The U.N. Has Now Held 30 Climate Change Conferences That Have Accomplished Almost Nothing

COP30 in Brazil just ended and was more of the same.

The United Nations' 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stuttered to its end in Belem, Brazil, over the weekend. From the point of view of climate activists and poor countries demanding that rich countries supply them with hundreds of billions of dollars in climate change handouts, COP30 was largely a bust. In addition, the chief activist goal for a commitment to a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels by a date certain was nowhere to be seen in the conference's final Global Mutirão decision.

COP30 convened 10 years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, in which signatory countries committed to "holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels." In pursuit of that goal, signatories were supposed to increase their commitments in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) to cut their emissions of greenhouse gases, chiefly carbon dioxide from burning coal, oil, and natural gas, which are contributing to the rise in global average temperatures.

The Global Mutirão notes that achieving the Paris Agreement's limit of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions of 43 percent by 2030 and 60 percent by 2035 relative to the 2019 level and reaching net zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. That's not going to happen.

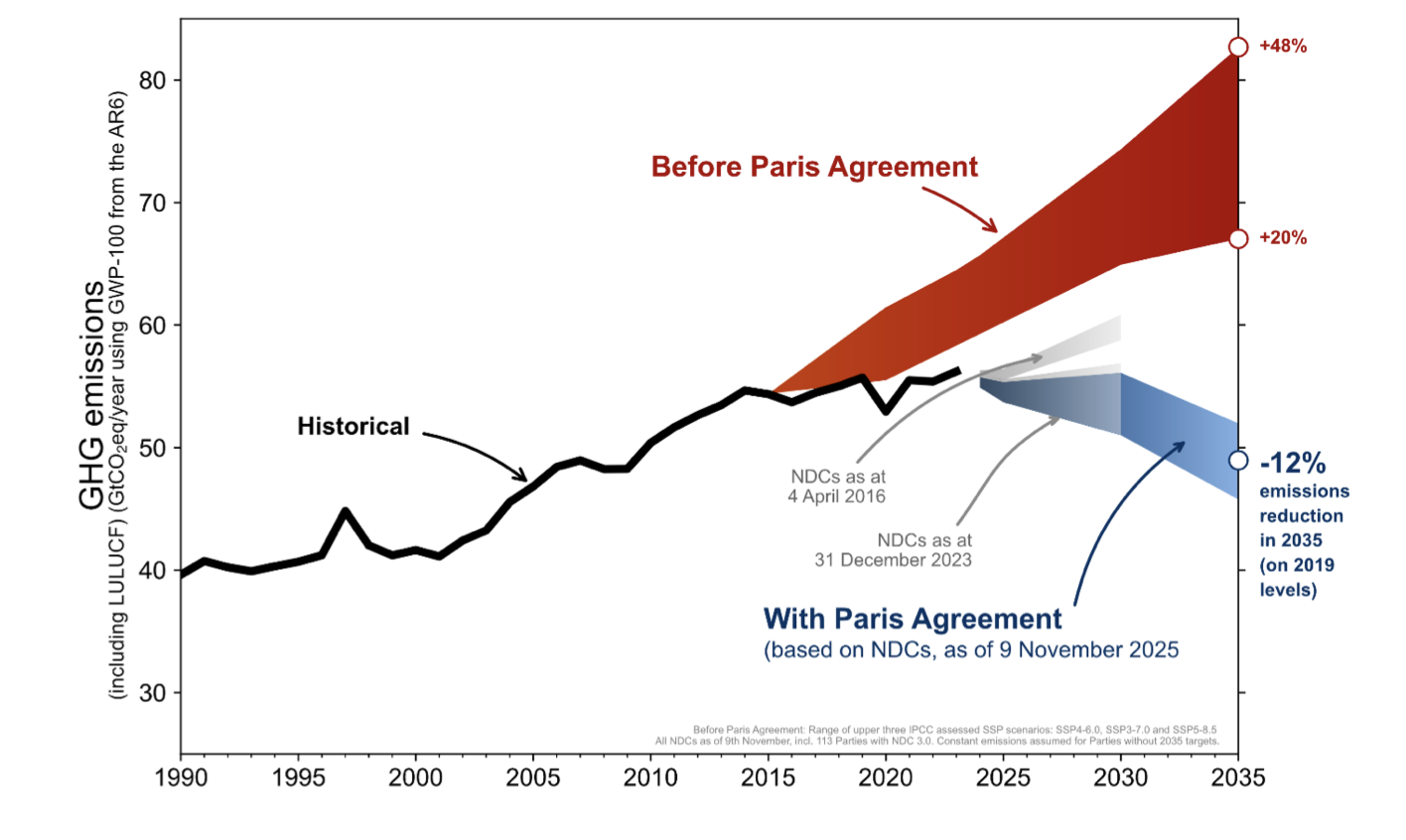

The U.N. Environment Programme calculates that if countries actually kept their NDC promises, global emissions would only fall by between 12 and 15 percent by 2035 relative to their 2019 levels, and that those reductions would shrink further to between 9 and 11 percent if the U.S.'s NDC is not counted. And it shouldn't be counted since President Donald Trump issued an executive order on his first day in office to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement. Also, the U.S. sent no official representatives to COP30.

The Global Mutirão "urgently advances" efforts to scale up climate action funding from rich countries to poor ones to $1.3 trillion per year by 2035. But total international aid from official donors fell by 7.1 percent to just over $212 billion last year. Even taking into account contributions from multilateral financial institutions and making generous assumptions that include "mobilizing" private investments, climate finance for developing countries was around $116 billion in 2022.

