You Can Thank This Ohio Klansman for Expanding Your Freedom of Speech

Brandenburg v. Ohio established the "imminent lawless action" standard. More than 50 years later, partisans keep trying to apply it selectively.

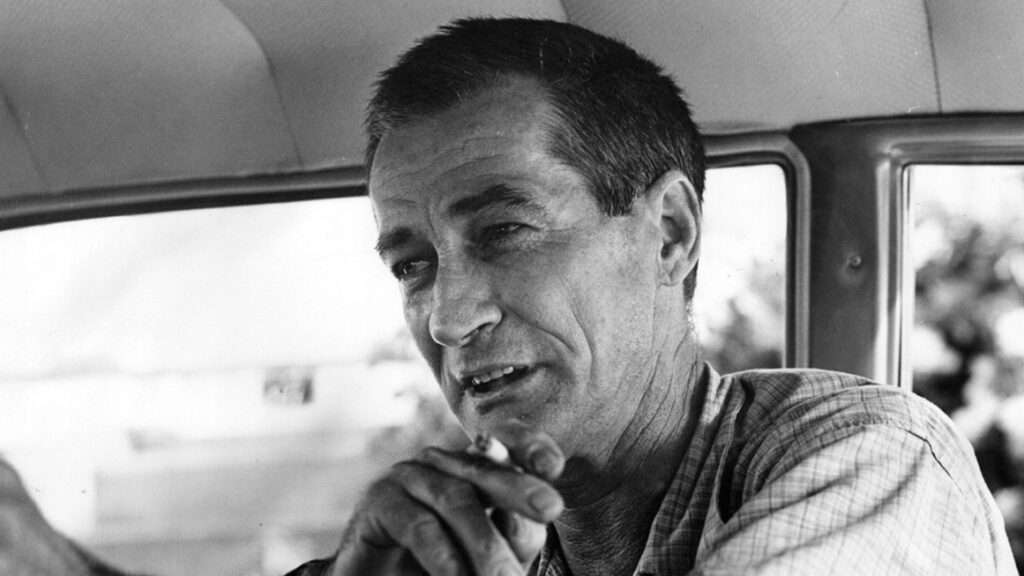

On a Sunday evening in June 1964, about 20 men gathered at a farm in Ohio for a Ku Klux Klan rally. The event featured a cross burning, some stray racist and antisemitic remarks, and a short, desultory speech by a TV repairman named Clarence Brandenburg. The meeting was so small and inconspicuous that no one aside from the participants would have noticed it if Brandenburg had not invited a local television station to document his publicity stunt. But thanks to footage shot by a cameraman at Cincinnati's NBC affiliate, the rally triggered a police investigation that resulted in criminal charges against Brandenburg.

Five years later, that case produced a Supreme Court ruling that still reverberates in debates about the limits of free speech. The Court's 1969 decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio established a new, stricter constitutional test for government restrictions on provocative rhetoric. It was a boon to controversial speakers across the political spectrum. But Brandenburg's beneficiaries often ignore its strictures when confronted by opinions they abhor.

When President Donald Trump's critics said he should be held criminally or civilly liable for the speech he gave before the 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol, for example, they had to choose between contending with Brandenburg and ignoring it. Trump himself faced the same choice when he launched his deportation campaign against international students with anti-Israel views.

In those cases, Democrats and Republicans tended to switch sides on the question of whether inflammatory speech should be punished. Similarly, progressives who defy Brandenburg by advocating restrictions on "hate speech" are apt to change their tune when the subject is lawsuits against Black Lives Matter activists, while conservatives who oppose the former may nevertheless support the latter.

These inconsistencies are shortsighted as well as unprincipled. If freedom of speech hinges on the speaker's viewpoint, ideology, or political affiliation, no one can rely on it.

The Brandenburg test instead focuses on the speaker's intent and the probable consequences of his conduct, allowing punishment only when speech is both "directed" at inciting "imminent lawless action" and "likely" to have that effect. That standard is imperfect, but it provides much more dependable protection than the "clear and present danger" test it replaced.

