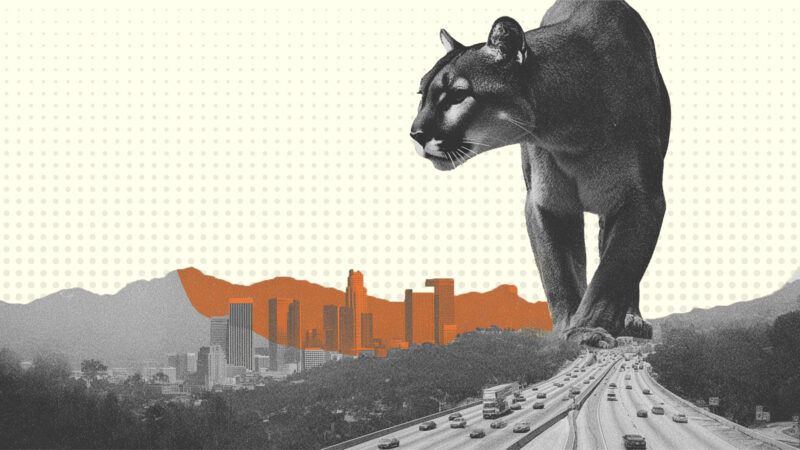

Mountain Lions in Los Angeles Don't Need a $92 Million Government Project To Survive

There are cheaper solutions to help the not-endangered beasts get around.

Los Angeles once had a four-legged folk hero: P-22, a lone mountain lion that improbably took up residence in Griffith Park. A famous photo features the charismatic cat with the Hollywood sign strategically aligned in the background. When P-22 died in 2022, the outpouring of attention included a celebration of his life at the Greek Theatre. P-22 became a rallying cry that pried loose the donations and public dollars that funded the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing across the U.S. 101 freeway near Los Angeles.

A bridge dedicated to helping animals safely cross one of the busiest freeways in the nation seems a cause worth supporting. But this particular effort comes with a breathtaking price tag and lavish overengineering—and is entirely unnecessary to protect the mountain lion.

Consider Utah's Parleys Canyon Wildlife Overpass, completed in 2018. The bridge is about 16,000 square feet, and it cost $5 million to build. That works out to roughly $312 per square foot. California's Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, meanwhile, is 35,700 square feet, with an estimated cost of $92 million—$58 million squeezed out of California taxpayers. That's more than $2,500 per square foot, over eight times the cost of the Utah bridge. California does have strict earthquake building codes and higher labor costs, but this lion-saving project is still four times the per-square-foot cost of a typical California bridge.

The project team went to extraordinary and expensive lengths to give the bridge a "natural" feel. The California Transportation Department enlisted a design team to engineer a custom soil mix "to mimic the biological makeup of the native soils around the site," as the Los Angeles Times reported in April, and has cultivated over a million seeds in an on-site nursery since 2022.

Do the animals even care? Makeda Hanson, Utah's wildlife migration coordinator, says that "animals do not spend a lot of time foraging or trying to hide on these crossing structures. They use it as a thoroughfare." If wildlife simply crosses and moves on, why devote so much time and money to creating a miniature ecosystem on the deck of a bridge?

The bridge's proponents insist it's needed to address low genetic diversity in the Santa Monica Mountains' mountain lion population. The 101 freeway limits animal movement between the Santa Ana Mountains and the Santa Monica Mountains. PBS reported in 2019 that Southern California "mountain lion populations are at risk of becoming extinct in as little as 50 years."

That claim traces back to a 2019 study by John F. Benson and others, which estimated a 16–21 percent probability of local extinction within 50 years. The same paper said that importing just one mountain lion from another region every two years could reduce that probability to 2.4 percent.

That solution is far cheaper than building a $92 million bridge. A peer-reviewed 2014 paper in PLOS ONE found that translocating similarly sized big cats—cheetahs and leopards—would have median costs of $2,760 and $2,108, respectively. Even rounding up to $3,000 per move, $92 million could fund more than 30,000 years of biannual mountain lion translocations. Considering an average bridge lifespan of about 100 years, moving the animals is far more cost-effective approach to preservation than the bridge.

Bridge proponents see the Santa Monica Mountains' mountain lions as a population on the brink. But a stable, self-sustaining number of lions already live in the range, and the bridge will not significantly increase that number.

According to the Benson study, their "main study population in the [Santa Monica Mountains] is very small," with an "estimated maximum of 15 individuals." This number isn't low because of recent die-offs or poor reproduction; it reflects the fact that the habitat simply can't support more. Mountain lions are solitary, territorial predators. As Benson's paper notes, you'll generally find just one or two breeding adult male mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains at any given time.

"Territoriality and intraspecific strife," the authors explain, "appear to interact with space limitation and anthropogenic barriers to increase mortality risk." In other words, even if new lions arrive via a wildlife crossing, they will have to compete for limited territory. That competition often ends in one lion killing another.

The mountain lion population is not low because of a freeway. The number of lions in the Santa Monica Mountains is capped by the natural carrying capacity of the area. Building a $90 million–plus bridge won't change that ecological reality.

And besides, mountain lions are not endangered. The International Fund for Animal Welfare has seven different classifications of how endangered an animal is, with "least concern" being at the bottom of the list. And according to the Mountain Lion Foundation, that's their official conservation status. Mountain lions are one of the most widely distributed mammals on the planet, with a range that stretches from Alaska to Argentina.

Even in the Santa Monica Mountains, right where this bridge is being built, the National Park Service says the population is "stable, with healthy rates of survival and reproduction." The lions were managing to cross U.S 101 even without the bridge. The Liberty Canyon underpass has multiple culvert pipes that wildlife can easily access and has been used successfully for years. One tracked lion, P-64, crossed the 101 and 118 freeways more than 40 times using them.

Liberty Canyon underpasses work, and for far less money. Matt Howard, a natural resources manager with the Utah Transportation Department, explains that "there's some data showing that mule deer prefer underpasses and that animals like pronghorn, elk, and moose prefer overpasses. But…it doesn't mean that one crossing won't [allow the animals to cross]. It just means it takes a little longer for them to use it."

Animals adapt. An underpass might take longer to become heavily used, but it still does the job, without requiring $92 million and years of construction.

Conservation efforts should be guided by need, efficiency, and measurable impact, not by whether a project makes for a good press release. The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is widely overpriced, unnecessarily complex, and redundant.

Show Comments (41)