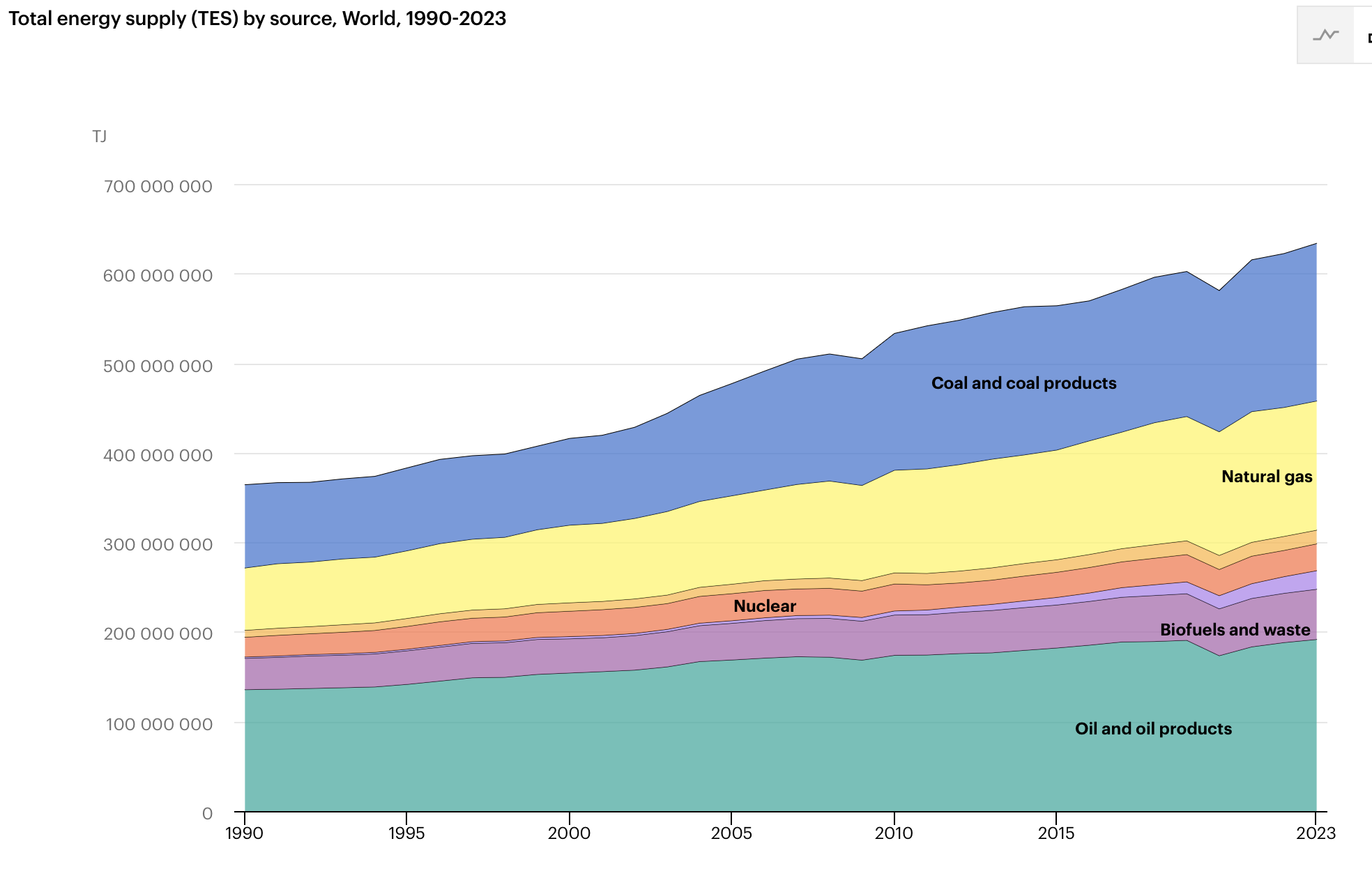

On the other hand, the International Energy Agency reports that private commercial investments in no- and low-carbon energy technologies are now outstripping those in fossil fuels. Even so, fossil fuels continue to provide the bulk of global primary energy production.