'There Might Have To Be Some Revengeance'

Brandenburg set the stage for the case that bears his name by inviting WLWT to cover a "secret" KKK meeting, provided the TV station promised not to alert local police or the FBI. Reporter Al Leonard and cameraman Eugene Neuber got the assignment, which they approached with some trepidation. Neuber later testified that he and Leonard brought guns with them when they drove to meet the Klansmen who would take them to the rally site, although the newsmen ended up leaving the weapons under the front seat of their car.

Neuber's footage of the rally showed a dozen hooded men, several of whom were carrying guns, gathered around a large wooden cross that they set on fire. "Most of the words uttered during the scene were incomprehensible when the film was projected," the Supreme Court would later note, "but scattered phrases could be understood."

The level of discourse was about what you might expect at a Klan rally. "This is what we are going to do to the niggers," someone said. Other comments suggested that the attendees aspired to "save America," recover "our states' rights," "go back to constitutional betterment," achieve "freedom for the whites," "bury the niggers," and "send the Jews back to Israel."

It was never clear who exactly said those things. But Brandenburg was eventually fingered as the guy in a red hood who briefly addressed what he described as an "organizers' meeting." He bragged that the Klan had "hundreds of members" in Ohio, which he claimed made it the largest organization in the state. He described a fanciful plan for a July 4 march that supposedly would bring 400,000 Klansmen to the nation's capital. "We're not a revengent organization," he said, "but if our president, our Congress, our Supreme Court continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it's possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken."

Neuber also shot an indoor scene in which Brandenburg, accompanied by five other hooded men, gave essentially the same speech. This time, he did not mention "revengeance," but he gave a hint of his demographic agenda. "Personally," he said, "I believe the nigger should be returned to Africa, the Jew returned to Israel."

Brandenburg's defense attorney, Peter Outcalt, would later describe his client's organization as "a band of silly little men in bedsheets." Allen Brown, the Cincinnati civil liberties lawyer who represented the two-bit bigot at the Supreme Court, likewise dismissed Brandenburg and his cronies as "paltry unknowns, rather silly characters" who had "yelled some stupid and rather senseless slogans" before Brandenburg gave a speech full of "hyperbole" that was "self-evidently stupid and silly."

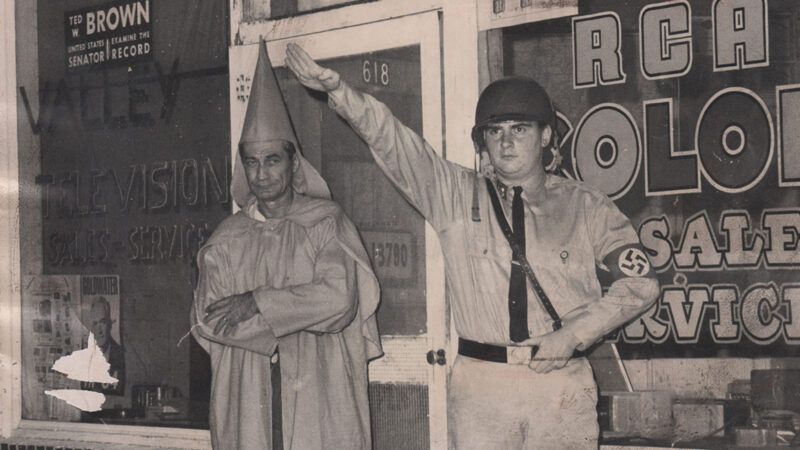

The police took a different view. After some of Neuber's footage aired on WLWT and other NBC stations, they launched a two-month investigation to identify the man in the red hood. In August 1964, they arrested Brandenburg at his TV repair shop in Arlington Heights, a Cincinnati suburb, and charged him with violating Ohio's ban on "criminal syndicalism." Searches of his business and home turned up a red hood with eye holes, three loaded guns, a briefcase full of KKK literature, a list of Klansmen in the Cincinnati area, and what The Cincinnati Enquirer described as "periodicals dealing with militant right-wing organizations."

