Information Liberation

Incredible advances in computer and communications technology will open up new dimensions for personal freedom.

On a typical early morning in the year 1995 you arise eagerly to begin the day's activities. From your window comes the sound and the scent of the crashing surf, and it commands a view of miles of coastline. Your home is located atop a bluff on California's still sparsely populated Mendocino coast, far in time and space, it seems, from the noisy, crowded, polluted city.

Have you retired into this delightful new life? Inherited a large sum of money? Dropped out to pursue a simpler life? None of these. For you are still an executive in a large national company, still active in community affairs, still pursuing various hobbies, still socially engaged, and still able to enjoy the best in food, entertainment, and so on. The reason for the unusual and delightful turn of events is the technology around you—specifically, communications and information technology that, even in 1979, had begun to transform familiar lifestyles.

After breakfast you place a strange-looking phonograph record on a machine and watch instructions on your television for using a new analytical technique for your job. When it's over, you place another record on the machine and call your child in. She begins to watch an instructional program in English literature, complete with dramatizations of Shakespeare starring Lawrence Olivier and a tour through Stratford-on-Avon and the old Globe Theatre.

You proceed to another room in your home that is an office and sit down in front of another television-like screen that has a keyboard in front of it. You pick up the telephone, dial, and place the receiver down. On the screen appears your boss's face, live and in color. You have a discussion about business matters, during which you are able to display various printed and graphed pieces of information. Your work then continues at home during the morning. You are able to dictate and correct letters through your telephone, have face-to-face conversations with other colleagues, view a speech delivered the night before by the president of your company, and have your department's quarterly budget printed and on your boss's desk before lunch.

Later, you listen to and read on your screen mail that includes various voice and printed messages from all over the world. You also receive printed on a small device a facsimile of a signed, notarized document.

That afternoon your daughter, using a screen and keyboard similar to yours, takes an examination on the English literature material she watched previously. The exam is graded and the material she missed shown back to her on her screen as soon as the exam is over.

Finishing your work, you use your Visa card to dial into your bank account, and in approximately five minutes you accomplish the following:

• Pay for the examination your daughter took that afternoon.

• Transfer 100 ounces of gold from your local to your Swiss bank account.

• Pay your monthly Sears charge account bill.

• Make your monthly mortgage payment.

• Credit your daughter's weekly allowance.

The screen also shows you what your resulting bank balance is and, at your request, quotes the day's closing currency and commodity rates.

That evening, after a run on the beach and a swim, you participate in a community homeowners' association meeting while sitting at home before your television screen. You then watch a ballgame that was played that afternoon while you were working.

The lifestyle fantasized above could exist in 15 years, and it may not even require that the libertarian revolution succeed by then. For those of us who believe that the ever-growing scourge of lumbering government bureaucracy is the ultimate guarantee of our descent into a dark age, there is ample room for genuine optimism. This technology is moving so rapidly and with such success that it is likely the "lumbering scourge" is never going to know what hit it, much less be able to keep up.

PROMISING TECHNOLOGY

Information technology refers primarily to computers and communications. Advances in computers since their inception around World War II have been astounding. These advances can be expressed in terms of faster processing, increasing data storage, decreased power consumption, and decreased space requirements, all at less expense.

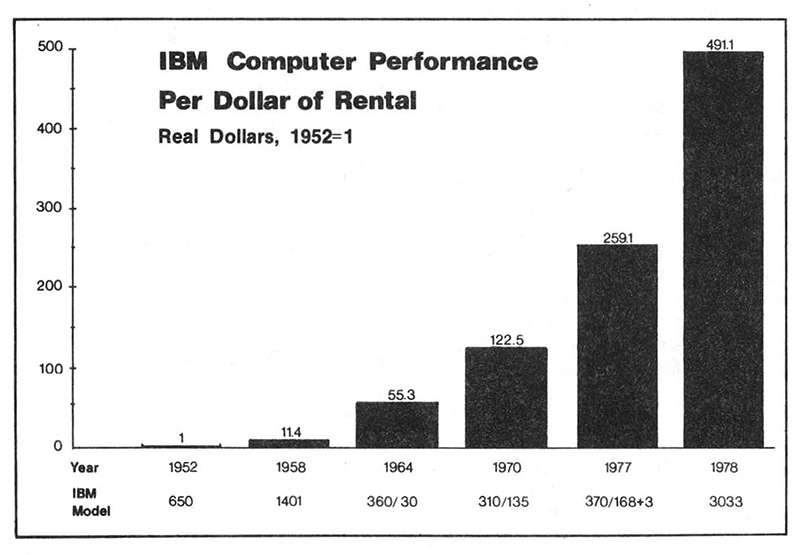

Using IBM large-scale computers as an example, the graph on page 32 shows that the ratio of processing capability to dollar of rental has increased almost 500 times since 1952. You can get almost 500 times the computing capability for the same dollar today on an IBM 3033 machine as you could in 1952 on an IBM 650. Also, that amount of memory requires about one-twentieth the space it would have in 1952*. The cost of a unit of solid-state computer power has declined an average of 35 percent per year since 1970 alone. John Opel, president of IBM, stated at the company's 1978 annual shareholders' meeting that IBM currently has on its order backlog more computer power than it has previously shipped in its entire history.

