivation as the most convenient way to obtain their private supply. (In some rural areas, where outdoor growing is possible and wild specimens are plentiful, a majority of the citizens may actually be subsistence growers and cultivators.) This too benefits a state such as Alaska where, with no significant manufacturing or agriculture, in-state revenue is totally dependent on the export of limited natural resources. Each time a homegrown subsistence product is used in place of an imported black-market consumer product, money that would otherwise be winging its way elsewhere stays within the local economy.

It is not what goes into a man's mouth that makes him impure; it is what comes out of his mouth.…Do you not see that everything that enters the mouth passes into the stomach and is discharged into the latrine?

—MATTHEW 15:11, 17

It would be wrong to think that marijuana is no longer a political issue in Alaska. Last year, conservative pressure groups succeeded in pushing through new legislation that reinstitutes criminal penalties for possession of more than four ounces of marijuana. It went into effect in October; but Ravin defense attorney Robert Wagstaff contends that the new law runs afoul of the Ravin decision and would probably be declared an unconstitutional invasion of privacy if and when it is ever enforced. Indeed, Tom Fink, the Republican gubernatorial candidate last year and an opponent of legalization, observed in an Anchorage Times column that it would probably take a constitutional amendment to override the Ravin ruling. Although there is clearly opposition to unrestricted personal marijuana use, such a constitutional amendment is not an immediate prospect.

In a sense, Alaska was the obvious place for the legal frontier of marijuana legalization to be crossed. Much of the territorial generation and the immigrants of the '70s shared a belief that there is no way to restrict intimate personal activity without undermining for all the citizenry the most important freedoms of the republic, and they accept that prohibitions based on misinformation—no matter how well intended—will only aggravate whatever harm to the public is attributed to such private behavior.

Alaska's population shift is still continuing, creating new political coalitions and majorities. There's no way of knowing whether the immigrants of the '80s will identify with the attitudes and convictions of the earlier Alaskans, or what form this identification might take.

But the evidence of the past eight years is noteworthy. Using Alaska as a sort of laboratory, the Ravin decision has put old myths to a practical test. What has been demonstrated, if any demonstration was needed, is that legalization of marijuana has not brought an era of pandemonium and debauchery to Alaska. People are leading their lives much as they did before. The sun rises and sets just as regularly in Alaska as it did before Ravin. In fact, the only discernible difference it has brought is that fewer Alaskans are now being punished for minding their own business.

Be lawful, not full of laws. More restrictions mean weaker people.…more laws mean more violators.…The people are rebellious when rulers meddle in their affairs.

—TAO TEH CHING 57, 75

Mike Dunham is a commercial writer currently working on the West Coast. He lived in Alaska from 1955 to 1982.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "When the Smoke Clears."

Show Comments (0)