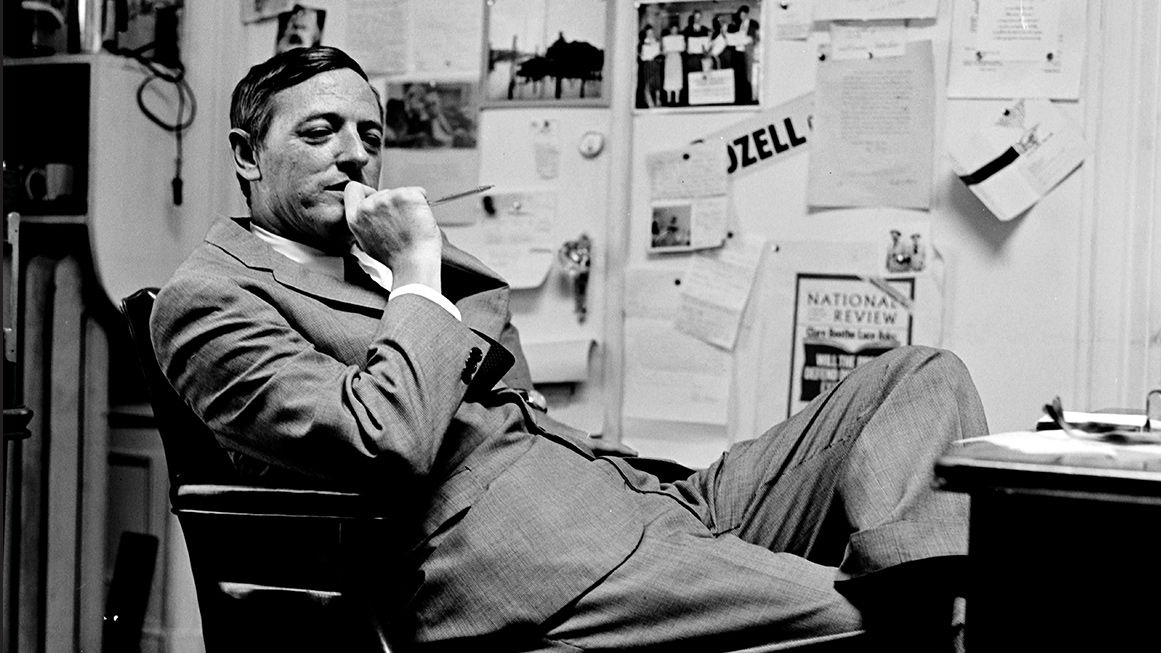

What Would Bill Buckley Do?

The National Review founder's flexible approach to politics defined conservatism as we know it.

How would William F. Buckley Jr., born 100 years ago in November, feel about the Trumpian takeover of the American conservative movement? Because Buckley lacked a solidly reasoned ideology, that question turns out to be almost impossible to answer with assurance.

The National Review founder identified at times as both a libertarian and an individualist, helping to found a group then called the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (which now goes by the more ideologically null Intercollegiate Studies Institute) and subtitling one of his essay collections Reflections of a Libertarian Journalist. He also defended the far-from-libertarian dictators Francisco Franco and Augusto Pinochet. He was a tough-on-crime proponent of the death penalty but a supporter of the legalization of drugs and gambling. He was a vehement anti-communist willing to sacrifice freedom at home in order to defeat what he saw as a greater threat to freedom abroad.

Under his leadership, National Review criticized the so-called imperial presidency. In a long article laying out an agenda for the 1990s, Buckley himself warned about "executive usurpation" of Congress' rightful powers. "A strong executive can be a necessary, galvanizing force," he wrote. "But the executive's authority cannot be supreme, let alone unchallenged."

The same article argued against tariffs on both practical grounds (they make the country that levies them less competitive) and humanitarian ones. "To mobilize against the economic ascendancy of poor nations by attempting to exclude their products from the home market is inhibiting not only to the United States consumer but also to prospective economic growth in lands inhabited by—fellow human beings," he wrote. "Tariffs are a form of economic warfare, and it is fortunate that the arguments against protectionism blend prudential and moral considerations."

None of this sounds like a writer who would have been eager to climb aboard the MAGA train. President Donald Trump, after all, is fiercely opposed to free trade, harbors an undisguised desire to concentrate power in his own hands, and cares little for the rule of law if it foils his perceived prerogatives. Yet Buckley was more than willing to twist himself into rhetorical pretzels in order to excuse the lapses of people—Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R–Wisc.) during the 1950s Red Scare, President Richard Nixon during Watergate, even the notoriously corrupt lawyer Roy Cohn—whom he saw as members of his team fighting the perfidies of the left. "But he fights," the ubiquitous defense of Trump over the last 10 years, may well have been the decisive criterion for Buckley, were he alive today.

Attempting to nail down Buckley's philosophical commitments is a fool's errand, because Buckley, unlike some of the other figures associated with his publication, was not an ideologue. "Bill's strength and weakness as a political thinker was that he was reluctant to generalize, to ascend from particular conclusions to universal principles," wrote Claremont Review of Books editor Charles Kesler shortly after Buckley's death. "He preferred to reason prudentially, deliberatively, one case at a time."

One of Buckley's legacies was to create not just a magazine but a movement where a variety of perspectives were welcome. Conservatives in the second half of the 20th century were "so badly outnumbered," writes his biographer, Sam Tanenhaus, "they all needed to be able to say what they thought in words of their own choosing. He would not enforce unanimity or expect it." He never imposed a party line on National Review, and he granted himself the same liberty. The word conservative could mean a dizzying array of things, and Buckley embodied virtually all of them at one point or another.