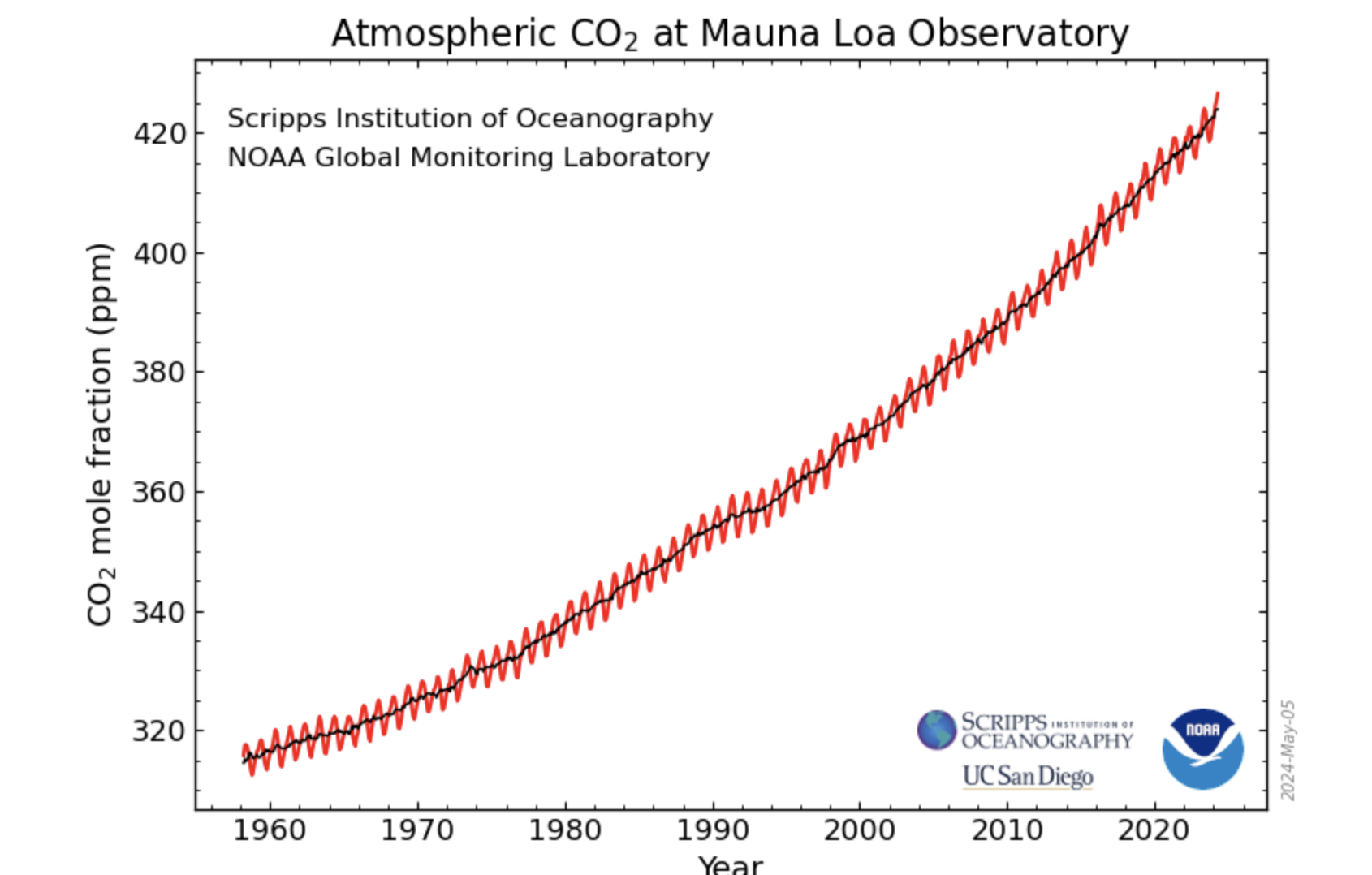

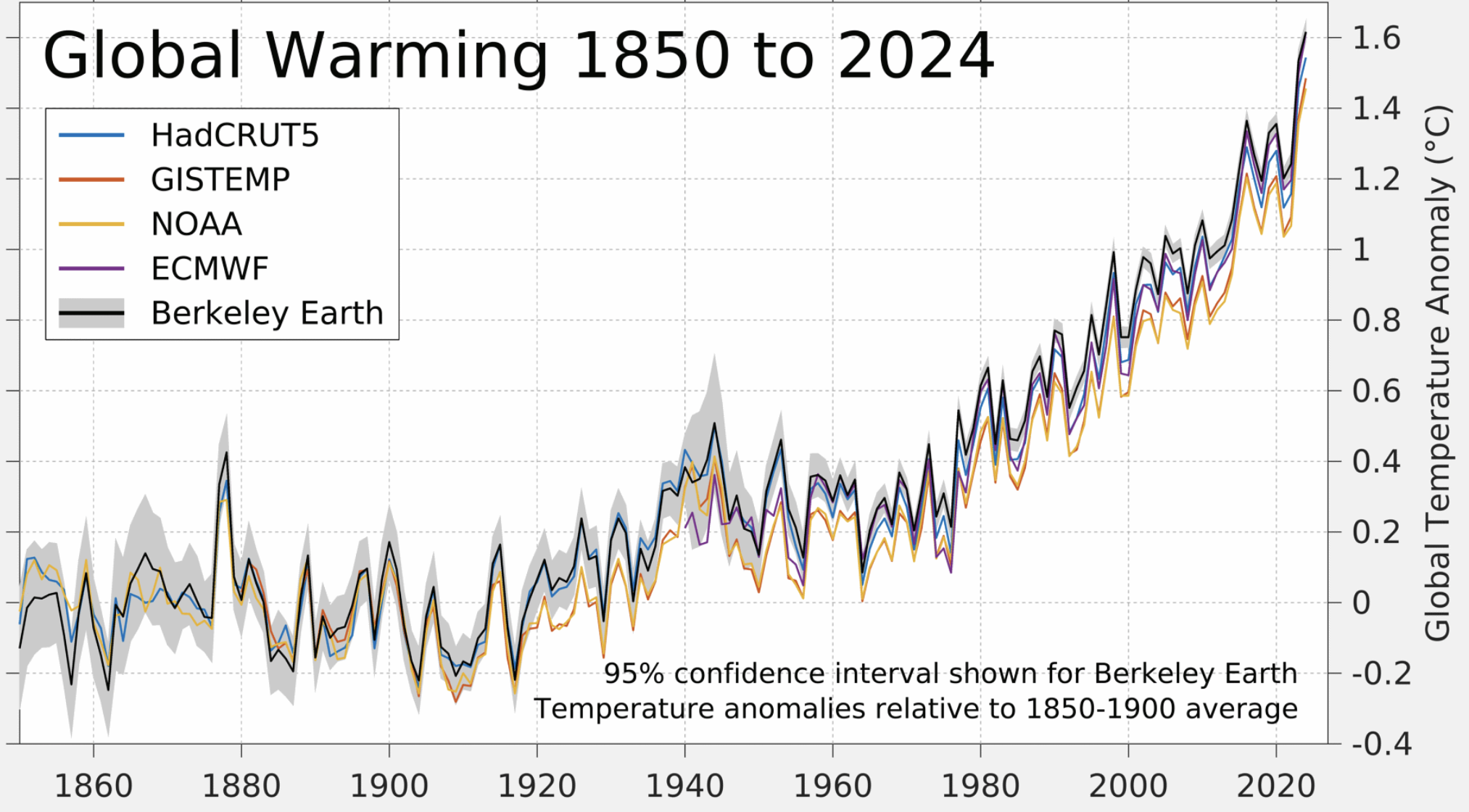

Despite more than 30 years of climate change negotiations, carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere continue to rise as concomitantly do global average temperatures.

The increase in carbon dioxide emissions in 2024 was the highest single-year record and last year was also the warmest in the instrumental record.

American Enterprise Institute senior science and technology fellow Roger Pielke Jr. points out that in the Global Mutirão decision, the United Nations climate change negotiators are taking unwarranted credit for lower projected temperatures in 2100.

In their "celebration of the 10-year anniversary of the Paris Agreement," the negotiators claim that "significant collective progress towards the Paris Agreement temperature goal has been made, from an expected global temperature increase