Brandenburg insisted he had been framed. "I am an imperial officer in the national KKK and proud of it," he told the Enquirer. But he denied participating in the rally. "Jewism and communism are back of all this," he averred. He also blamed an estranged ally: William F. Miller, president of the National Association for the Advancement of White People.

Despite his falling-out with Miller, Brandenburg presented himself as tolerant and broad-minded, open to alliances with any "white Christian American" who hated the right minorities. "The only way the white people are going to get back in power in this country is to get together," he told The Daily Tar Heel. "I don't care if they belong to the Nazi Party, or the Birch Society, or what, but it's time the right-wing people got together."

That article described Brandenburg as head of "the Cincinnati chapter of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan." But in an interview with Cincinnati Enquirer reporter Bob Webb around the same time, Brandenburg denied that he was active in the KKK. "I have never been initiated into the Klan," he told Webb, contradicting what he had said immediately after his arrest. "I surely don't have the four degrees in the Klan necessary to be an officer….This whole business of me being a Klan officer was rigged." He described the red hood that police said they found in his shop as "a plant," saying, "I don't know how it got into my place."

When Webb noted that a recent photograph showed Brandenburg wearing a gold robe and hood while standing outside his business next to a local neo-Nazi, Brandenburg defended that fashion choice. "My wife made that gold robe for me," he said. "There's no law against wearing something like that."

According to the cops, however, there was a law against the words Brandenburg had spoken at the Klan rally. They cited Ohio's criminal syndicalism statute, which legislators had approved in 1919, around the same time that 19 other states and two territories enacted similar laws.

Although those legislators were worried about anarchists and communists, the language of the statute was broad enough to cover much of the radical right too. The law made it a felony to "advocate or teach the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform." It covered printed material as well as spoken words, and it extended to anyone who "voluntarily assemble[s]" with a group engaged in such advocacy.

Brandenburg's trial, which was repeatedly delayed, began in November 1966, two years after his indictment. It focused on two issues: Was Brandenburg the man who gave the "revengeance" speech, and did those remarks amount to criminal syndicalism? Outcalt, Brandenburg's lawyer, tried to cast doubt on both points. But he offered no objection to the jury instructions, which mirrored the terms of the statute, and he never suggested the law violated the First Amendment.

The jurors, who watched Neuber's footage during the trial and again while mulling their verdict, convicted Brandenburg after deliberating for about three hours. He was fined $1,000 (nearly $10,000 in current dollars) and sentenced to a prison term of one to 10 years. The Ohio Supreme Court rejected his appeal without issuing an opinion, saying only that "no substantial constitutional question exists herein."

'Here We Come, First Amendment'

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Ohio disagreed. It recruited Brown to represent Brandenburg, who consented after expressing some reluctance about letting a Jew speak for him.

Unlike Outcalt, Brown mounted a frontal assault on the constitutionality of Ohio's law. "On its face," the statute "thrusts itself into the First Amendment," he told the U.S. Supreme Court during oral argument in February 1969. "It announces boldly, 'Here we come, First Amendment.'" Brown emphasized that the law made no attempt to distinguish "mere abstract teaching and advocacy" from the sort of speech that poses a "clear and present danger" to public safety or national security.

The Supreme Court first enunciated that test for incitement in the 1919 case Schenck v. United States, which involved two Socialist Party leaders who had been convicted of violating the Espionage Act by distributing anti-draft pamphlets during World War I. The justices unanimously upheld those convictions, saying they were justified by the wartime context.

"We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights," Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote for the Court. "The character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic."

Schenck today is remembered mostly for that analogy, which would-be censors frequently deploy against speech they view as intolerably dangerous. But the false-alarm scenario merely illustrated the point that speech can be criminalized in certain contexts. The question, Holmes said, is "whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right."

Inconveniently for Brandenburg and Brown, the Court extended that logic six years later in Gitlow v. New York, which upheld a Socialist's conviction for "advocacy of criminal anarchy," defined as "the doctrine that organized government should be overthrown by force or violence" or any other "unlawful means." Citing Schenck, the majority declared that the government may punish speech when "its natural tendency and probable effect" is "to bring about the substantive evil which the legislative body might prevent."

