Terence McKenna, the Would-Be Jesus of Psychedelics

A new biography explores the life and ideas of the man who founded the first primitive religion of the future.

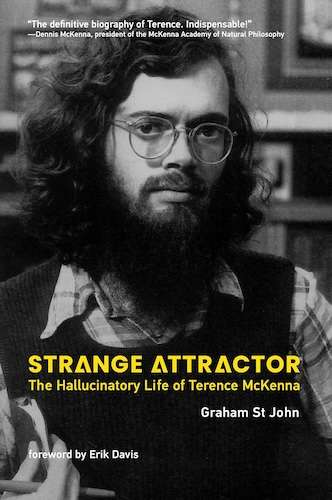

Strange Attractor: The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna, by Graham St. John, The MIT Press, 548 pages, $35

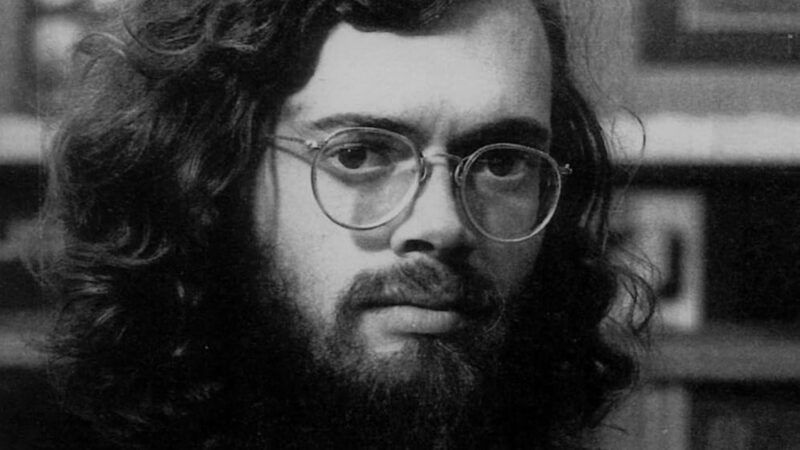

A large crowd filled the Scottish Rite Temple in downtown Los Angeles to hear the man who first synthesized LSD speak. It was October 2, 1988. The bill for the evening—"Albert Hofmann in America: Celebrating 50 Years of Consciousness Research"—was stacked: Alongside the grandaddy of LSD were such psychedelic celebrities as Laura Huxley, John Lilly, Stanley Krippner, and Andrew Weil. Hunter S. Thompson and Timothy Leary were both in the building. The master of ceremonies, introducing Hofmann with a rallying cry for a new era of psychedelic research, was Terence McKenna, arguably the movement's most eloquent spokesman.

It was a bad time for the gurus. Leary was taking gigs for as little as $1,500 (chitchat at an acid-themed art show). Alan Watts managed to drink himself to death before he made it into his sixties. Lilly's "research" into ketamine almost got him killed twice. MDMA had just been outlawed. Some of the old revolutionaries had no retirement plan short of utopia. John Lennon was dead. Huey P. Newton would soon be dead too. Eldridge Cleaver was a conservative Christian. Jerry Garcia was on heroin. Earth was a bummer.

"It's time for a revisioning regarding human potential," McKenna told a rapt audience. He compared LSD to the discovery of the telescope and Hofmann to Carl Jung and Paracelsus. Psychology without psychedelics, he proclaimed, was just "pissing into the wind."

In the early 2000s, before YouTube became a sprawling repository of his recorded lectures (over 250), DVDs of McKenna's legendary raps could be obtained from a mail-order catalogue called Sound Photosynthesis. In my early 20s, I watched in awe as McKenna weaved a dizzying array of ideas into what seemed like genuine prophecy. As far as I was concerned, these were the oracular utterances of a modern-day seer. Humanity's survival, I came to believe, was a matter of two things: spreading the use of psychedelics as far as humanly possible, and broadcasting McKenna's message across the entire planet.

Over the next two decades, as I became more familiar with McKenna's source material (Aldous Huxley, Carl Jung, Gordon Wasson, Mircea Eliade, and Marshall McLuhan, primarily), I began to suspect that things were more complicated. As the historian Graham St. John illustrates in Strange Attractor, his delightful new biography of the man, McKenna was a "master bullshitter."