of more than 4 °C according to some projections prior to the adoption of the Agreement to an increase in the range of 2.3–2.5 °C and a bending of the emission curve based on the full implementation of the latest nationally determined contributions."

In support of this alleged achievement, the UNFCCC secretariat supplied this illustration.

The "before" trend in the chart is based on worst-case greenhouse gas emissions scenarios that have long been known to be highly implausible, not least because they projected that the world would be burning six times more coal by 2100 than now.

"The differences between the two forecasts reflect the simple fact that the red cone represents erroneous projections, while the blue cone represents a more updated understanding of where we are headed," explains Pielke over at his Substack. "The story here is that extreme emissions projections were well off track, and real-world data pointed to a much more moderate future. Spinning that course correction as the result of policy success is not supported by the evidence."

In fact, Pielke and his colleagues, using more plausible emissions scenarios, projected in 2022 that global average temperatures would rise above the preindustrial baseline (1850-1900) to "between 2 °C and 3 °C of warming by 2100, with a median of 2.2 °C." In its COP30 Global Mutirão Decision, the U.N. climate change negotiators now basically agree with the projections made by Pielke and his colleagues.

"Even though projections of future climate change have moderated considerably in recent years," correctly observes Pielke, "the human influence on climate remains real and poses risks to our collective future." More than 30 years on, U.N. climate change negotiations have not done much to ameliorate those risks.

Show Comments (58)