Even worse for Brandenburg, the Court unanimously upheld California's criminal syndicalism statute, which was similar to Ohio's, in 1927. It "is not open to question," the justices said in Whitney v. California, that "a State in the exercise of its police power may punish those who abuse this freedom [of speech] by utterances inimical to the public welfare, tending to incite to crime, disturb the public peace, or endanger the foundations of organized government and threaten its overthrow by unlawful means."

In a concurring opinion joined by Holmes, Justice Louis Brandeis explicitly invoked the "clear and present danger" test. "To support a finding of clear and present danger," he said, "it must be shown either that immediate serious violence was to be expected or was advocated, or that the past conduct furnished reason to believe that such advocacy was then contemplated."

Despite those ominous precedents, the Court in Brandenburg unanimously agreed with Brown that Ohio's criminal syndicalism law went too far. "Whitney has been thoroughly discredited by later decisions," said the unsigned opinion, which was published in June 1969. "These later decisions have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action."

It is debatable whether those decisions actually established that principle. In the 1961 case Noto v. United States, for example, the Court said "the mere abstract teaching" of "the moral propriety or even moral necessity for a resort to force and violence" is "not the same as preparing a group for violent action and steeling it to such action." That decision overturned a Communist's conviction under the federal Smith Act, which made it a crime to join an organization that advocates forcibly "overthrowing or destroying the government." The Court had previously upheld Smith Act prosecutions of Communists in the 1951 case Dennis v. United States, citing the "clear and present danger" doctrine. But in Noto, it concluded that the prosecution had failed to prove that the Communist Party "presently advocated violent overthrow of the Government now or in the future."

Brandenburg went further by requiring a threat of "imminent lawless action" that is both deliberately incited and likely to happen. Ohio's law swept much more broadly than that. "We are here confronted with a statute which, by its own words and as applied, purports to punish mere advocacy and to forbid, on pain of criminal punishment, assembly with others merely to advocate the described type of action," the Court said. "Such a statute falls within the condemnation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The contrary teaching of Whitney v. California cannot be supported, and that decision is therefore overruled."

The majority did not explicitly renounce the "clear and present danger" doctrine. But in a concurring opinion, Justice William O. Douglas said that test was so malleable that it should be ditched for good. "I see no place in the regime of the First Amendment for any 'clear and present danger' test," he wrote, "whether strict and tight as some would make it, or free-wheeling as the Court in Dennis rephrased it." Justice Hugo Black agreed that "the 'clear and present danger' doctrine should have no place in the interpretation of the First Amendment."

The Court's First Amendment decisions since Brandenburg have validated that position. "In the more than half century since 1969," law professors JoAnne Sweeny and Eric T. Kasper note, "the Court has remained true" to the Brandenburg standard, eschewing "all iterations of the clear and present danger test."

'We Won't Have a Country'

When Donald Trump addressed his supporters at a "Save America" rally in Washington, D.C., on the day that Congress was scheduled to ratify Joe Biden's victory in the 2020 presidential election, the audience was much bigger than the one Brandenburg was able to muster on that farm in Ohio. The House select committee that investigated the ensuing riot at the U.S. Capitol estimated that 53,000 people gathered at the Ellipse to hear Trump rail against a supposedly stolen election.

Trump's remarks, which lasted more than an hour, were much longer than Brandenburg's 127-word speech at the burning cross. But while the question of whether Brandenburg advocated illegal conduct depends on how you interpret "revengeance" (which Brown described as "a word of his own coining"), Trump's speech, on its face, did not recommend violence. "I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard," he famously said.

Still, Trump's remarks were full of dark warnings about what would happen if the alleged usurper were allowed to take office. "We won't have a country if it happens," he said. "We're going to have somebody in there that should not be in there, and our country will be destroyed, and we're not going to stand for that….If you don't fight like hell, you're not going to have a country anymore."