Chronicling McKenna's ascendancy to Hofmann's opening act, St. John's narrative zigzags through India, Nepal, South America, Mexico, Israel, and Canada. The aspiring writer was once a fugitive, wanted in the United States for drug trafficking. (His little brother, Dennis, we learn, ratted him out!) Under the guise of an eccentric butterfly collector and antiquities trader, McKenna stuffed pounds of golden Lebanese hash into hollowed out Ganesha statues and shipped them to friends and accomplices in California, Colorado, and New York. The proceeds were used to support his nomadic writing habit, including a discarded perennialist manifesto he later decided was "dog shit." (The titles of his two early tomes are enough to keep one from looking any further: "Crypto-Rap: Meta-Electrical Speculations on Culture" and "The Future of Magic in Electronic Societies.")

McKenna's quotes have become almost as commonplace as Rumi's, appearing everywhere from bookstore tchotchkes to the writings of the accused assassin Luigi Mangione. He is practically a saint in the psychedelic manosphere, his ideas standard fare on popular podcasts hosted by Joe Rogan and Danny Jones. St. John smartly separates his explication of McKenna's wild and often convoluted theories (mushrooms, he once told his followers, infuse the psyche with an "alien vegetation spirit from the stars") from the man's life story, which includes plenty of colorful adventures, including a spell in the Amazon jungle where he was allegedly "buzzed" by a UFO. Both parts of Strange Attractor are sometimes tedious but ultimately worth the effort for anyone interested in psychedelics and esotericism.

Born in a small town in western Colorado in 1946, McKenna began reading Aldous Huxley at age 12. The mold for his own later work was formed by Huxley's Brave New World—"the most intelligent anti-drug book ever written," in McKenna's estimation—and Jung's Psychology and Alchemy. Obsessed with primitive societies and the relationship between myth, history, and the human mind, McKenna developed an apocalyptic futurist eschatology and what he called the "archaic revival." Synthesizing a vast array of sources—none more important than James Joyce, whom McKenna saw as a kind of hyperspace prophet—his efforts were largely aimed at elevating the reputation of the shaman or witch doctor through a lucrative and wildly entertaining public relations campaign.

"That which he deemed shamanic," St. John points out, "was unlike anything in Anthropology 101." But like Mircea Eliade, a historian of religion who became one of McKenna's early heroes, McKenna was less interested in scholarship than storytelling.

"I grew up through the 1950s," McKenna once told an audience. "I can remember these movies where the white people get captured by the cannibals and put in the pot to be boiled. It was always a witch doctor, and this guy epitomized the most nightmarish forces of unbridled primitivism and ignorance imaginable. Now, this has become the guiding paradigm of the culture, because what the shaman is, is the person who is still in touch with this organic intelligence which lies behind nature." Yet his revised portrait of the witch doctor was not much more reliable than those old movies.

Searching for proof of psychedelic use in various religions, McKenna ultimately did not have the aptitude or patience to learn foreign languages, the advanced mathematics he invoked, or to spend significant time observing others in the field. He was a minstrel at heart, and his philosophy was a patchwork quilt of new transhumanist and old occultist ideas as shaped by his anarcho-libertarian political leanings. (McKenna imagined the shaman as a "true anarchist.") As his experiences with psychedelics became more intense, close friends saw him become something like a "fire and brimstone preacher." Though McKenna cultivated the persona of a Victorian plant hunter and "eccentric Florentine prince," there was more than a touch of the traveling salesman in him. Convinced of a hidden reality populated by elves and other circus-like magical creatures, he came to believe that humanity was reaching a "transitional phase" where we would be uploaded into some kind of Gaian hyperspace. He pegged the exact date of humanity's end—and new beginning—as December 21, 2012.

What are we left with? An enchanting orator with a wicked sense of humor, one who never fails to amuse and inspire. If America is truly "the only remaining primitive society," as Jean Baudrillard argued, then McKenna might have founded the first primitive religion of the future.

Optimally, the psychedelic experience allows you to explore the limits of your own humanness and what it means to be alive (paired, ideally, with some good old-fashioned fun): The sting of death is temporarily removed or at least attenuated for a time. Suboptimally, it bleeds into narcissism, a bunch of high and mighty Peeping Toms mistaking the squeaks and moans emitting from their own mental gearbox for the soft murmurs of invisible spirits—or worse, the voice of God. At a certain point, sniffing around the sacred bouquet in an attempt to detect the essential qualities or flavors of truth and ultimate reality begins to resemble a secret delight in smelling the aroma of one's own mental flatulence. In McKenna's life and work, both are displayed in spades.

Show Comments (68)