The immediate future for computers shows no less promise. Research is currently in the prototype stage on laser, bubble, and holographic memories and advancing rapidly in areas such as cryogenics (low-temperature technology). Robert Noyce, chairman of the Intel Corporation, sees "increased functional complexity [in large-scale computers] by a factor of over 2,000 during the next fifteen years."

In electronic communications, technological advancements of the same magnitude have taken place. One example is fiber-optic communications, where, using a laser source, a medium (such as a glass cable) can transmit hundreds of times more information than the same-size medium using current copper-wire technology. Dr. Philip Abelson, editor of Science magazine, writes that "this activity is leading to an era in which the electron, long the workhorse of the electronics revolution, will be supplanted by the even greater potential of the photon."

The technology is indeed dazzling. And a look at some of its applications will allow you to visualize more clearly the fantasy life described earlier.

VIDEO REVOLUTION

The technology is now available to produce a vinyl disk, like a long-playing phonograph record, capable of carrying a standard television signal and to produce a relatively inexpensive (about $600) device to view this through an ordinary TV set. The MCA Corporation (which owns Universal Studies, Universal Pictures, etc.) and Phillips, the Dutch electronic company, have already begun to market such a device. And RCA has also announced its own competing version of the "video-disk."

One video-disk will contain an hour's show, or about 100,000 images. This is equivalent to about 4 billion characters (letters or numbers) of information, or roughly 6,000 books, or 50,000 computer programs, or hundreds of hours of quadraphonic music. (Initially, video disks are being sold containing old television shows and movies; however, they would also be capable of carrying screen images of printed material.)

Video tape recorders have been on the market now for several years. The first was Sony's Betamax, and there is now another technology available. These machines cost in the neighborhood of $1,000 and allow you to tape a show off the air for later viewing. Old movies and TV shows are also available.

The implications of video tapes and disks are far-reaching. The industry estimates that two million players and recorders will be in homes by 1980. This could revolutionize the television industry, making broadcasting itself unnecessary except for live coverage of news and sports events. Certainly it will open up a whole new area of home entertainment, especially coupled with the perfection of large-screen TV viewing.

The consulting firm of Arthur D. Little estimates that movie theaters will be obsolete by 1985. When concerts, stage shows, art exhibits, etc., are available on video-disks and tapes, and a distribution system including retail outlets, mail order services, and loan libraries exists, people may be much less likely to undertake the necessary travel to see live entertainment. (Even today, professional sports have felt the effect of TV coverage on their gate receipts. The National Football League's "blackout" rule is a response to that problem.)

EXPANDING HORIZONS

Consider also that most existing human knowledge could be contained in a box of these video-disks, and what that might mean to book-loaning libraries and to education in general. Educational material could come on video-disks in a mixed format of reading matter and live action, as could newspapers and magazines. For those who are worried about saving the trees from the paper industry, this foreshadows a potentially drastic reduction in the need for paper.

Video recording will also reduce the need for travel and its associated energy resources. It will allow people enormous flexibility in where they live by offering greater access to education, information, and entertainment.

A growing body of opinion holds that the main cause of the sameness and mediocrity of today's television programming is the stultifying regulation by the FCC. Video-disks or tapes would not necessarily be immune from government regulation. As noted by David Levy, however, in his article on video-disks in REASON (Jan. 1977), "the regulatory restraint on a communications medium that differs only in technical detail from a phonograph record presumably will be minimal, since regulation of phonograph records is almost nonexistent." It would seem that video recording is about to make a large part of the "lumbering scourge" irrelevant.

Another area open to major technological innovation over the next few years is message delivery. Messages can be divided into three categories with regard to electronic transmission:

• Transmission that is not concerned with the format of the message and can use a video screen or a teletype.

• "Facsimile transmission" that communicates an exact copy of something like a document or a signature.

• Electronic funds transfer (EFT), which refers to transmission of any type of financial information—such as payment of bills, consumer charges, and checks—and which accounts for over 70 percent of all first-class mail.

BESTING THE POST OFFICE

No one has to be reminded how efficiently the government runs the Postal Service. Since World War II, we have seen the cost of less and less service on a first-class letter go from 2 cents to 5 cents to 10 cents to 13 cents and now to 15 cents, and they are also proposing cutting back service to five days a week. For the first time in a hundred years there are again challenges in the courts to the federal government's first-class postal monopoly.

In 1976, a congressional commission, having undertaken a six-month study of the postal service, concluded that its future might be bleak unless they joined at once with private enterprise to use electronic communications for mail. At the same time a National Academy of Sciences panel observed: "Time is running out for the Postal Service. While it delays its entry into electronic message services, developments by private firms are sure to proceed, possibly foreclosing any opportunity…to move into the field in any meaningful way." A George Washington University study has concluded that by 1982 privately run electronic systems will be well ahead of any possible postal service system.