Trump condemned the "radical-left Democrats" who, abetted by "the fake news media" and "weak Republicans," supposedly had "rigged an election." He promised that he would not surrender to their alleged chicanery: "We will never give up. We will never concede. It doesn't happen. You don't concede. Our country has had enough. We will not take it anymore….We will stop the steal."

How did Trump propose to do that? "It is up to Congress to confront this egregious assault on our democracy," he said. "We're going to walk down to the Capitol…and we're going to cheer on our brave senators and congressmen and women. And we're probably not going to be cheering so much for some of them. Because you'll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength, and you have to be strong."

It was predictable that at least some of Trump's supporters, ginned up by the phony grievance he had been pressing for two months, would try to "show strength" in ways that went beyond the peaceful protest that he described. Since that is in fact what happened, it seems safe to say that Trump's speech was "likely" to incite "imminent lawless action." Whether it was "directed" at that result seems more doubtful.

Although it may be hard to remember given the comeback that culminated in his election to a second term four years later, the immediate results of the Capitol riot were not at all favorable to Trump. His public approval rating fell sharply, and a Pew Research Center survey found that 75 percent of Americans, including 52 percent of Republicans, thought he bore at least "some" responsibility for the riot. Trump faced a second impeachment and harsh criticism from fellow Republicans who were disgusted by his reckless rhetoric, the violence and vandalism that followed, and his reluctance to intervene after the riot started. For a while, it seemed like this was the end of Trump's political career.

Maybe Trump foresaw that it would all blow over, that bitter critics would transform into toadies as he reclaimed his dominance of the Republican Party. But it seems more likely, given Trump's impulsiveness, narcissism, and irresponsibility, that he simply did not consider the potential consequences of his conduct. His recklessness was reprehensible, but that does not mean he intentionally caused a riot.

Immediately after the invasion of the Capitol, there was speculation that Trump might face federal criminal charges based on his Ellipse speech—a possibility that Michael Sherwin, acting U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, pointedly did not rule out. But the relevant statute, which makes "urging or instigating other persons to riot" a felony, expressly does not apply to "advocacy of ideas" or "expression of belief" unless the speaker urges "acts of violence" or asserts "the rightness of" or "the right to commit" such acts. Trump did neither.

The January 2021 article of impeachment against Trump charged him with "incitement of insurrection," based largely on his preriot speech. But the resolution did not allege a violation of any specific criminal statute, and no such claim is required for impeachment. Although the January 6 committee recommended several criminal charges against Trump, they were based on conduct that extended beyond the Ellipse speech, and they did not include incitement to riot. The same was true of the charges that Special Counsel Jack Smith later pursued based on Trump's attempts to stop Biden from taking office.

Those judgments are consistent with the Brandenburg test, which by design makes it very difficult to hold speakers legally responsible for the potential or actual violence of their listeners, as the ACLU's David Cole and Ben Wizner explained in a 2023 Los Angeles Times op-ed piece. "Reasonable minds can differ on whether Trump's remarks that day crossed that line," Cole and Wizner wrote. "If the prosecutors seek to hold him accountable for the mob's actions, they would have to satisfy that demanding standard. In the context of political speech, courts should be very hesitant to hold speakers liable for the actions of others."

As of December 2024, Politico reported, Trump still faced eight civil lawsuits based on his role in provoking the Capitol riot. In December 2023, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit allowed two of those lawsuits to proceed, saying Trump had failed to show that he was shielded by presidential immunity. But the appeals court expressly did not address Trump's claim that "his alleged actions fall within the protections of the First Amendment because they did not amount to incitement of imminent lawless action."

Despite his lawyers' invocation of Brandenburg, Trump seems to have only a hazy idea of what the decision means. In August, he issued an executive order instructing Attorney General Pam Bondi to "prioritize" prosecution of "American Flag desecration." Although Trump acknowledged that the Supreme Court has repeatedly deemed flag burning a form of constitutionally protected expression, he suggested it can nevertheless be punished when it is "conducted in a manner that is likely to incite imminent lawless action."

That theory fundamentally misconstrues the Brandenburg test, which refers to "lawless action" urged by a speaker, not the potentially violent response of people offended by his message. In his eagerness to crack down on flag burners, Trump glided over Brandenburg's intent requirement, which was crucial to his own legal defense.

