Federal Reserve Defers to Donald Trump by Cutting Interest Rates by 25 Points

The Federal Open Market Committee lowered the federal funds rate for the third meeting in a row despite elevated inflation.

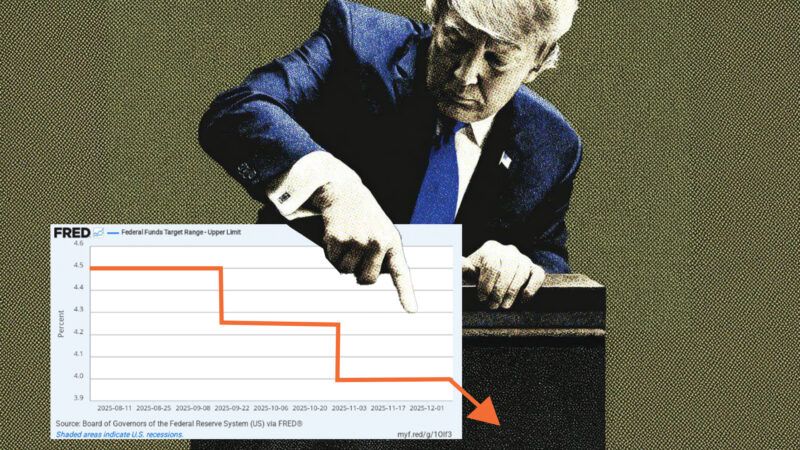

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, voted to lower its federal funds rate—the interest rate that banks charge each other to borrow overnight and the cost of credit—by 25 basis points on Wednesday. This is the Fed's third rate cut in as many months and the lowest federal funds rate in three years.

The move comes amid lackluster employment numbers and the Supreme Court hearing Trump v. Slaughter, a case in which it is likely to overturn Humphrey's Executor, a decision that would likely grant the president license not only to remove executive agency bureaucrats but to replace the Fed's Board of Governors. In view of these pressures, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), led by Fed Chair Jerome Powell, may be preemptively catering to President Donald Trump's calls to lower interest rates in a bid to avoid replacement if and when Humphrey's Executor is overturned.

Trump has been egging the FOMC, the Fed's key policymaking body, to lower rates since this summer. In June, the president sent Powell a letter saying, "we should be paying 1% Interest, or better!" In late July, with year-over-year inflation at 2.6 percent, well above the Fed's 2 percent target, Powell and all but two members of the 12-member FOMC wisely held the fed funds target constant. However, in mid-September, the Fed decreased the fed funds rate by 25 basis points, lowering the upper bound rate from 4.5 percent to 4.25 percent.

Stephen Miran, nominated by Trump and confirmed as a member of the Fed's Board of Governors in September, shortly before the fed funds announcement, dissented. Per the FOMC's official statement, Miran "preferred to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point."

At the end of October, the FOMC lowered the fed funds rate by another 25 basis points, leaving the upper bound at 4.0 percent. Miran again dissented, preferring a 50 basis point decrease in the federal funds rate. Miran's dissent was juxtaposed by Jeffrey Schmid, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, who voted against lowering the rate at all.

On Wednesday, Miran yet again objected to the FOMC's decision to lower the fed funds rate by 25 basis points, preferring a 50-basis point drop. Schmid also dissented the same way he had in October, voting for no change whatsoever. On Wednesday, Schmid was joined in his opposition to rate cuts by Austan Goolsbee, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. The Wall Street Journal notes that this is "the first time in six years that three officials cast dissents."

But two members of the FOMC voting against further rate cuts should not be surprising: Year-over-year inflation has been stubbornly increasing since April. The Consumer Price Index, the most common inflation metric and the one used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, rose from 2.3 percent in April to 3 percent in September. Meanwhile, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index, the Federal Reserve's preferred inflation measure, increased from 2.3 percent to 2.8 percent. At the same time, the unemployment rate has increased from 4.2 percent to 4.4 percent, while the labor force participation rate decreased slightly from 62.6 percent to 62.4 percent.

Peter C. Earle, director of economics and economic freedom at the American Institute for Economic Research, tells Reason that the Fed's decision to continue lowering interest rates in the face of persistently elevated inflation signals that "it has chosen to prioritize labor market softness over the purchasing power of the dollar and broader affordability concerns." Earle says the latest cut is risky, but defensible, as "inflation projections for this year and 2026 have been revised lower, [while] unemployment forecasts remain steady, and private hiring data suggest a labor market that's cooling." More troubling than the decision itself is the phenomenon of "members aligning their votes with rapid, deeper cuts in line with what the President has expressed a desire for."

Earle predicts that, "if presidential discretion over the Fed's Board of Governors expands in the wake of Humphrey's Executor [being overturned]…the result would be a Federal Reserve more vulnerable to serving the immediate priorities of the executive branch rather than maintaining consistent rules, stable money, and a predictable policy environment." Such central bank would "weaken the dollar and undermine long-term investment planning," warns Earle.

Show Comments (77)