Military Interventionism and Race

Take foreign policy. Buckley's earliest commitments, inherited from his father, were isolationist: Charles Lindbergh was a hero to the family, and a teenage Buckley was an "ardent member" of the America First Committee, which opposed America's entrance into World War II.

That view became less tenable following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Buckley served on the homefront during the war and later did a two-year stint with the CIA. Tensions with the Soviet Union cemented his change of perspective: Once a believer that American interests were best served by keeping out of other countries' conflicts, Buckley became a dogged Cold Warrior who once went so far as to publish fabricated government documents in an effort to undermine the Pentagon Papers and shore up public support for Vietnam.

The stakes of the conflict with communism were so existential, Buckley thought, that limited government had to take a back seat. Conservatives would have to "accept Big Government for the duration—for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged except through the instrument of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores," he wrote. "To beat the Soviet Union, we must, to an extent, imitate the Soviet Union" by embracing military conscription and onerous taxation to support a military buildup. These views were hardly libertarian, even if they reflected a desire to see "the free world" win.

Buckley was willing to change his position when conditions changed. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, he continued to support a hawkish (now usually described as "neoconservative") foreign policy and defended President George W. Bush's invasion of Iraq. But he later admitted the war had been a mistake and expressed regret over a National Review cover feature that described right-of-center opponents of the war, such as the columnist Robert Novak, as "unpatriotic conservatives."

Buckley's stance on race relations also evolved over time. In 1957, he penned a now-infamous unsigned editorial, "Why the South Must Prevail," in which he advanced the horrendously illiberal view that "the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically…because, for the time being, it is the advanced race." As Tanenhaus explains, "These were the beliefs of the white South, which Bill Buckley grew up accepting as ideal in a civilized and harmoniously religious culture. Both his parents came from segregated regions whose social life was shaped by the rigid formations of caste."

Within a few years, though, Buckley "was beginning to harbor doubts about legal segregation, a practice he had accepted without question his entire life," the historian Alvin Felzenberg wrote in 2017. In 1968, he lambasted the Alabama segregationist George Wallace on his TV show Firing Line. In 1969, he went on an eye-opening tour of the "black American ghetto" sponsored by the National Urban League and, decades before Barack Obama's election, concluded that America needed a black president.

The same person who had once defended South Africa's system of apartheid began to object to its denial of voting rights to black people. The same person who once denounced Martin Luther King Jr. as a law-breaking militant went on to favorably invoke the slain civil rights leader in his syndicated column. Reflecting on National Review's early commentary on racial issues, he later said, "I rather wish we had taken a more transcendent position."

Speech and Academic Freedom

Buckley's changing positions were not always caused by his views maturing in response to new information. He sometimes oscillated between contradictory positions merely for political convenience.

For example, Buckley couldn't seem to decide where he stood on free speech. In high school, he gave a well-regarded speech defending his hero Lindbergh's outspoken opposition to U.S. involvement in the war. "Is every American not having the popular point of view a traitor to his country?" Buckley asked. "Opposition is everyone's right and a democracy cannot have too much of it." But that stock defense of the right to political dissent went only so far. After Time published an article criticizing Lindbergh, young Buckley wrote to the magazine, using an alias, to inform the editors he had reported them to the FBI for "stirring national unrest and damaging the cause of unity."

Buckley first broke into the national consciousness with his 1951 book God and Man at Yale, which was essentially a long attack on the academic freedom of what he saw as the dangerously liberal faculty at his alma mater. Under the influence of the cantankerous Yale professor Willmoore Kendall, Buckley argued that college instructors should be constrained by the orthodoxy of those who foot the bills—namely, parents and alumni—and thus proscribed from promoting atheism or left-wing economics.

He would later object to the idea that college students have the right to host a lecture on campus by a member of the Communist Party. Hearing from such a person would be "reprehensible and degrading," Buckley insisted. The point of education, he seemed to think, was to transmit substantive truths (as determined by those who just so happened to see things the way he did) rather than to teach pupils to think for themselves.

For all his wavering on intellectual freedom, Buckley was a lifelong defender of many of America's liberal founding principles. In one 1979 speech, he described the difference between Chinese- and Russian-style communism this way: "In the Soviet Union there is an infinitely long list of that which one is forbidden to do. In China, it works the other way. One may do nothing except those things which one is explicitly permitted to do." What makes the United States special, Buckley concluded, is that our Bill of Rights "is essentially a list of prohibitions, but it is a list of things that the government cannot do to the people."

"What a huge distinction—a majestic distinction," he said. "It grew out of a long, empirical journey, the eternal spark of which traces back to Bethlehem, to that star that magnified man beyond the powers of the emperors and gold seekers and legions of soldiers and slaves. A star that implanted in each one of us that essence that separates us from the beasts and tells us that we are made in the image of God and were meant to be free."

Buckley's inconsistent application of such principles is frustrating from a libertarian perspective, but it explains his success as a movement builder. His magnanimity and flexibility brought many strands and strains of conservatism together. He acted as the St. Paul of the American right, willing to be all things to all people if that's what he thought it would take to reach them.

Reach people he did. During his quixotic 1965 campaign for New York City mayor, a senior editor at The New York Times supposedly "confessed that he had taken to dispatching different reporters to Buckley's press conferences" after they kept coming back saying they had decided to vote for him. In politics, then as now, charm matters more than intellectual consistency.

Show Comments (22)