'He Solely Engaged in Protected Speech'

To Trump opponents eager for his comeuppance, Brandenburg may seem like a gratuitous and frustrating obstacle. Progressives who support legal restrictions on "hate speech" likewise have reason to resent Brandenburg. In 2019, for example, Richard Stengel, a journalist who served as undersecretary of state for public diplomacy and public affairs during the Obama administration, decried Brandenburg in a Washington Post essay that recommended criminal penalties for "speech that deliberately insults people based on religion, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation." But the same standard that protects demagogues and bigots also protects speakers whom progressives are apt to view more sympathetically.

During a 2016 protest in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, someone picked up a rock or a piece of concrete and hurled it at police, striking Officer John Ford in the head. Although the assailant was never identified, we know it was not Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson, who nevertheless faced a lawsuit that blamed him for creating the circumstances that led to Ford's injuries.

Brian A. Jackson, a federal judge in Louisiana, dismissed that lawsuit in 2017, saying Ford's allegations "merely demonstrate that Mckesson exercised his constitutional right to association and that he solely engaged in protected speech at the demonstration." Jackson cited the Supreme Court's 1982 ruling in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, which held that "the presence of activity protected by the First Amendment imposes restraints on the grounds that may give rise to damages liability and on the persons who may be held accountable for those damages."

That unanimous decision involved a sometimes-violent boycott of white merchants in Claiborne County, Mississippi, that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People launched in 1966. The Court's reasoning relied on Brandenburg for the principle that "mere advocacy of the use of force or violence does not remove speech from the protection of the First Amendment." The justices rejected civil liability even though boycott leader Charles Evers had endorsed violence, telling potentially uncooperative shoppers, "If we catch any of you going in any of them racist stores, we're gonna break your damn neck."

Ford did not cite any similarly inflammatory statements by Mckesson. In fact, Jackson noted, Ford conspicuously failed to explain "how Mckesson allegedly incited violence."

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit nevertheless revived Ford's lawsuit in 2019, focusing on the allegation that Mckesson "directed the demonstrators to engage in [a] criminal act" by blocking a highway, which "consequentially provoked a confrontation between the Baton Rouge police and the protesters." In 2023, after consulting with the Louisiana Supreme Court on state tort law at the instruction of the U.S. Supreme Court, the 5th Circuit reiterated its conclusion that Ford could proceed with his lawsuit.

That decision provoked a partial dissent from Judge Don Willett, who objected to the end run around the principles established by Brandenburg and Claiborne. Willett warned that the majority's "novel 'negligent protest' theory of liability" would "reduce First Amendment protections for protest leaders to a phantasm, almost incapable of real-world effect." Such a rule, he said, "would have enfeebled America's street-blocking civil rights movement, imposing ruinous financial liability against citizens for exercising core First Amendment freedoms." He cited Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1968 march in Memphis, which was marred by vandalism and a violent police response, as an example.

In April 2024, the Supreme Court declined to review the 5th Circuit's decision. But three months later, Jackson again rejected liability for Mckesson, saying Ford had failed to allege the elements for a negligence claim under Louisiana law. Jackson added that Ford's claim "fails under the First Amendment." In the 2023 case Counterman v. Colorado, he noted, the Supreme Court made it clear that "the First Amendment bars the use of 'an objective standard' like negligence for punishing speech." The Court explained that "the First Amendment precludes punishment, whether civil or criminal, unless the speaker's words were intended (not just likely) to produce imminent disorder."

Ford appealed Jackson's ruling to the 5th Circuit, where the case is pending as I write. Since the ruling in Counterman came after the 5th Circuit's 2023 decision allowing Ford's lawsuit to proceed, it's not clear how the appeals court will rule this time around. But Counterman relied on the logic of Brandenburg, and Mckesson's prospects would be notably worse if Ford had been allowed to pursue his claim that the activist "incited the violence" simply by "pumping up the crowd."