The USPS is currently spending less than one-fifth of one percent of its annual budget on research and development. The following rather startling comment by Postmaster General Frank Bailar appeared in the May 10, 1977, Wall Street Journal: "I don't see any reason why the government ought to be in a business which private industry is willing and able to take care of."

Electronic communications developments mean the traditional Postal Service is going to have less volume and be less important. (Postal Union leader James La Penta sees "a conspiracy to turn the mails back to private enterprise.")

Whatever the Postal Service does will probably be irrelevant. It is likely that we will all soon be the beneficiaries of privately supplied and vastly improved electronic message services, rather than our current "hopelessly outmoded system of people walking around with bags of processed wood pulp covered with black marks."

ELECTRONIC PRIVACY

Electronic funds transfer generally refers to the electronic transmission of data relating to financial transactions. Today you can see various aspects of EFT—for example, in teller machines that are remote from bank branches, systems that wire funds between banks, and department store cash registers that automatically debit your charge account when you make a purchase.

The predictions for EFT are that, someday, terminals connected to a central computer at your bank will automatically deposit your paycheck, transfer funds from your account to the accounts of those from whom you obtain goods and services, and (probably) also deduct your taxes. Technology has made this concept feasible for many years. In 1974, IBM and the Bank of America collaborated with a number of merchants and employers in Columbus, Ohio, to run a pilot test of such a system. Personal Bankamericards were used as the trigger for all transactions.

Well, any red-blooded libertarian probably cringes in horror at the prospect EFT presents for snooping and control by the "lumbering scourge." Consider also, however, the opportunity this technology offers for circumventing government control through private economic systems. The proliferation of trade clubs and other stateless economic systems certainly demonstrates people's penchant for this approach. The major problem now is administering the massive amount of paperwork these systems generate. Modern data-processing technology offers the solution to this problem and to the problem of privacy.

The science of cryptology (secret codes) has developed techniques today for protecting storage and transmission of data with codes that are literally unbreakable. This means that, conceivably, networks of users generating financial transactions could be totally protected from government snooping and intervention. Such private systems could become the way that more and more Americans simply avoid participating in the depression/inflation economy. In the worst circumstances, private economic systems using EFT could also become the vehicle for recovery from an ultimate economic collapse.

SMALL IS EFFICIENT

A recent study at the University of Southern California proposed small regional offices using computers and communications for a large Los Angeles-based insurance company instead of their current large central office building. After studying the various alternatives, it was found most economically feasible to disperse the company into 18 offices with 25-30 persons in each, spread throughout southern California. The factors considered included the time and cost of commuting downtown, telephone expenses, and costs incurred by customers for personal visits.

"Distributed data processing" is probably the hottest concept in the data-processing industry today. It refers to distributing data storage and processing capability away from large central sites to the end user. The proliferation of this approach could have a more far-reaching effect on work habits and therefore on lifestyles of the future than any of the other technological developments mentioned so far.

The data communications industry, a $250 million industry in 1968, was estimated by Datamation magazine to have been $7.1 billion in 1978. Texas Instruments currently has one computer terminal for every 20 employees and has plans for a terminal for every 10. And according to the previously mentioned study by Arthur D. Little, "Our current rate of technological advance makes it almost certain that it will be economically feasible to install electronic terminals in essentially all residences and places of business in the US as early as the late 1980s."

Consider the implications of armies of clerks working in or near their homes, using only a fraction of the amount of energy, paper, and other resources they currently consume. This could include most of the people who work in banks, insurance companies, distribution industries, credit organizations, law firms, accounting firms, writing and publishing companies, and many others. Consider the potential reduction of the problems of urban planning, transportation, energy consumption, forest conservation, and the vastly increased freedom of individual choice of where to live.

With the reduced need for urbanization flowing from vastly superior communications, small self-contained communities would be much more likely to flourish. The political implications of this could be more local control, more isolation from centralized bureaucracy, a greater social sense of community, and consequently improved human relationships and a greater concentration on the values of individualism.

Technology is certainly no guarantee of freedom, particularly if the current cultural trends toward totalitarianism continue. It is, however, becoming a powerful force away from bureaucratic control. It is presenting solutions to the increasingly complex problems of our society, which previously were only excuses for more government control. It offers potential methods for avoiding creeping totalitarianism and could, in fact, be the road to recovery in the event of total economic collapse.

Most importantly, it offers a glimpse of the vast richness of possible lifestyles of the future. It must surely stimulate childlike wonder and joyful expectation in all of us.

Michael Anzis is a management consultant with Arthur Young & Co., where he specializes in electronic data processing. His 11 years' experience in the field includes over 7 with IBM.

*Technology rolls along despite authors who delay in submitting articles. As of February 1979 IBM has introduced the first models of a new line of computers which use an advanced technology and surpass the price/performance of the 3000 series.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Information Liberation."

Show Comments (0)