'Louisiana Lockup' Detention Center Is Punishing Immigrants for the Same Crime Twice, New Lawsuit Says

Oscar Amaya has been held in federal immigration custody for over six months after receiving a final order of removal, raising serious constitutional concerns about how long the government can detain people.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed suit on Monday, accusing Louisiana's new immigration detention center, "Louisiana Lockup," and the Trump administration of indefinitely locking up immigrant detainees in the facility and punishing immigrants for the same crime twice, in violation of the Double Jeopardy Clause.

The Louisiana facility opened on September 3, using the blueprint forged by Florida's Alligator Alcatraz. After Republican Gov. Jeff Landry declared a state of emergency in July to expedite repairs to a section of the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, Louisiana—a maximum-security prison notorious for violent and inhumane conditions—the state partnered with the Department of Homeland Security to add 416 immigrant detainee beds.

"This facility is designed to hold the worst of the worst criminal illegal aliens," and is meant "to consolidate the most violent offenders into a single deportation and holding facility," Landry said during a press conference on opening day. "Angola is the largest maximum-security prison in the country," he continued, "with 18,000 acres bordered by the Mississippi River, swamps filled with alligators, and forests filled with bears."

"If you don't think that they belong somewhere like this," Landry said, referring to the incoming immigrant detainees, "you got a problem."

But in the case of Oscar Amaya, a 34-year-old man who is currently detained at "Louisiana Lockup," there may very well be a problem. The lawsuit, filed in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana, argues that Amaya's continued detention violates the Double Jeopardy Clause and is designed to punish him—again—for a prior conviction.

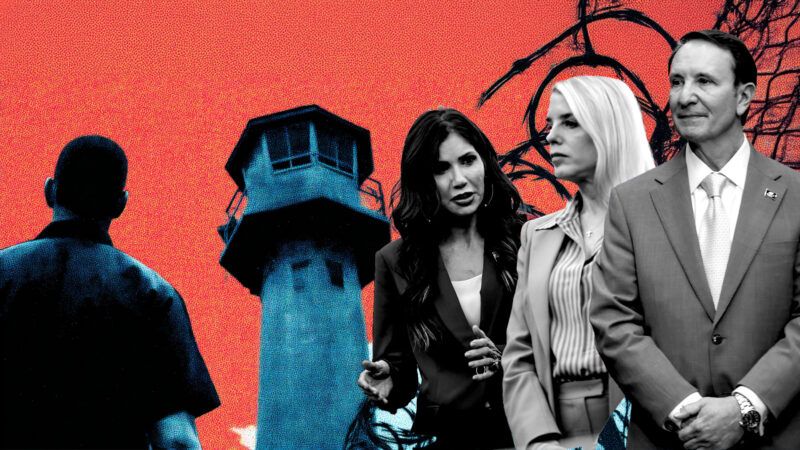

Although immigration detention is a civil penalty, double jeopardy applies if the civil sanctions are applied punitively. As the complaint, reviewed by Reason, points out, the punitive nature of imprisonment in a place like Angola is no secret. Rather, both Landry and Trump administration officials seem to relish in the facility's violent past. "This is not just a typical [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] ICE detention facility that you will see elsewhere in the country," Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem proclaimed during the facility's opening. "This is a facility that's notorious.…Angola Prison is legendary."

Amaya fled Honduran gang life in 2005 and worked in the United States "without incident" until 2016, according to the complaint. That year, he was arrested and later "convicted of attempted aggravated assault, possession of a weapon (knife) for unlawful purpose, and unlawful possession of a weapon (knife)." Amaya was sentenced to four and a half years in prison, but was released after two years with good time credits.

After serving his time, Amaya was transferred to ICE custody. Although he was initially released with an ankle monitor due to a medical condition, he was taken back into ICE custody in 2023, where he remained while fighting his removal and worsening health.

In March of this year—nine years after his initial arrest—Amaya was granted Convention Against Torture protection after demonstrating that he will be, more likely than not, tortured if deported to Honduras. However, Amaya has remained in ICE custody without any active criminal or civil offenses pending against him. After receiving a final decision on his immigration proceedings, ICE denied his release, stating that the agency "expects to receive the necessary travel documents to effectuate [Amaya's] removal," which is believed to be practicable, in the public interest, and "likely to occur in the reasonable foreseeable future."

But after six months of failed attempts to deport him to Mexico, the complaint argues, Amaya has been detained past the six-month timeline the Supreme Court deemed "presumptively reasonable" in Zadvydas v. Davis, a decision meant to prevent the "indefinite detention of aliens" that could raise "serious constitutional concerns."

His indefinite lockup because of his prior crimes is also clearly unconstitutional since he's already served the time for his original criminal conviction. "[Amaya's] liberty is of extraordinary importance to this country: if he stays behind bars indefinitely, the Constitution becomes nothing more than a house of cards," argue his attorneys.

Unfortunately, indefinite detentions like this are a feature, not a bug, of the Trump administration's immigration crackdown. "To be clear: If you commit a violent crime in this country…we are going to prosecute you here, and we are going to keep you here for the rest of your life," said Attorney General Pam Bondi at the opening press conference for "Louisiana Lockup."

Amaya's case joins a growing list of legal challenges lodged against state-run immigration detention centers popping up around the country, which are backed by $45 billion in funding from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed in July. But as the Trump administration races to add more beds to detain an unprecedented number of immigrants, questions regarding due process and constitutional rights will keep mounting—rights designed to prevent the government's abuse of power and endless legal harassment in the first place.

Show Comments (33)