'The Trump Administration Will Not Tolerate It'

Given Trump's dim view of Black Lives Matter, we can surmise that he is not rooting for Mckesson. But the constitutional argument against civil liability for Mckesson is essentially the same as the constitutional argument against suing or prosecuting Trump for what he told his supporters before the Capitol riot. The same argument is crucial to assessing Trump's crusade against foreign students who express views he does not like.

During his 2024 campaign, Trump repeatedly promised to arrest and deport student protesters whose pro-Palestinian advocacy he viewed as antisemitic, pro-terrorist, or anti-American, even if they had not engaged in violence, vandalism, or other illegal behavior. He began delivering on that promise on March 8, 2025, when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested former Columbia University graduate student Mahmoud Khalil, a legal permanent resident, because of his role in protests against the war in Gaza.

To justify Khalil's deportation, the administration invoked a provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act that authorizes the removal of noncitizens when the secretary of state determines that their "beliefs, statements, or associations," although "lawful," threaten to "compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest." In a two-page memo, Secretary of State Marco Rubio claimed Khalil had participated in "antisemitic protests" that "foster[ed] a hostile environment for Jewish students." Those activities, Rubio averred, "undermine[d] U.S. policy to combat anti-Semitism around the world and in the United States."

After Khalil's arrest, Trump described him as "a Radical Foreign Pro-Hamas Student" and promised "this is the first arrest of many to come." There are "more students" at "Universities Across the Country" who "have engaged in pro-terrorist, anti-Semitic, anti-American activity, and the Trump Administration will not tolerate it," he said. "We will find, apprehend, and deport these terrorist sympathizers from the country."

ICE subsequently arrested other students and scholars who allegedly fit that description, including Tufts University graduate student Rümeysa Öztürk, whose only offense seems to have been co-authoring a Tufts Daily op-ed piece supporting the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement. In each case, the government argued that the arrestee's pro-Palestinian advocacy amounted to antisemitism, rhetorical support for Hamas, or both.

The detainees disputed those characterizations. Yet even if they were accurate, the speech at issue would still be constitutionally protected under the Brandenburg test.

The government's lawyers obscured that point by citing Harisiades v. Shaughnessy, a 1952 Supreme Court decision that upheld deportations based on Communist Party membership. That ruling hinged on the government-friendly "clear and present danger" test that the Court later repudiated.

Writing for the majority in Harisiades, Justice Robert H. Jackson rejected the idea that, "in joining an organization advocating overthrow of government by force and violence, the alien has merely exercised freedoms of speech, press and assembly which [the First] Amendment guarantees to him." Not so, Jackson said, citing the Court's 1951 decision in Dennis, which held that even U.S. citizens could be criminally punished under the Smith Act for joining the Communist Party.

"In this case we are squarely presented with the application of the 'clear and present danger' test, and must decide what that phrase imports," Chief Justice Fred Vinson wrote in the Dennis plurality opinion. "Overthrow of the Government by force and violence is certainly a substantial enough interest for the Government to limit speech….If Government is aware that a group aiming at its overthrow is attempting to indoctrinate its members and to commit them to a course whereby they will strike when the leaders feel the circumstances permit, action by the Government is required."

Under Brandenburg, by contrast, such advocacy can be punished only if it is both intended and likely to result in "imminent lawless action." When you combine the Brandenburg test with the Supreme Court's 1945 decision in Bridges v. Wixon, which recognized that "freedom of speech and of press is accorded aliens residing in this country," the First Amendment case against Trump's speech-based deportation policy looks a lot stronger than the government's lawyers suggested.

In a brief opposing a First Amendment lawsuit against what the plaintiffs called Trump's "ideological deportation policy," Justice Department officials acknowledged Bridges, which they said did not show that the First Amendment applies "in full" to alien residents. They backed up that point by citing Harisiades. But they did not mention Brandenburg at all, presumably because it would have undermined their argument.

Brandenburg is undeniably inconvenient for people who think speech that offends them should be punished. But those very same people may find refuge in Brandenburg when their own speech provokes outrage. If you reject Brandenburg when it protects your enemies, you do so at your own peril.